Call of the Spirits

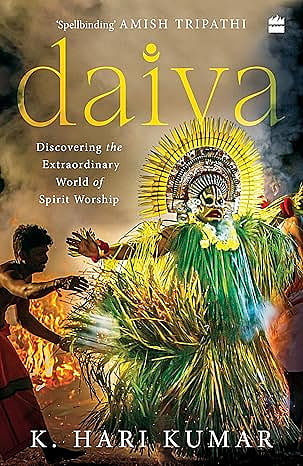

Daiva is the personal journey of author K Hari Kumar in search of his cultural roots and his ‘Satyolu’ (spirit deity) in Tulu Nadu, comprising Dakshina Kannada, Udupi and Kasargod in coastal Karnataka. Tulu is a Dravidian language that was little known outside of the South until the popular Kannada movie Kantara hit the screens. Tulu has a distinctive tradition of oral folktales or paaddanas that are a part of kola, a ritualistic dance used to summon powerful spirit deities or bhutas who protect the land. They were wrongly identified as ghosts in an early English work titled The Devil Worship of the Tuluvas. ‘Bhu’ means earth and ‘bhuta’ means ‘given by the earth,’ which shows that this ancient tradition of spirits who protect is rooted in the region.

The author starts with a discussion on ‘Divination, Spirit Possession and Spirit Dance Forms.’ While he is not challenging rationalism, such traditions have bound people who live far away but come together annually to witness the kola. There are several spirits: daivas (not devas), spirits who have originated from a divine or natural source; naagas, serpent deities who inhabit the naagabana (serpent groves, known as sarpa kaavu in Kerala) and ensure fertility and well-being; and Bermer, a moustachioed warrior resembling Ayyappa. The spirit deities include totemic spirits such as Panjurli the boar, Mahisha the buffalo, and puranic spirits such as Vishnumurthy embodying Narasimha.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

A sthaana is constructed in every village for the kola and the items pertaining to the kola are preserved either in the house or in the sthaana. The artists belonging to the Pambada, Parava and Nalike communities, reside in the vicinity of the sthaanas and observe strict regulations on food and drink. The author describes the important aspects of the ritual: the banana plant, areca nut and flowers. He describes the purification of the land, pre-ritual preparations, and the transformation of the artist into the daiva (complete with sacred anklets, skirts made of areca leaf sheaths and coconut palm fronds, a headdress, and with elaborate face painting) as in Theyyam or Kathakali. The music revs up till the dancer is ‘possessed’ by the daiva and speaks to the medium. The daiva solves disputes, suggests reliefs and settlements and dispenses a sort of justice. Omens and misfortune are linked to one’s neglect of the moola naaga or family deity, a tradition common across South India where the family deity must be regularly propitiated to prevent mishaps. The solution offered by the spirit medium has a psychological impact, says the author, “offering a sense of hope, control, comfort, community and closure.” Its effectiveness would depend on the individual.

The second part of the book has fascinating stories of spirit deities like Satyamma Kallurti and Beera Kalkuda; Panjurli the boar deity made famous by Kantara; Koti and Chennaya, warrior brothers; Pilichandi, the tiger/leopard deity; Manthradevathe of Kerala, and other royal and fearsome characters like Veerabhadra who became spirits due to various events in their lives. This forms part of the treasure house of Indian folklore, with close connections to the ‘other’ world of spirits.

The practice of venerating spirit deities is found in many parts of southern India, especially Kerala which shares several similarities with Tulu Nadu. Followers of daiva or spirit worship regard daivas and bhutas as satya or the truth. While much of this practice has merged into a larger organised religion, the continued belief in spirit deities proves their continued importance in this region.

This book is a fascinating encounter with another aspect of faith, the belief in, and the invoking of spirits to solve earthly problems. It is slowly disappearing elsewhere as the construction of large temples to popular deities takes precedence. But it is comforting to know that there is still a part of our country where ancient traditions not only linger but are practiced as before.

A glossary of Tulu words and names of spirits is an essential addition to the next edition. Also, Tulu once had a script: there is an inscription identified as Tulu in the Government Museum, Chennai, not the Grantha-based Tigalari script now used.