City of Echoes

Forget anything subversive, or even original. Almost everything they call ‘high street fashion’ in Mumbai is borrowed

Chaya Babu

Chaya Babu

Chaya Babu

|

03 Nov, 2011

Chaya Babu

|

03 Nov, 2011

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/echoes.jpg)

Forget anything subversive, or even original. Almost everything they call ‘high street fashion’ in Mumbai is borrowed

The girl standing next to me at the bar ordering four cosmopolitans is in a hot pink strapless body-hugging dress. It has a few origami-like folds coming up from the waist, and I can see the grain of its shiny fabric. Her friends are at a nearby table, one in a leopard print mini-dress with a sweetheart neckline, another in a tube-like khaki affair reaching just below her knees, and a leggy one wearing a tight ivory lace top tucked into a snug vinyl snakeskin skirt that laces up at the back. The red soles of the leopard girl’s Louboutins flash intermittently, and there’s a tasselled metallic orange Gucci clutch lying discarded on one of the chairs. All the girls have straight black hair, parted to one side and falling to the middle of their backs.

When we arrive later at one of Mumbai’s hotspot clubs, I notice more of the same as we queue up between velvet ropes, not far from the waves crashing on the dark beach. The women are in short dresses, mostly solid, animal-print, or all-over sequins. Aberrations include a baby blue stretchy garment with a large bow affixed to the front and a gold ruched getup bedazzled with jewel vines. A shocking proportion of men are in Ralph Lauren Ts with the polo logo magnified tenfold. Shoes and bags are of recognisable designer labels as well.

In my first few weeks in Mumbai in January, I couldn’t help but wonder if the parading of labels—and a sleek mall with polished tile floors and global names like Burberry, Chanel, an Emporio Armani as well as Mango, Zara and French Connection—explained the typical reaction to the news of my move. “The style there is incredible. Bombay is becoming a new centre of fashion,” an old classmate had reported after a visit. Other friends echoed this.

Was it because there are runway shows that garner worldwide media coverage? Or perhaps the fact that a local edition of Vogue, that revered international fashion bible, started here a few years ago? I had heard so much about this new burgeoning style hub and came here in pursuit of discovering it myself. Thus far, what I’d found most visually captivating were the throngs of barefoot, sun-creased women strolling the streets in colour-blocked saris of deep indigo and marigold or vermillion bandhani.

Undoubtedly, many conversations had also painted a picture of Mumbai as a place rife with contradictions, at once glamorous yet destitute, with riches and rubble suffusing the city’s climate and culture, depending on where you look. I had thought this would provide a lush palette of ideas for diversity of style as well. But nine months later, I’m still at a loss. I continue to search for creativity in expression, the odd and clever combinations of hues, patterns, textures and trimmings that one uses to reflect one’s personality and distinguish oneself, but most of what I see feels mass-produced and sometimes worse—just a poor, singular interpretation of Western style. As a friend who’s new to town put it, “Everyone just tries to be Hollywood.”

“For me, I don’t think that Bombay can be a fashion capital of any sort,” says Kallol Datta, a Kolkata designer who relies on his own eye and signature style preferences rather than forecast reports while creating a collection. His work has included inventive interpretations of kurta-churidar sets as well as slouchy black garments scribbled with profanity. “Most of the girls look like diluted versions of, let’s say, what Seventeen magazine would feature.” Datta thinks that the high street brands that have come to India, driven by what’s on international runways, tend to push a trend-specific approach to dress choices, and it’s this that many people in Mumbai follow with blind and devout fervour.

“When I land in Bombay and I’m going to places, be it Fashion Week or visiting a nightclub or restaurant, or even driving down the street, when I see the girls, it’s all derivatives, right?” Datta says. “I mean, every girl once upon a time was wearing harem pants with a T-shirt, and now they’ve moved onto something else. And it’s the same with guys. When Ed Hardy launched, everybody wore an Ed Hardy T-shirt.”

On my visit home to New York this summer, I relished visions of fresh ingeniouswear more than ever. Driving south down 2nd Avenue one afternoon, I spotted a friend standing on a corner waiting for the ‘Walk’ signal, a cloud of rowdy, burgundy-black curls marking her presence. Her cropped, threadbare tank billowed in the breeze along with white strings hanging from her denim cutoffs, and a purple satiny bra with black polka dots peeked out coyly. Hearing my shouts, she ran after my taxi in her untied combat boots. Fellow pedestrians watched curiously—a pixie-haired girl in a crocheted camisole under a bomber jacket, floral shorts, and dusty cowgirl booties next to a guy in a Panama hat, a navy T-shirt over punch-coloured pants slung low with a silver-studded belt and loafers. Across his chest read, ‘Frankie says relax’ (reference to Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s 1980s track Relax).

Having grown up just north of Manhattan, this variety was a given. Kids in school divided themselves into cliques along lines of style. There were those with dyed black hair, heavy eyeliner, fishnets and dark leather, while others wore bold colours, big jeans, backward baseball caps and sneakers. This latter look, originating in the Bronx, was illustrative of America’s hiphop subculture and became a quintessential example of a fashion movement born of the youth in poor neighbourhoods. Similarly, alternative forms of dress emerged before and after this on the streets in other places such as London and Tokyo. Teddy boys, glam rock, punk, Lolita, cosplay—these loud, subversive styles wove a vivid thread through the more socially acceptable norms of dress, and were definitive of the motley fabric of these fashion-famous cities.

The late Alexander McQueen said, “Between subculture and fashion there is a connection, and it is very important… the clothes that the young wear in the street, the ideas of the rock bands, the clothes in the clubs, [all] influence… fashion design.” McQueen’s work drew heavily upon looks that arose from below, such as Goth and Steampunk, both subcultural attires infused with Victorian corsets, military coats and sometimes elaborate ruffles.

Datta doesn’t see many identifiable subgroups punctuating the landscape of popular fashion in India, but he says that in the Northeast, there are traces of it. “You’ve got a lot of ethnic influences, and you’ve got a lot of pent-up, student-like rebellious angst,” he says. These factors co-mingle to produce youngsters in faded shirts, extremely distressed denims, and faux-designer sneakers, with Naga shawls and guitars hanging off their shoulders. Datta calls this ‘ethno grunge’. In Mumbai, however, such articulations of difference are not very visible.

I spend an afternoon in Versova with Manou, who documents street fashion on his blog, Wearabout, and who could well earn the title of Mumbai’s very own Sartorialist. Most of what he photographs, however, is from other parts of India. This is because of the rarity of finding anything that piques his interest around here. He talks about the lack of vibrant subcultures, an unwillingness to incorporate high and low fashion to craft an individual look, and an overall desire to emulate the West resulting in an acute dearth of originality in Mumbai. “We are more enamoured of the West and by what’s happening in Europe and the US than what’s happening here,” Manou explains.

A memory sticks in Manou’s mind of a night out at a bar around the time High School Musical was released. He counted at least 12 guys with Zack Efron haircuts. “You can understand what kind of stuff people are looking up to,” he says. It’s for this reason that Manou takes to the streets outside Mumbai to feed his photo habit. Most recently, in Salem in Tamil Nadu, he was drawn to the plaid and printed lungis worn by day-labourers. He purchased one for Rs 50 and used it as material to get a blazer stitched, rendering true Indian fashion into a wearable urban style. And in Jodhpur, women captivated him with their stacks of bright bangles, chunky earrings and necklaces. He finds it unfortunate that while there might be hints around the city of grunge or indie Brit fashions, both street styles imported from overseas, the Indian equivalent is mostly overlooked. “It doesn’t have any direction,” he says of what he calls ‘Jodhpur bling.’ “You can recognise that it’s from Rajasthan, but that’s where it stays.”

A handful of Indian designers, notably Datta, Paromita Banerjee, Aneeth Arora, and the sidewalk-to-catwalk pioneer Sabyasachi, do create fashionwear with a genuine feel for local and street ethos, but the interchange between their distinctive aesthetics and the actual people in Mumbai is disappointing. According to Manou, film stars Rani Mukherjee and Vidya Balan had to endorse the now globally-known Sabyasachi, who brought a modern version of the sari to Indian fashion, before his name got the attention it now gets.

“What we showcase on the runway, you don’t necessarily see translate onto the street,” says Datta, who incorporates smaller native elements in his mostly Western designs. “I’ve never made a garment with a zipper in it. I’m all about buttons and tie-ups and strings and drawstrings,” he says. “When you talk about closure details on garments, that, for me, is completely taken off the street.”

For Paromita Banerjee, who is also based in Kolkata, the essence of her work is rooted in India handweaves, like various khadis, matkas and tassar silks, constructed and layered into what she calls an ethno-contemporary look. A recent collection paired these traditional textiles with the patchwork of Japanese peasant-wear and silhouettes that mimicked robes of Tibetan monks. She is passionate about pulling stuff from various regional street styles, which she believes are always more imaginative, untutored and undictated by Bollywood or glossy magazines. “They are the torchbearers of fashion,” Banerjee says of Indians who may only own four or five articles of clothing. “They sort of amalgamate the whole thing and form their own look. And, you know, it looks pretty nice put together.”

She contrasts this with the uniformity that surrounds her when she visits Mumbai. “I am disappointed that people in Bombay seem to be sort of apeing the West,” she says. “With all these branded stores and big labels coming up, people are all wearing the same thing.” Mumbai, famously cosmopolitan as a city, with people of varied backgrounds, cultures and histories all in one place, ought to be especially open to variance and spontaneity in one’s garb, she feels. “There are people from all walks of life,” she says, “And in street style, that’s where the real trends come about.”

Personal style, somehow, gets short shrift in Mumbai. Instead, the city seems to have a penchant for conformity, which hinders people from exploring and experimenting with novel or unusual fashions, so anything that deviates from conventional standards is scarce. Instead of playing with the city’s pulse, energy and kaleidoscopic imagery, using the millions hailing from infinite nooks of this vast subcontinent as inspiration, the all-pervasive tendency is to look West and distance oneself from what is below.

This is not to say that people who embrace and engender uniquewear are wholly nonexistent, but that the Mumbai that is supposed to be a budding world of original, innovative style still has far to go. It is the unexpected mixing of dissimilar sensibilities, something that cannot be handed down from an ivory tower, that lends itself to truly artistic expression. Like Manou, who thinks a rickshaw-wallah’s scarf makes an ideal wrap for a sophisticated woman, more Mumbaikars need to see fashion through their own lens. Until then, this is just a city of fancy new shops, some brilliant designers, and young women who love their LV. Fashionable, in a way, but just not fashionable enough.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

MOst Popular

3

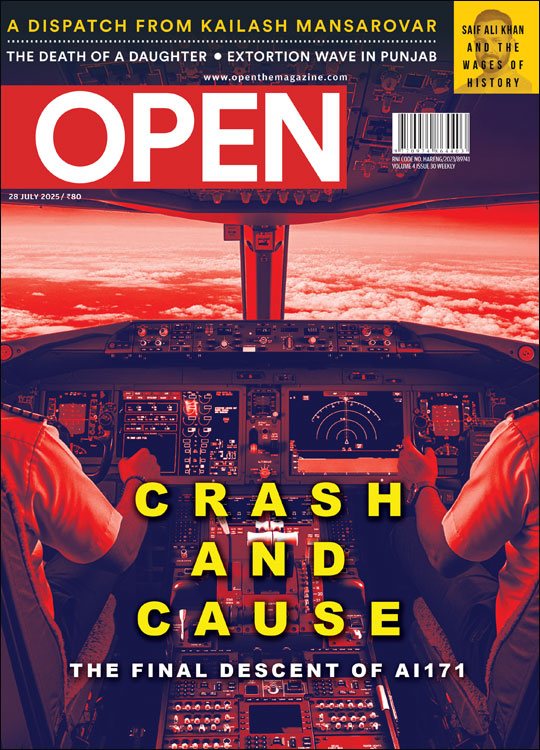

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba