‘A Jolt at the End of the Wire’

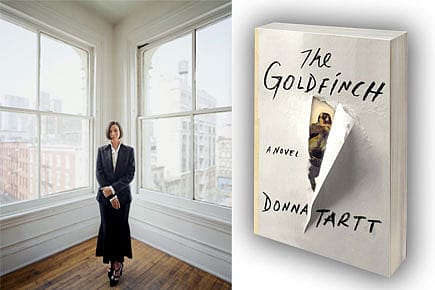

In her new novel The Goldfinch, Donna Tartt offers us the meaning of life. There's no way of knowing what makes her sublime, but perhaps it doesn't matter

Donna Tartt is really code, as in 'Dear Lord, Bless my family and thank you for the bounty set before us, Donna Tartt'. It is a punctuation that gives thanks for those who have made sense out of chaos and brought light where there was once darkness.

Is it any wonder then that her latest novel, The Goldfinch, gives you, quite literally, the answer to the meaning of life? Or that the journey to the last five pages where it is offered to you gratis is so poetic, it physically hurts somewhere in the region of your heart?

Books sometimes come your way when you need them most. The Brothers Karamazov when you are struggling with the concept of God, or Catch-22 when you're ambivalent about the virtues of war. Or, if you have come to the crossroads we all must come to and wondered why you bothered, The Goldfinch.

How does one judge Tartt's worth? Does her gender lift her writing above the ordinary? Does it matter how long she laboured over this book in particular? Is there a single overriding force that makes an author something Else? William Blake was certainly 'Other', touched by the divine, happily embracing visions, plucking words from the sky and padding up his verses. But as Ed Friedlander wrote when discussing Blake's Tyger, 'just because something is diagnosable, it isn't necessarily a disease.'

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

An argument could be made that the greater the 'derangement of all the senses', the greater the writer, as both Arthur Rimbaud and Franz Kafka could attest. Rimbaud called it something to endure if you had the fortune of being 'a born poet'. 'It's really not my fault,' he said.

Maybe it's not madness but subliminal longing that makes a writer special.

In her first novel The Secret History (1992), Tartt tapped into a desire within us all to stay young—for a time when the future is still out there, there is hope, dreams have yet to reduce to sawdust. She pulled us into a clique as cool as its members were siren-like, sweeping through university corridors—and what's a murder or two between friends?

There is nothing more magical than being in a 'gang' during your student years, or owning a best friend who has the right to bully you and adore you in equal measure—and Tartt took this in the least expected direction, but with such sleight of hand in terms of language, atmosphere and ballast that she, too, was instantly recognisable as 'Other'.

You can tap into the yearning more directly, of course, like Sarah Collins Honenberger did with Catcher, Caught, taking the baton from JD Salinger, the master himself. Honenberger caught not just the tragic, transitory history of all our lives but told her story through the voice of a 15-year-old, authentically.

Holden Caulfield continues to live in the popular imagination every time we stay true. That's what being young is, whether you're 15 or 50. Tartt, in that sense, is perennially around 21, perfectly poised, her fascination with Youth—and Death—unending.

This fascination culminates in The Goldfinch, which, 20 years in the making, with its unforgettable family dynamics and spotlight on our collective heart of darkness, has to be Tartt's definitive work.

13-year-old Theo Decker loses his mother in a bomb attack and must navigate what is pretty much a parallel universe. He moves from stability and unconditional love to a desert where he has to find some solace in a fate unasked for. His first stop is with childhood buddy Andy and his equally dysfunctional but richer family.

Andy's mother, Mrs Barbour, with a voice 'hollow and infinitely far away'—almost like Sandra Bullock in The Blind Side—is, for my money, ready for the big screen herself. We are always wondering which way she'll flip. Just as you're getting ready to dismiss her Park Avenue posh, she will steel magnolia all encroachers into submission, and she has an italicised way of decimating the competition that is rather endearing. Because of it, she makes sure a child has time to grieve.

How Tartt expresses that grief, like a tsunami leaving behind 'a brackish wreck' where Theo can hardly remember 'the world had ever been anything but dead', it stays with you.

Despite what Tartt's readers call her—hilariously, everything from 'mesmerising' to 'the literary equivalent to novocaine'—she shares a little of her power with you each time you dip into The Goldfinch.

It's spot-on, the way she captures the snide remarks of teen boys against their fathers, when Andy says learning to read nautical flags is only crucial if one 'needs to hail a passing tugboat'—Andy is difficult to reach, anyway, 'a planet without an atmosphere'. Or the way she describes Theo's father as someone who 'had that crazed and slightly heroic look of schoolboy insolence, all the more stirring since it was drifting towards autumn, half-ruined and careless of itself'. Or the way Theo sees Hobie, whom he meets because of the bombing, as 'an elegant but mistreated polar bear'.

The painting of a goldfinch gives Theo a mooring. It is reassuring 'just as it was reassuring to know that far away, whales swam untroubled in Baltic waters and monks in arcane time zones chanted ceaselessly for the salvation of the world'.

But we see how the blast sets out ripples of unease in Theo when he suffers from tinnitus, or in the way he jumps if someone puts a hand on his shoulder, or how he sees his mother in Mrs Barbour (cleverly underscored by the fact that both talk about Rembrandt the same way), or how he and his great love and fellow blast victim suffer the aftershocks in a dozen daily tortures.

Our first glimpse of the meaning-of-life motif is during adult Theo's drug withdrawal, when he sees the world as 'soft fruit about to spoil', and in his fiancé Kitsy's reaction to being caught with another man, for which pragmatic is too warm a word. Further along, there is another glimpse when not-all-bad boy Boris tells Theo nothing needs to be pounced on and judged immediately, that 'fate is cruel but maybe not random'.

The Tartt perspective is unnerving. She's the kind of thinker who could write about a clear blue sky and make it a portent of the apocalypse. Only Theo could arrive in Amsterdam and visualise it as 'a place where you might come to let the water close over your head'.

Like us, Tartt is preoccupied with death and worry, and opens up several paths to dealing with it. You could get stoned and feel 'magnificent detachment', or figure out that worry is nothing but a colossal waste of time.

Or you could feel, like Theo does when he gets ready for the water to close over his head, like 'the dentist had leaned in under the lamps and said almost done'. You could also find 'a jolt at the end of the wire', in something you discover when throwing yourself 'head first and laughing into the holy rage calling your name'.

VS Naipaul famously said that he could start reading something and know immediately whether it was by a man or a woman, and in any case it didn't matter a damn because they were "unequal to me". The Guardian, meanwhile, came up with a simple quiz to see whether all those not equal to Naipaul could tell an author's sex. Take the test, you'll fail. It's impossible to decide whether a work has merit based on the sexual organs possessed by its author, let alone how long it took to write.

How long should it take to get out that beast wriggling in your chest anyway? Jack Kerouac apparently took seven years to make notes, but only three weeks to write On The Road, no doubt screaming 'Yes! Yes! Yes! Yes!' all the way. Charles Dickens wrote in stops and starts because he had to make a living in the serial publication style popular in 19th Century England. That style also allowed him to rewrite, tone down, add elements and delete, which is what many authors mean when they say it took them 12 years to do such-and-such.

Journalist Patrick Ness once wrote, 'It's a truism that a debut album is often so good because the artist has taken an entire life to write it.' The key word is 'often'. With some, it's the works that come later. Like Glenn Duncan's The Last Werewolf or John Kennedy Toole's Confederacy of Dunces (although, to be fair, Toole wrote The Neon Bible when he was 16).

Our scrambling in the hearth for characteristics of the 'Other' may be unnecessary, however. There's a good reason why Georgette Heyer never granted interviews and why Salinger said "I write just for myself and my own pleasure". Why examine the feasts we were promised and are sometimes given?

In the end it's this simple: it could be the story, it could be how well you weave it; it could be Pride & Prejudice, it could be The Happy Prince. But if it changes a reader's life, it's pure gravy.

We may be 'tethered to fly on the shortest of chains' yet still refuse 'to pull back from the world'. In the end, that is all there is. Trust Donna Tartt to teach you.

The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt is now available in Paperback from Hachette India, 784 pages, Rs 799