Patel the Most Monumental

IN 1994, KAPIL DEV surpassed Richard Hadlee's haul of 431 Test wickets. Almost a decade earlier, in the 1986-87 season, Sunil Gavaskar had reached the milestone of 10,000 runs in Test cricket. And a half-decade after Kapil, Sachin Tendulkar would score his first Test double hundred in 1999. Binding these temporally demarcated statistics in the annals of cricketing history is space—a particular and special space. The Motera stadium in Ahmedabad.

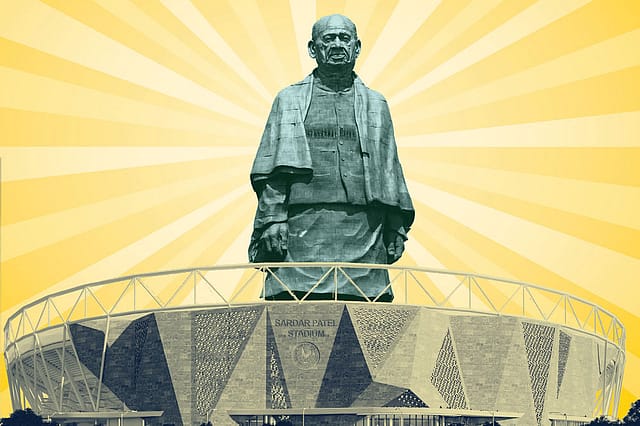

The Sardar Patel Stadium is big. It was rebuilt, beginning in 2016, to make it the largest cricket stadium in the world, with a capacity of 110,000, leaving the Melbourne Cricket Ground a safe 10,000 seats behind. In the process, it also turned out to be the second largest stadium on the planet. Even then, Pyongyang's Rungrado May Day Stadium beats Motera by a mere 4,000 in seating capacity. And February 24th has left Motera bigger, now that more than the tad circumscribed cricketing world can picture the size of our giant.

The fact of size, or scale, has wrapped itself rather intimately as an idea around the name Patel. Take the Statue of Unity. Also dedicated to the self-same Patel, a giant among women and men, without whom the truncated political map of independent India would have shrunk still. At 182 metres, it is the tallest statue in the world. Statistics again show how big the gap is that must be minded by those left below. Its nearest rival, the Spring Temple Buddha in the People's Republic, is almost 30 metres shorter at 153. The Statue of Liberty is only 93 metres. Rio's Cristo Redentor that towers over the city and the sea from the hills is optical trickery, with the filming done almost always from above. The Redeemer with his outstretched arms is no taller than 38 metres.

Rule Americana

16 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 54

Living with Trump's Imperium

All symbols matter. Big symbols, tangible in concrete and metal, matter more. They amplify the message. That would appear to make both semiotic and semantic sense. It isn't reification. What we had in the beginning wasn't the idea.

Instead, the idea is the product of what we have constructed with material from the real world. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel is now an idea in the minds of those who behold his statue.

To the world outside that witnessed 'Namaste Trump' at Motera, the power of Patels, not of a Patel, is an idea reinforced. And they would know, given that 10 per cent of people of Indian origin in Donald Trump's country, reportedly, are Patels. (According to some estimates, there are about 150,000 Patels each in the UK and the US.) The success of the Patels abroad, notwithstanding motel jokes, couldn't be kept out of sitcoms, even if such success was rarely given more than the vaguest contours. But the average British or American placing of the name would not locate it outside the bracket of privilege.

The real world, remarkably, continues to be affected little by the march of the social sciences. Thus, when the Patidar agitation for reservations began in Gujarat in 2015, that same bracket—privilege—was tagged to the name of the community in headlines that took off mostly from what was known of Patels. Typically, 'Privileged Patels of Gujarat fight to be given low caste status' (a headline in The Daily Telegraph from October 2015).

'Patidar' pertains to holders of land. Land-holding is feudal society's first big marker of privilege, placing the landholder above those that don't hold land. Yet, the majority of Patels—Kadvas and Leuvas—were tillers of land whose socio-economic status changed rapidly after the post-independence tenancy reforms in Bombay State, Kutch and Saurashtra. The change in status entailed legislative representation and government posts. This was also the beginning of Patel entrenchment in trade and industry. As levels of education improved with each new generation, the Patels aimed higher and bigger. What it led to, inevitably it would seem with decades of hindsight, was a head-on collision with the beneficiaries of reservations. The Patels had everything. Or almost. With SC/STs and then OBCs coming under the umbrella of reservations, and the Congress ensuring its hold on power with its KHAM (Kshatriya, Harijan, Adivasi, Muslim) formula, the Patels were outside the margins and politically irrelevant. But the scales of fortune turned once more. No sooner had Madhavsinh Solanki delivered the Congress a record 149 seats in the 1985 Assembly polls was he out of office in the aftermath of communal riots triggered by anti-reservation protests. It would take the BJP another decade to form its first government in the state but its rise had begun and the Congress in Gujarat had stepped on quicksand. Behind this tale of two parties was Patel power.

Little wonder then that when the political winds changed again in 2015, there was a Patel behind it. On the back of Hardik Patel, the Congress resurrected itself in local elections and then did better than expected in the 2017 Assembly polls, winning 77 of the 182 seats, a gain of 16, which was exactly the number of seats the BJP lost from 2012. None of that would matter, of course, in 2019 when the BJP took all 26 Lok Sabha seats in Gujarat. But the story in Gujarat of these four years was speculation (and calculations) about the Patel vote and where it would end up, given the all-round assumption that a Patel vote would go to a Patel and the estimate that Patels were key to almost 80 Assembly seats, comprising more than 20 per cent of the state's electorate and 14 per cent of its population.

Over four years of tumult, every other fact about the Patels had held good. Real estate (Parshwanath), consumer perishables (Nirma), healthcare (Cadila), diamond trade (Hari Krishna), pharmaceuticals (Lincoln), ceramics—name an industry prominent in and out of Gujarat and it would be difficult not to find a Patel associated with it.

The Patels have grown steadily since at least the 1960s. Markers to their influence are ubiquitous. And some might say unnecessary. Even the rupture of the Patidar agitation only served to spell out the import of their name. Yet, post-2015, there is a catharsis of sorts in returning to the Patel who stood the tallest. And still does in his 182-metre incarnation above iron, oblivious to wind and rain and quakes. There was a release of tension, too, to say nothing of the spectacle, in watching 'Namaste Trump' choreograph itself to our collective memory without departures from script. The unlikely President was impressed, perhaps conquered, by the numbers. We always have the numbers. But at the Sardar Patel Stadium, in the Sardar's own neck of the woods, those numbers, too, were the consequence of size. February 24th had another fallout. This synecdoche of India will leave Indians far and near (and perhaps others) with little doubt that when you think Patel, you think big. Or vice versa.