A Poet’s Prose

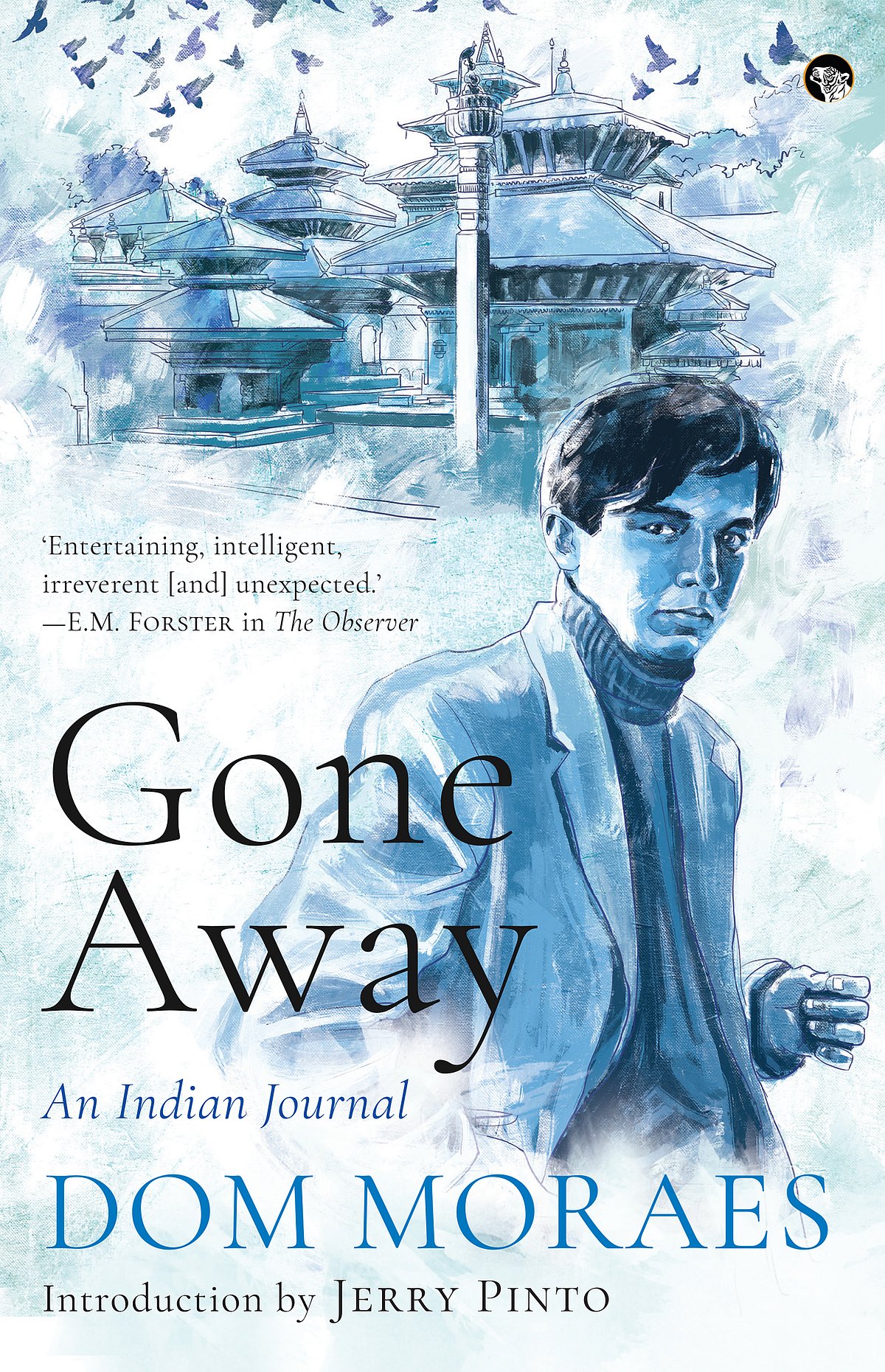

That Dom Moraes (1938-2004) is a gentle giant in Indian poetry in English does not need repeating; Moraes is a part of our mental verse-scapes. Less known to most of us is his work in prose. Moraes was a prolific and celebrated writer of columns, essays, profiles and other forms of literary nonfiction; Gone Away falls squarely into this category. Apparently his third book, it came out in 1960 first, and Speaking Tiger republished it this month.

Gone Away is his breezy account of his impressions of Bombay, Delhi, Kathmandu and other places in Nepal, Sikkim etcetera. These impressions were collected through journeys conducted in the period August-November 1959. It was a time when Moraes was in love with an unspecified someone in the United Kingdom, where he had gone to earn his Bachelor of Arts at Oxford, and he came back to his hometown Bombay very much still in love, and aching with it.

It is to that someone that the book is addressed. It is through this lens that we are meant to read the book. And so, I read it as an account of repressed, anguished longing expressed in subtext and inadequately salved by adventure; a memoir serving as a bridge over a mountain river of loneliness. Read objectively, the book is an account of a grand adventure, not a scholarly work. It is engaging, entertaining, and piques our interest in the times and people it describes. To slake our interest fully was never its brief.

Even in this nonfiction book, the poet in Moraes is never asleep, the writing is precisely crafted, and symbols and metaphors and turns of phrase and vivid images make the whole text lambent. This line of speech does double duty, for instance: ‘‘You should never listen to people’s directions in India,’ she said briskly. ‘They are always wrong.’’ The lines occur in the subtext of the young Indian republic floundering as it finds its way forward. Sample this deeply-felt image, driven home by a deft word choice: ‘He has vivid blue eyes like stains in a bronzed face.’ Or this description of Jawaharlal Nehru: ‘The still centre moved off towards Parliament and the regathering hurricane.’ Or this word-picture of an airport waiting room: ‘... the impersonal community of the about-to-depart, masked in magazines’. At times, though, Moraes displays almost a caricaturising impulse, with rather jarring descriptions such as ‘slant-eyed’, or in another place, ‘a black lizard’s tongue’. Moraes belonged to a different time, though. Besides, in his introduction to Gone Away, writer Jerry Pinto says, ‘You feel in all this the sense of a watchful alien, not unsympathetic to local life forms but not quite understanding them either.’ This is not necessarily a bad thing for a writer; it may account for Moraes’ lack of judgement of people in the book. Throughout Gone Away, it is clear that Moraes may not have been at home anywhere, though in the book he also hints that he was at greater ease to some extent in London than in his hometown Bombay.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

It also seems that Moraes related to people in his own singular way. The son of a well-known journalist, well-connected Moraes is chatting with Jawaharlal Nehru and the Dalai Lama one day, with major poets (Buddhadeva Bose, Laxmi Prasad Devkota) and painters the next (MF Husain, Jamini Roy) the next, and visiting hooch dens in prohibition-era Bombay (for sampling the wares) and brothels in Calcutta (only for research). We are also given a flavour of the social and political realities of the time, with dissatisfaction brewing over Nehru’s administration of the country, particularly with reports coming in of Chinese troops massing on the Tibetan border with Sikkim. In the final few pages of the book, Moraes even approaches the Chinese troops, and ends up having to run back to safer ground.

Gone Away is a delicious piece of literary journalism that young practitioners of the craft would do well to imbibe. And it offers a flavour of 1950’s India that will be of interest to the general audience. A word of praise also for the publisher, Speaking Tiger, which has republished a number of books by this major Indian writer. This should prompt other Indian publishers to dive into the riches in their out-of-print catalogues, where a lot of Indian culture lies paralysed.