Between Pre-modern and Modern Times

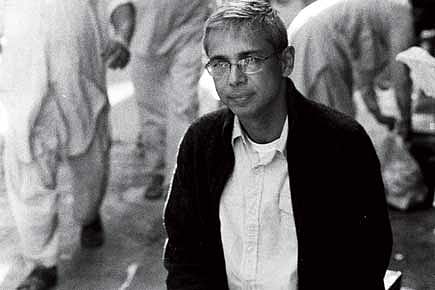

The adventures of Musharraf Ali Farooqi, who quit his job as a journalist in Pakistan to work in a packaging factory in Toronto

The early nineties were a terrible time to be living in the Subcontinent. Kashmir was torn asunder by militancy and counter-insurgency, and riots and bombs killed thousands in Bombay and large swathes of north India. Across the border, in Pakistan's largest and most interesting city, Karachi, ethnic violence between Mohajirs led by Mohajir Qaumi Movement (MQM) and various ethnic and political groups of Karachi was intense. Between 1992 and1994, the Pakistani military launched a brutal crackdown, 'Operation Clean Up', which largely targeted the MQM. Between 1994 and 1995, around 5,000 people were killed in Karachi, according to the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan. "It was a time when bodies would be found in sacks on the streets of the city," novelist and translator Musharraf Ali Farooqi, who was working as a journalist at The News newspaper in Karachi in 1994, told me.

Farooqi's parents migrated from north India to Karachi in 1947. He had dropped out of an engineering college to pursue reading and writing. One of his first literary attempts was a parody he wrote to impress the foremost satirist of Pakistan, Mohammad Khalid Akhtar. "He liked it," Farooqi smiles in reminiscence. As his city was being ruined, Farooqi steeled himself to follow his passion, and founded an English language literary magazine, Cipher. "We were thinking of a quarterly." Cipher had some short stories, a spoof on Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, an essay imagining the secret history of the flying carpet, and some poems.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Farooqi didn't want to make politics the subject of his writing. "I was interested in human relationships and fantasy," he said, "I wasn't going to change what I wanted to write because MQM had been formed." He never reads political books. "I follow politics. I read the newspaper and make my decisions for the day: is it safe to step out? Do I need to store water and milk?" Yet, violent politics was to impinge on the graph of his life. Cipher lasted two issues. A co-founder emigrated to Australia. Farooqi was married to Michelle, an artist, who came from a Christian family. "Everything was so uncertain those days," he says. They migrated to Canada.

The Farooqis knew the New World wouldn't be easy. Having dropped out of an engineering school, he didn't have a basic degree that could earn him a place in the knowledge economy. They prepared to barter the professional security of journalistic life in Karachi with odd jobs in peaceful Toronto. Musharraf and Michelle began their new life as workers on the assembly line of a packaging factory, filling boxes with styrofoam pellets, day after day of toil. Then Farooqi moved from the factory to the kitchen, working at Taco Bell, Pizza Hut, and Harvey's Burgers—the Canadian McDonald's. Four years later, in 1999, he became a Canadian citizen; his work situation improved marginally. His shift was from 8 in the morning to 5 pm. After a tiring day, Farooqi would head home or to the Toronto University library and read the classics. The library was well stocked with classics of Urdu literature, and Farooqi immersed himself in high literature in Urdu and English. Charles Dickens was his favourite. "I read everything Dickens wrote."

One winter evening, the metro in Toronto shut down. Farooqi had left the fast-food kitchen and was wandering the streets, hoping to find a way to get home. He walked into a coffee shop to kill time. "The music in the café was very good," he said, "When I returned home, my memories were that of the café and music, not the kitchen." The café became a buffer between the kitchen and the desk. He returned home fresher and wrote at night—working on several stories and novels.

In 1998, Farooqi found a translation of some pages of the great Indo-Islamic epic, Dastan-e Amir Hamza or 'The Adventures of Amir Hamza'. A sample of this translation by an American university professor left him bewildered, disappointed. Farooqi had no formal training in translation, but had been translating the poems of his friend and one of the foremost contemporary Urdu poets, Afzal Ahmad Syed. He ordered a microfilm of Dastan-e Amir Hamza from the British Library. The epic of Amir Hamza, which describes the magical, action-filled adventures of Amir Hamza, an uncle of Prophet Muhammad, has its origin in the oral tradition of Arabia and medieval Iran. It follows the campaigns of Hamza in service of Naushervan, the Persian emperor who worships fire and whose half-Chinese daughter, Mehr-Nigar, Hamza pines for. Aided by a trickster, Amar Ayyar, Hamza battles, among others, an evil giant, Zamarrud Shah, who features as his arch enemy. Apart from its fantastical tales, demons, flying objects, dragons and fairies, what is striking about this medieval Muslim epic is its irreverence towards religion and orthodox clergies.

It was immensely popular from Iran to Turkey to Malaysia, Indonesia and Mughal India, where dastangos (storytellers) would perform it on the steps of Jama Masjid in Delhi, in the bazaar of storytellers in Peshawar, and at the Mughal court. In India, it gained new elements, characters, sub-plots. Ghalib, the great poet, was enthralled by the Dastan-e Amir Hamza and hosted performances at his house. Its biggest supporter, however, was Emperor Akbar, who commissioned an illustrated version of the epic, which took 14 years, and, apart from the text, included 1,400 full pages of Mughal miniatures.

The epic was published in an Urdu edition in 1855 by Ghalib Lakhnavi and revised by Abdullah Bilgrami in 1871. A more exhaustive version came out in 1917 from the famed Naval Kishore Press in Lucknow: 46 volumes of around a thousand pages each. The microfilm that Farooqi received from the British library was the 1871 version compiled by Abdullah Bilgrami. "It took me a few months to translate the first 20 pages. Its Urdu was heavily Persianised, but slowly I found a rhythm." How would this sound in English? Farooqi continued to ask himself as he laboured in the evenings. Seven years later, he had an almost thousand page translation. He had found a literary agent, who sent it to an editor at the prestigious Modern Library. In 2007, The Adventures of Amir Hamza was published to great acclaim; its raving New York Times review was titled, 'Eat Your Heart Out, Homer!'

He followed that up with a more ambitious translation project, aiming to translate a 19th-century Urdu dastan writer from Lucknow, Muhammad Hussain Jah's magisterial fantasy, Tilism-e-Hoshruba, which again features Amir Hamza and Amar Ayyar fighting the good fight against arch-evil Afrasiyaab. He set up his own publishing house, Urdu Project, and published the first volume of Tilism, but had to stop for want of funding. "It will take me eight more years. I have to translate 23 more volumes of Tilism," Farooqi told me.

His enviable, single-minded devotion to literature continued. Farooqi completed work on a Jane Austenesque novel of social mores set in Karachi, The Story of a Widow, published in 2009. The novel's protagonist, Mona, is a widow living in a genteel Karachi neighbourhood, a watchful portrait of her husband hanging in her living room. A mysterious widower, Salamat Ali, moves in as a tenant next door. Mona is attracted to him, but has to restrain herself. Farooqi describes the non-verbal communication, watchful of matters of propriety in masterly detail. Salamat sends a proposal for marriage, and Farooqi builds up the great joint family drama with finesse, leading to their eventual marriage and its own dramatic rites of passage.

Around the same time, his homeland Pakistan was going through some of its most troubled times: the war in Afghanistan, terrorist strikes throughout the cities of Pakistan, 20-hour power cuts, and long lines outside immigration counters. "My father was unwell, and because of his condition we could not stay in Canada," says Farooqi. He moved back to Pakistan, where they live in a middle-class area of Karachi. His relationship with politics remained unchanged. He still read the newspapers to check whether it was safe to step out, and ignored the plethora of Af-Pak books. There, he also reworked the draft of a new novel.

Between Clay and Dust, published this April in India, is a haunting meditation on a man's fanatical attachment to his art, status and power, and its fallout on his relationships. Set in an unnamed city which could be either Lucknow or Karachi, the book follows the fortunes of Ustad Ramzi, the greatest wrestler of the land, who is fanatically devoted to the purity of his art and honour of his clan. It plays out through the Ustad's difficult relationship with his younger brother Tamami, callous in his duties as a wrestler and eager to succeed his ageing brother's title, Ustad-e-Zaman. Ustad Ramzi, blinded by his self-love and puritanical attachment to the codes of wrestling—from preparing the soil of the akhara (pit) to the schedule of exercises, to the display of strength—doesn't see in Tamami a worthy successor.

As the ageing Ustad faces challenges from stronger rivals, he puts Tamami through a rigorous regime of training, whereupon a violent streak is unleashed within the younger wrestler as he becomes aware of his fatal strength. Ustad Ramzi castigates him all along for his lack of discipline and purity, eventually chasing him away into the arms of dubious promoters and drugs, while failing to recognise his own attachment to power.

Farooqi's evocation of the relationship between the two brothers is heartbreakingly beautiful and cinematic. When Tamami, excommunicated by Ustad Ramzi from the akhara and their home and wasting on drugs, is about to fight his last wrestling match, he turns restless for his brother's presence, insisting on delaying the fight till the Ustad arrives, his eyes turning to an empty chair, as if his lost strength would recover with the Ustad's forgiveness. The Ustad never arrives. 'Tamami's voice choked up as he spoke. He did not seem to address anyone in particular: "I will go back to the akhara if I win. I will ask for his forgiveness. He will forgive me.''' Tamami loses his fight and kills himself with a drug overdose. The Ustad is left with his title alone, yet forbids his students from burying Tamami in the ancestral graveyard, shouting, "He was expelled for desecrating the place! These grounds are hallowed! He cannot be buried here! Take him away! Take him!" Tamami is buried elsewhere; Ustad Ramzi stands rigid in his place, seeing in Tamami's death an end to further disgrace to the honour of his clan. The loneliness and sorrow that envelops the Ustad despite himself is evoked masterfully in a single, direct, and terrifying sentence, '…he had recurring dreams in which he saw his brother's dead body lying without a winding sheet at his feet.'

Ustad Ramzi's few moments of reprieve are in attending music sessions at the house of the master courtesan, Gohar Jan, who represents the other dying art in the novel. Gohar Jan also evokes the other unselfish relationship with art, allowing her brightest protégé to marry a man of means, using her influence with the authorities to save, not her kotha (courtesan's house) set for demolition, but Ustad Ramzi's ancestral graveyard imperilled by a flood. The final moments of the novel describe the broken old man, conscious of his failures, making his last bid at regaining some sense of dignity by allowing the burial of Gohar Jan, who has been refused a grave elsewhere, in the very graveyard of his ancestors that he had denied his brother. Between Clay and Dust is moving, wise, and an incisive glimpse into our souls. It is also a great movie waiting to be made.