A Female Gaze

THE MEMSAHIB—AS the British woman who came to India was called––has often been portrayed in a less than favourable light. The fact that they did not directly serve the empire and were in colonial India as the wives of the empire officials in service became a surreptitious reason for undermining their personalities.

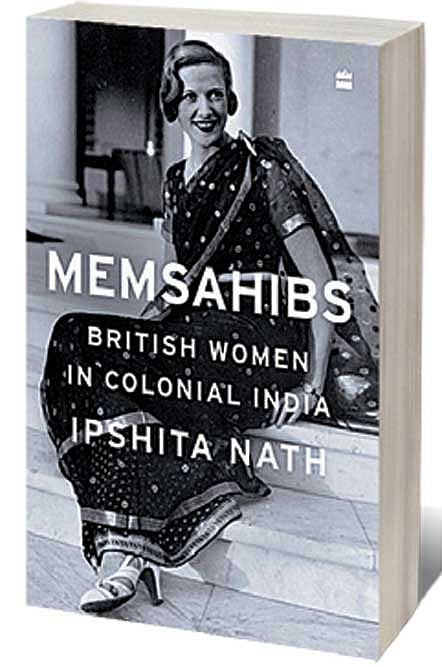

In the book, Memsahibs: British Women in Colonial India, Ipshita Nath uses letters, memoirs and reminiscences of colonial women to show how they navigated life in a country far away from their own, both physically and culturally. The first-hand glimpses create an understanding of British women, who mostly did not shy away from the dangers and disturbances in their new homes but instead tried to find their place within the space allowed to them.

In the first chapter, we see how the excitement of the women gets dampened by the difficulties experienced by them while travelling. External factors like hurricanes, shipwrecks, pirates tangled with internal problems of disease, accidents on board to make their journeys perilous. Minnie and Archie Wood travelling after their wedding found their ship cramped and unsanitary. The dining room was too small and the cabins were sparse.

As the author takes us through the journeys made by the British women from early 19th century to the 20th century, readers also get a glimpse of how travel modes and routes improved to benefit passenger movement and trade. Travelling was a favourite pastime among the British and they travelled quite a lot for both business and pleasure. Even though modes of travel were less than comfortable and there was a danger of encounters with robbers, wild animals and poisonous insects, the colonial men and women enjoyed their outstation journeys. The women especially looked forward to these trips in spite of the dangers because it gave them a respite from the boredom of everyday life. Some women even travelled by themselves accompanied by servants, later writing about the threats and dangers they faced during those travels. Ursula Graham Bower, an anthropologist and guerrilla fighter, who did not believe in ghosts, recounts how she had to acknowledge the presence of one in the house she stayed while travelling through the jungles in the Naga region.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

The British took to hunting or shikar in a big way when the sport loving royalty of India introduced them to it. Women too found the sport fascinating and accompanied their partners. Some women like Emily Eden often led hunting groups. Laurie Johnson set a record by killing a tiger measuring up to 12 feet.

One of the things that made the colonisers wary was the threat of diseases and infections. The women especially tried to have basic knowledge of illnesses and the medicines to cure them. “If someone in the neighbourhood fell sick, they were quite happy whipping up syrups and potions from their personal medicine chests… Castor oil, grey powder, rhubarb, ipecacuanha, were some of the staples.” Sometimes helping out with medicines also got them in trouble since there was an aversion to western medicine among the Indians.

Memsahibs have often had to take the criticism of being frivolous and unmindful of their husband’s official duties. Their love for hill stations and prolonged vacations without their partners have been documented in various mediums. “Mr. Kipling’s Jill is the type of Anglo Indian wife best known to English readers; yet how much less than little do they know of the subtle temptations which beset her at every turn!” writes Maud Driver in 1909.

The author has gone into great detail to draw the lives of the British women who came to India following their husbands. One hiccup in the otherwise smooth read was the random placing of extracts of women’s writings. Perhaps placing extracts at the beginning of each section would have been helpful. However, this book showcases the extraordinary resilience and courage of the memsahibs in their attempt to live in a land far away from their own.