An Unknown Indian

SOME YEARS AGO, when the journalist Neha Dixit was researching the lives of home-based workers, most of whom are women, she began to visit the many tiny factories that dot the neighbourhood of Karawal Nagar in northeast Delhi. This industrial area on the Delhi-Uttar Pradesh border is where coincidentally much of the violence in the 2020 Delhi riots took place. Dixit went undercover to explore the working conditions of these factories that exploit the labour of workers to churn out everyday products that fill our homes. Her intention was to get a job there, and to write about it in her book on the lives of these workers.

“It was foolhardy of me to think that I will get a job,” Delhi-based Dixit says today over a Zoom call. “Because even if I was undercover, and I would stay quiet the whole time [during the conversation with the contractors and owners], clearly, my privilege, my body language, it was all giving it away.” Dixit would dress plainly, as tutored by a worker who took her along, and stay quiet while the contractors and owners explained the job, but they would invariably get suspicious and Dixit would fail to land the job.

But in those visits, Dixit got a good look at many of these establishments. Most of them were illegal sweatshops, operating out of dingy basements and stuffy rooms, where the workers had little knowledge who the actual owners were or even what the components they were working on were finally assembled into. Her visits took her to factories where the job was to produce the valves of pressure cookers, another where they had to punch holes in the nets to make tea strainers, and one where they had to bubble wrap and package various types of pipes. The most startling among them was a factory where women and children shelled and packaged almonds. Since there were frequent police raids, almond factories like these operated out of tiny claustrophobic rooms with no doors. All that existed would be a small window on one side of the wall, through which workers would enter and leave, and when the raids occurred, the employers would close the windows from the outside, leaving the workers to suffocate inside.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

“That was very eye opening because these were literally rooms with no doors,” Dixit says. “Since everybody breaks the almonds and packs them, there is always so much dust. The fingers [of all the workers] were always injured and everybody had this sort of cough because they were working 12 hours or 16 hours in all that dust. It was difficult for me to be in that space for even 15-20 minutes.”

Dixit made multiple visits like this to areas such as Karawal Nagar for nearly a decade, meeting some 900 odd people in all sorts of settings, from illegal factories, homes and workspaces of home-based workers to police stations and relief camps, to gather material for her debut nonfiction book.

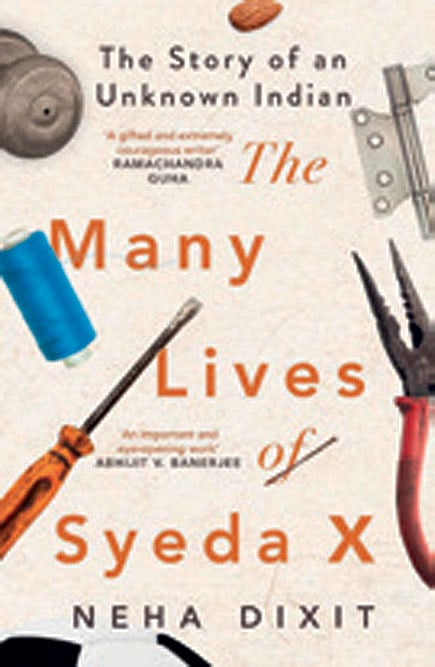

This book, The Many Lives of Syeda X (Juggernaut; 320 pages; ₹799), reported in great detail and written with empathy, tells the story of home-based workers, individuals—usually women, and often migrants from smaller towns and cities— who work out of homes and sweatshops. Jobs such as this, where payments are made on per piece rate basis, make up a large chunk of jobs for women in urban India. The wages are abysmally low and the jobs exploitative.

Dixit punctures many myths the country likes to tell about itself through this book, and brings to life the harshness and exploitative structure of the country in a way no report or statistics on the informal sector could. But the book isn’t one that limits itself to the lives of the workers alone. Dixit uses them to tell a larger story about contemporary India, bringing in its fold, the many strands—from communalism, sectarian and caste-based violence, to displacement and migration, and economic disparity—that trail life in the country today. Dixit does all this by following the life of a single person, the eponymous Syeda of the title.

Dixit had first met Syeda sometime around 2014, when she was researching an almond workers’ strike, which Syeda had participated in, that had taken place in Karawal Nagar in 2009. “This was a huge strike, and it was important because nobody had heard of a strike by home-based workers before that,” Dixit says. Home-based work had only recently been recognised— through the 2008 Unorganised Workers’ Social Security Act— and the strike for better wages and working conditions had brought the international almond processing supply chain, Dixit writes in the book, to a halt and led to almond rates going up by almost 40 percent globally. Dixit herself had quit her job at a TV channel only a few years prior, disillusioned with the media’s insistence on covering only the rich, and had begun to work as an independent journalist.

At first Syeda was hesitant to speak about her life. “When I told her I want to understand the work that you do, she agreed. This made sense to her. And later, when I started talking about her life, she would ask, ‘Arey, what is there to know’.” But over the next nine years, as Dixit kept returning to Syeda and others, trust was built and stories were shared.

Syeda is a fascinating subject around which to build this narrative. A Muslim woman from Banaras, she and her family get uprooted in the riots that take place after the Babri Masjid demolition. She and her family move to Delhi, and bit by bit, which Dixit reports in great detail, turn from a skilled workforce weaving exquisite Banarasi saris for generations to one of Delhi’s many faceless migrant workers pulling handcarts and creating knick-knacks. Dixit estimates that Syeda has held over 50 jobs in almost 30 years, often juggling many of them in a single day, from trimming loose threads of jeans, cooking namkeen, to making photo frames, doorknobs, incense sticks made of cow urine, and many more. Interestingly, Dixit names each chapter after an item Syeda is creating. Bringing in the multiple tragedies that visit Syeda and her family—including the death of one son, and another having to flee because he has fallen in love with the sister of a local gau-rakshak—Dixit paints a larger story of what it means to be a Muslim from an underprivileged background in India today. The family eventually must flee once more when the Delhi riots take place.

There are also other fascinating characters Syeda encounters. One of these is an individual named Iftekaar, who after coming into some money and land, comes up with the bright idea of selling small plots of land to migrant labourers in Sabhapur in Delhi. This earns him the wrath of local Gujjars and Brahmins, leading to his murder. Another is Nisha ‘Radiowali’, a single woman with an unconventional lifestyle, who earns her name

for making radio transmitters, and who in 2004, when electronic

voting machines were first deployed in the general elections, was hired to hack them. Yet another is Babloo, who runs a string of illegal factories, in one of which Syeda finds employment at one point. Babloo gets arrested frequently, and every time he returns, he gives Syeda a raise for taking care of the establishment without him. When he returns after his third arrest, it finally occurs to Syeda to ask him how many factories he owns. “You still don’t get it,” he tells her. “I am the owner only on paper.” He is an employee like her, it turns out, his job is to serve jail time to protect the actual owners, when a raid or closure takes place. The book also astutely depicts how political rhetoric percolates down to the masses. One such depiction is of local youths—individuals who go to school with Syeda’s children— who over time form a cow protection vigilante group that later, as the bogey of love jihad is raised, morph into a group determined to stop inter-faith marriages.

This world however is a hellish landscape, where some children consume Iodex toast, plastering their bread slices with the anti-inflammatory balm to get a high and to be more productive in the sweatshops, and where humiliations and insults are heaped daily. After every few pages, a new subsection in the book starts with some landmark moment that has just taken place. These events—from the opening up of the Indian economy in 1991, to the passing of the Right to Education Act in 2009 to the launch of India’s first space observatory AstroSat in 2015—may symbolise an achievement in recent Indian history, but here on these pages depicting such deprivation and exploitation, they ring hollow.

When the Delhi riots had just taken place, Dixit herself was also increasingly coming under threat for her articles. Dixit reported the threatening calls to the police, but nothing came out of it. One particularly frightening incident took place when someone tried to break into her house one night. When Dixit told Syeda, Syeda said, “Kutta bhaunkta rehta hai. Haathi apni chaal chalta rehta hai. (A dog will bark, but the elephant will keep following its path.)” “Her response not only underlined my privilege and the luxury of dwelling on my fear but also her ceaseless use of hope as a tool of resistance,” Dixit writes in the book.

The book ends on a somewhat hopeful note. Syeda and her husband Akmal try to rebuild their lives in a new locality in Delhi, with her daughter, Reshma, a capable young woman, along with her husband living nearby. “They are doing okay now,” Dixit says. “Although Akmal is on a bender again and has lost his job. Shazeb [Syeda’s son who had to flee after marrying a Hindu girl] has not returned either, although he keeps in touch. But Syeda is working, and so is Reshma and GG [Reshma’s husband Ghazali],” Dixit says. Life may not be looking up. But, mercifully, it is not looking down either.