Piecing Together Our Fragmented World

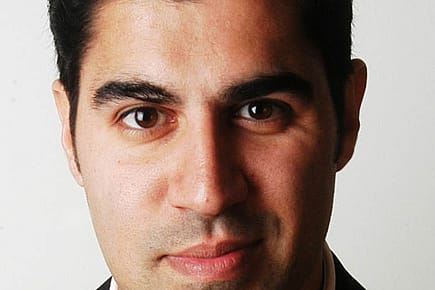

Born in Kanpur, raised in Abu Dhabi and the US, Parag Khanna is a New Yorker, global citizen, bestselling author, political analyst and more at just 32

Parag Khanna can't sit still. The 32-year-old sweeps into a Manhattan restaurant and settles into a booth along the wall of a spacious bar. He orders a Diet Coke and pounds out a couple quick messages on his BlackBerry before launching into a description of his work: "I want to represent ideas and agendas and themes and goals." He admits that his recent accomplishments—a bestselling book, being named in Wired magazine's 15-person 'Smart List' and Esquire's 75 most influential people—have not satisfied his huge, if vague, ambitions. "I want to see action; accolades are great—great at parties, great for networking—but I'm first and foremost interested in the promotion of actionable ideas."

He's had more than a few of them. Years ago it was Bollystan, the idea that a rising South Asian diaspora—young, educated, ambitious, outspoken and tech-savvy—was embedding a potent new vision of the Subcontinent deep into the global consciousness. In 2007, he passed on a few actionable military ideas as an adviser to US Special Forces in Iraq and Afghanistan. Last year, he gave us The Second World, his first book, which posited that the 40 or so states that make up a broad middle layer between the world powers and poorest countries would come to define the next few decades of international relations. More recently, he dubbed this era a period of 'neomedievalism'—a return to weak states and powerful non-state actors like Al Qaeda and Bill Gates.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Khanna's ideas are often like jigsaw puzzles, fitting unlikely shards into an unpredictable whole. He is part of a globalised, post-9/11 intellectual ferment likely to define this unpredictable century. He is a one-man whirr of productivity, everywhere at once—on TV, in the papers, in the magazines—and almost impossible to pin down. "Being friends with Parag is like being friends with ten different people," says Jeremy Goldberg, who runs his own non-profit consultancy in New York and has been friends with Khanna since the late 1990s. "He has such a diverse set of relationships, interests and experiences, and such vast knowledge to share—that is, if you can ever get him to slow down long enough to have dinner or a drink."

That restlessness is in his blood. Khanna's family is originally from Punjab, but his father Sushil's work with Tata Exports took them all over the world. "We have, as a family, been in constant motion," says Parag's mother, Manjula Khanna, a teacher and telecom consultant. "My husband has been a globetrotter himself, and lived in 11 countries."

Parag was born in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh in 1977. He lived in Abu Dhabi until he was five, then moved with his family to New York. On his brother Gaurav's insistence, he became an avid reader. But it was a year in Germany as an exchange student "out of the sheltered enclave of suburban New York" and a backpacker trail across Europe that really focused his mind, says Khanna. "That was a big deal."

In 1999, Khanna launched, with Goldberg, the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, then became a research associate at the Council on Foreign Relations. The next few years included stints at the World Economic Forum and the Brookings Institution. Last year, he advised the Obama 2008 foreign policy team. In addition to hosting a talk show on MTV, these days he commutes from his Manhattan home to the New America Foundation in Washington DC, where he directs the Global Governance Initiative.

Khanna considers himself a New Yorker, but this is an over-simplification. "He can put himself in the mind of people of other countries in a very sharp way," says Robert Kaplan, a political analyst who has become something of a mentor, "We're entering a post-national age, and Parag is very well placed to epitomise that consciousness." His mind spans South Asian poverty with as much ease as Davos deliberations.

One of his latest ideas is post-colonial entropy, which refers to the decline of central governmental authority in the developing world. It's happening across Africa and even South Asia, most acutely in Pakistan. Is the state in the midst of a slow-motion collapse? Last week, while the Pakistan army battled the Taliban, the US envoy to the region Richard Holbrooke urged the American Congress to approve an annual $1.5 billion in non-military aid. He added that although things were tough, Pakistan was not in danger of becoming a failed state.

"Pakistan has fallen," Khanna counters. "You don't have to wait for the headline." The internal tug-of-war, he says, has rendered elections meaningless. "Who cares about elections? Who says that's how you measure power?" asks Khanna. "Political power is just one way of looking at power; it's not necessarily the most important one."

Khanna's wife, Ayesha, is a financial services consultant of Pakistani origin. Any day now, she will give birth to their first child. Khanna is looking forward to fatherhood and to a career path he's still figuring out. "The reason I don't aspire to US government office is because I don't want to represent one country," says Khanna.

His mother thinks he's too outspoken for politics. Kaplan sees a policy analyst. Goldberg envisions a terrific professor at a prestigious university, and author. His next book, How to Run the World, suggests grander ambitions. "The book is meant to be a statement on how the dotorg, dotcom and dotgov worlds come together to set the rules of global governance," Khanna explains. There are plenty of pieces to put together.