Guns and Poses

The US exerts strict controls on war photography. Correspondents go embedded with military units. And the Pentagon plays photo editor. Call it war choreography

ON A windswept Delaware air field last week, US Air Force Staff Sgt Phillip A Myers became the first fallen American soldier to be publicly welcomed home in 18 years. President Obama had just lifted the Pentagon's media ban, which President George HW Bush instituted in 1991, during the Gulf War, and his son continued for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Dozens of photographers snapped photos of sombre-faced soldiers silently bearing Myers' flag-draped coffin, and the images were broadcast on television across the globe. But while coverage of killed US soldiers offers a closer look at the real cost of American involvement in these wars—the toll is nearing 5,000 now—it also highlights the air-tight control on media access to this era's military conflicts.

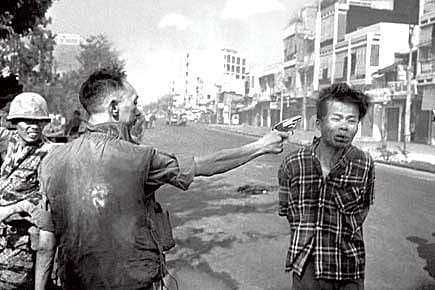

A recent show of photojournalist Eddie Adams' war images is a case in point. Adams shot the Vietnam War for the Associated Press, and he's most well known for his Pulitzer Prize-winning 1968 image of a Vietnamese general executing a handcuffed prisoner at point-blank range in broad daylight on a Saigon street.

The image changed Adams' life, and some say it helped end the war. But the way the image came to be shows how lax controls were on war correspondents even a few decades ago. Adams was walking the streets of Cholon, the Chinese section of the Vietnamese capital, when he saw a soldier drag a man out of a building. In An Unlikely Weapon: The Eddie Adams Story, a documentary released recently (there's also a book, Eddie Adams: Vietnam), he says: "They were taking him by the hand and pulled him out in the street. Now any photographer, when you grab a prisoner, in New York or something, you just follow him, and it's a picture. You follow until he is put into a wagon and driven away."

But there was no wagon, and the prisoner wasn't driven away. Instead, General Nguyen Ngoc Loan stepped in and raised a pistol to the man's head. A few feet away, Adams started clicking. One just happened to capture the general's bullet entering the prisoner's head.

The exhibition, showing in Brooklyn and put together by Adams' wife Alyssa, is full of such powerfully intimate images. In one, a Vietnamese youth is interrogated with a spear at his throat. In another, a marine speaking on a phone in the field looks to be under intense pressure.

Such close-up, storytelling portraiture is practically impossible today. War correspondents must embed with a unit, and in doing so, surrender editorial control. Even if such photos could be snapped today, getting them passed Pentagon censors and into print would take an act of God.

"Photographers had incredible access, which you don't get anymore," Hal Buell, Adams' photo editor during the war, recently told National Public Radio. "No war was ever photographed the way Vietnam was, and no war will ever be photographed again the way Vietnam was…"

The infamous Abu Ghraib photos—of Iraqi prisoners strung up and hooded, and naked on all fours—were all taken by amateurs, soldiers themselves, and were held by the Pentagon until a news leak forced them to go public.

So what's been lost with the stricter media controls? What's happening in Iraq and Afghanistan that we don't see? Another revered war correspondent from an earlier era offers some insight.

During World War II, Ernie Pyle marched, ate and slept in the mud with American soldiers. In finely-wrought vignettes that could never be filed today, he brought the immediacy of war home more viscerally than any flag-draped coffin—such as in this scene with an artillery battery in Italy, 1942: "One night about eight of our crew were lying or kneeling around a blanket in the big tent, playing poker by the light of two candles… the valley and the mountains all around us were full of the dreadful noise of cannon. There was a lull in the talk among the players, and then out of a clear sky one of the boys, almost as though talking in his sleep, said, 'War, my friends, is a silly business. War is the craziest thing I ever heard of.' And then another said, mainly to himself, 'I wish there wasn't no more blankety-blank war no more at all."