Agyeya: Being Human

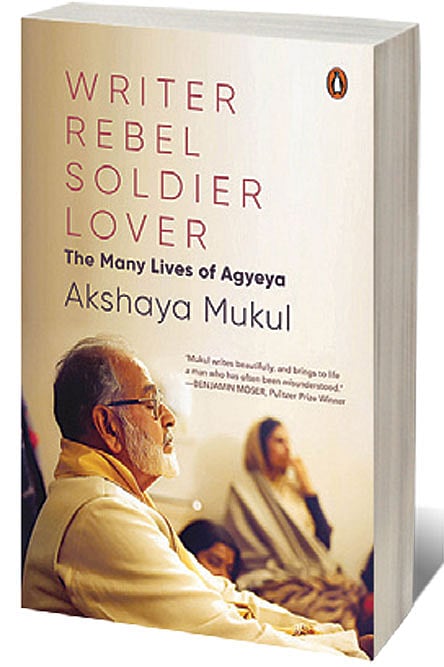

A LITERARY BIOGRAPHY STANDS at the intersection of many disciples. Language, history, political thought, cultural memory, and human narrative collide within its pages. Sachchidanand Hirananda Vatsyayan ‘Agyeya’ was a man of many parts, who lived through a seminal period of Hindi literature. He was born on March 7, 1911 and died on April 4, 1987. His biographer Akshaya Mukul describes his birth at an excavation site in Kushinagar “in an open space, not far from the spot where the Buddha was believed to have breathed his last.” The word “agyeya,” which he adopted as his pen name means “the unknowable”, and the puzzles, paradoxes and contradictions of his life stand testimony to that.

This vast biography, with its mythic scope and texture, is written with precision and passion. It is ironic, and also appropriate, that this first comprehensive biography of the man who was considered a foundational figure of modern Hindi literature, a man whose “stance on language politics bordered on Hindi chauvinism” is written in English. It is also appropriate because of the cosmopolitanism of Agyeya’s scholarship, even though he was insistent that “an Indian writer could not successfully write fiction and poetry in the colonizer’s tongue.”

Agyeya grew up in a multilingual environment, as his father had a transferable job with the British government. His first language was in a sense English, and he writes that he used to dream in English. He took pains to ground himself in his neglected mother tongue and affirmed that he had only learnt Hindi by “deliberate effort, in a hostile atmosphere”.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

This ambitious biography begins with Alexander Cunningham, the first director-general of the Archaeological Survey of India, and the effort to locate the site of the Buddha’s death. Agyeya’s father, Pandit Hirananda Sastri, had been hired by the ASI. By page 11, we encounter the young Sachcha’s precocious talent for poetry. It is at the age of four that he says of a spinning top he plays with “Nachat hai bhumi ri—O the earth is dancing”. At the age of five he drops out of his convent school after a reprimand by a disciplinarian nun. A rigorous course of home schooling begins, which included English, Hindi, Persian and above all Sanskrit. This early rigorous grounding in classical texts was to provide a firm philosophical base for his later endeavours.

We meet Agyeya in his youthful revolutionary days, when, to quote his prison diaries, he had pledged himself to “the undying flame of a revolutionary ideal”. The political activism led to conspiracies and jail sentences, and the cover of a soap factory to manufacture explosives. This was followed by courtroom dramas, betrayals, and struggles with the harsh realities of the British Raj. However, there was also the intense reading, both revolutionary and romantic, and the growing realisation that he was at heart a writer. Sometime in 1932, Premchand, the leading light of the Progressive Writers’ Association, and editor of the literary journal Hans, encountered Vatsyayan’s stories. They met his rigorous standards; the story did not bear his name; Premchand conferred the pen name “Agyeya”— unknowable—to the byline.

Mukul’s unputdownable book is packed with literary and social history and gives an exhilarating feel of those dark days, which were yet so full of hope and conviction. It follows the publication of Agyeya’s major work and the sure blossoming of his genius. There is also mention of the stalwarts of world literature such as Anatole France, John Galsworthy, Emile Zola etc. We read of Russian literature, European literature, Bangla writing. We read of DH Lawrence, and of the pull of Nicholas Roerich, and the influence and disenchantment with the Chhayavad movement. We haven’t crossed page 100 yet, and there are 650 more to go, including the references, acknowledgements, and index.

How does one review a book like this one? How could one man have compressed so much intensity into a single life? It is a dizzying read, a joyous adventure, and as one turns the pages one glimpses an all too human figure, the frailties and vanities that come with fame, and accompany genius. We read of his time in the British Indian Army, where, forever the shapeshifter, he is now Captain Vatsyayan. We see him through his marriages, his affairs, his aspirations, we see him scaling new heights of success, we see him coping with the despondent realities of a writer’s life. We witness all too familiar factions and rivalries between writers. We read of the All India Writers’ Conference, which reached out to a dazzling array of writers across ideologies and political persuasions with a rare generosity of spirit.

We see a language being fired; we see a literature being forged.

It is difficult to judge a writer by his lived life. Agyeya, the unknowable, was a man convinced of his genius. Like many other men of genius (rarely women) he considered himself exempt from the rules. Fidelity and loyalty were not his most abiding qualities. There was his complex relationship with his older cousin Indumati. His brief, loveless first marriage, to Santosh Kashyap, was “a big commitment,” which he could “not fulfil”. The relationships and affairs that preceded and followed it suggest a restless search, for companionship, for romance, for mental and physical stimulation. Mukul has written of Agyeya’s personal and emotional life with depth and discretion. I was particularly moved by the pages that took us to the tender, heartfelt, and yet sparky letters from Kripa Sen, his secret lover in the early 1940s, who was later immortalised as Rekha in Nadi ke Dvip. In his thoughtful introduction, Mukul comments, “His relationships with women—each of them talented in her own right— tended to be extractive, whether financially or for creative gain.” Agyeya’s deepest, best known relationships were with the formidably beautiful and talented Kapila Vatsyayan, who he married in 1956, and with Ila Dalmia, both muse and amanuensis, who remained with him until the end. Kapila was 27 when he married her, and he 46. She was also the niece of his previous wife, Santosh. She remained his legally wedded wife, although her authorised biography has barely referred to the relationship.

Agyeya met Ila Dalmia sometime in 1967 or 1968. She was 23, and he was about 30 years older. The two decades they spent together were fruitful and creative, with travels across Europe and America, new friends, and incursions into new areas of creativity. Mukul comments that Ila Dalmia was “instrumental in burnishing Agyeya’s reputation in his old age”. She was in many ways to become the custodian of his life and legacy.

When Agyeya died, the editorial in the Navbharat Times declared, “a vast silence has fallen over Hindi literature.” The cult around him, and his mystique, flourished after his death, though it is difficult to evaluate his continuing impact on today’s generation and contemporary Hindi writing. A year after Agyeya’s demise, Ila Dalmia published her first novel, which she had been working on for some time. Titled Chhat par Aparna, it was discernibly autobiographical in its theme of a young woman from a wealthy family and her older lover.

Most of the dramatis personae in this multi-layered biography are no longer with us. This resonant narrative is a magnificent work of scholarship, researched with passion and told with detachment. It chronicles an era and links the history of recent Hindi literature with the intellectual life of the nation. It also provides a crucial bridge between the determined insularity of Hindi and the sometimes rootless cosmopolitanism of the Indian-English literati—a bridge that Agyeya himself effortlessly crossed and recrossed in his inner life and literary career. The tome contains over 200 pages of notes, primary and secondary references, indexes and acknowledgments. These document the deep friendships, rivalries and discords, the concerns and dilemmas, that obsessed a generation that was searching for its true voice and identity through a time of transition.

The book opens with Agyeya’s poem ‘Mujhe Aaj Hasna Hai’—masterfully translated by Ranjit Hoskote as ‘I Should Laugh Today’. “One day I’ll / be found lying dead by the roadside / and people will keep turning to look and ask by right / Why were we not informed earlier / that there’s still life in him?” (from ‘Sagar Mudra’, 1971)

Akshaya Mukul’s epic endeavour proves that there is still life in Sachchidanand Hirananda Vatsyayan Agyeya. The embers are still aglow.