Eat, Love, Sculpt

SHE COULD BE described as an Italian Elizabeth Gilbert travelling to India, chisel in hand, on a voyage of self-discovery. What makes Simona Bocchi different is that she’s an Italian and a sculptor.

To underline how different, we might be forgiven for taking a detour to the recent excavations that have been taking place at Pompeii, the once prosperous town near Naples that was destroyed in a volcanic eruption in 79 AD from the still active Mt Vesuvius. One of the astonishing statues to have been unearthed is that of the Greek god Priapus. He stands naked displaying in graphic detail his male member extended in what can only be described as epic proportions.

We can only marvel at the long tradition of civilised discourse that created such extraordinary masterpieces 2,000 years ago.

These are traits that allow Bocchi to travel across timeframes and cultures with a bracing self-confidence that gives her observations a certain charm, even as they are tinged with an interloper’s arrogance seeking redemption in the mysterious East. Her search is different in other ways. She’s already trained as a sculptor amongst the best ateliers, teachers and schools in Italy and in England. Bocchi has the body and physical attributes to have walked the ramp as a model while studying to be a sculptor. Her friends tell her that she has a spirit, or daemon, that carries her forward in inexplicable ways.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

She has confronted a block of pure Carrara marble, the finest white marble in the world. She has created a vision of a horse, inspired by the untamed horses that she’s been privileged enough to ride bareback. Yet, in one of her moments of inexplicable passion, after she’s carved her first horse head with flaming mane and nostrils, she’s decided to set it free by taking a hammer and hacking it into a mountain of rubble.

In short, the energy that she displays could be described as ‘Priapic’; the god who is not only designated as a fertility symbol for obvious reasons, but also one associated with plants, gardens and live-stock, perhaps even horses, though that’s just an aside. In Bocchi’s vision of herself, these attributes take on what she insists is a sensitivity towards Nature, or an ability to be aware of the aura and essence of fellow human beings.

This is of course as may be. Those who dabble in such esoterica and have followed, or at least heard of, the Russian mystic Gurdjieff, Osho the permanent sage of expanded consciousness, and sought inspiration at the now abandoned shrines, where the Beatles once worshipped, or where the Buddha may have preached, will be thrilled to hear of Bocchi’s own second-hand reports from some of these experiences. There’s also an exchange of meaningful smiles with the Dalai Lama.

Of these, perhaps the most erotic is a brief encounter towards the end when Bocchi travelling by train and ensconced on a second-tier sleeper with a Rajasthani man with a chiseled mouth, helps to initiate him into the art of love. Like the marble horse, he is soon discarded; but whether bruised permanently or not, she tells us that he survives the embrace of the Italian.

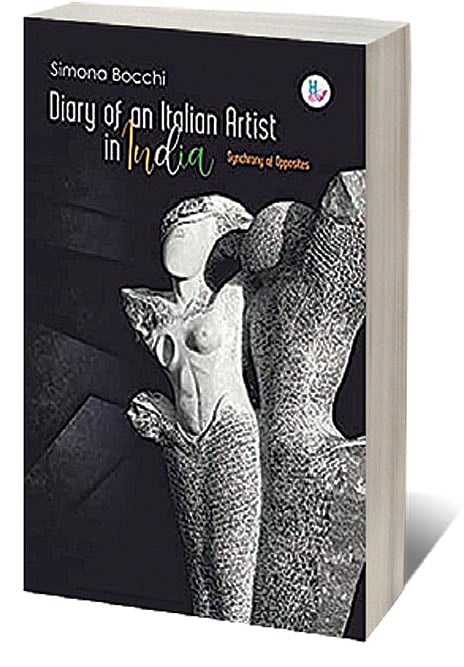

None of this should detract from the main purpose of the diary. It’s a record of her struggles as a sculptor of rare energy and implacable strength. The cover shows one of her visionary Indian creations—a Shiva-Parvati. As she describes the conjoined figures, abstract and yet vibrant. “It was monumental, but also elegant, it blended the elements of a spirit who was both male and female. It was born out of one form as monolith that took on the characteristics that defined it.”

Like the chisel marks, the text translated from the Italian by Neil Maroni is full of slips and spelling errors, but when confronted with the divine, who are we to complain?