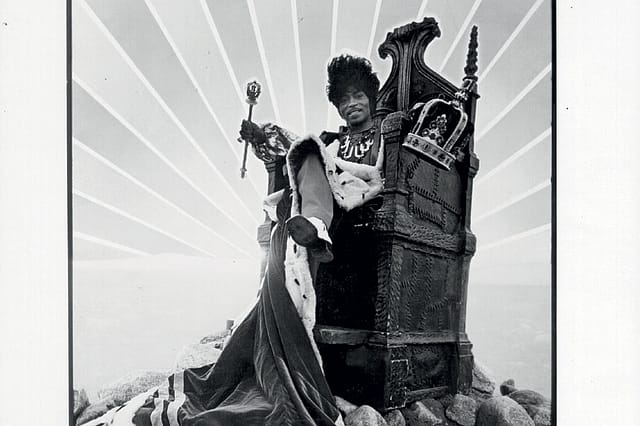

Little Richard (1932-2020): The King and Queen

It is difficult to put a pin to that exact moment when Rock & Roll was born. But if you try, you are likely to find a spot close to the emergence of that sound. With those words—a verbal rendition, it is said, of a drum pattern, which then leads to the rest of the song Tutti Frutti—the world was introduced to a new genre and one of its most important architects, the singer Little Richard. Before this moment, there was an understanding in the music industry that a new audience of young people was emerging, people who were getting restless with the old embarrassing ballads of their parents. But nobody quite knew what this new music was going to be about. But with that sound and that song, the new terms became clear. It was going to be outrageous, energetic, lyrics so simple that it became a kind of teen code incomprehensible to adults, and above all, loud.

Little Richard was central to that moment. He pounded the piano and screamed his songs; every phrase embellished with more squeals. He wore baggy suits with elephant trousers, mascara on his eyelashes, a pencil moustache framing his face, while above, his hair combed backwards into an impossible fountain. He was unapologetically Black and queer.

And yet, Tutti Frutti sold millions. His audiences, a very new element to music then, spanned both White and Black Americans.

Little Richard may have come to prominence with that song, and he was just 20 then. Born as Richard Wayne Penniman, he used to sing solos at the local gospel choir. When he was thrown out of his house in Georgia at around the age of 13 by his bricklayer father because, it is said, of his homosexuality, he began performing professionally. He played at medicine shows and even became a drag queen adopting the stage name Princess Lavonne, later leading to call himself, when he became famous, 'the King and Queen of Rock & Roll'. For about five years, he adopted the name Little Richard and recorded several unsuccessful singles before Tutti Frutti happened.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

Several great songs followed through the 1950s, with his trademark powerhouse energy and screaming vocals—from Long Tall Sally, Slippin' and Slidin', Ready Teddy, Heeby-Jeebies, All Around The World to The Girl Can't Help It and Rip It Up—music that would be revered by later rock greats. Not only his music, even his fashion and showmanship had a profound influence. David Bowie and a young Elton John borrowed the wild outfits, Mick Jagger stole the strut, and Prince snagged both the pencil moustache and the fashion (Little Richard once turned to the camera during an interview to address Prince, 'I was wearing purple before you was wearing it!').

An amusing aside is that when Little Richard crossed over from rhythm and blues—which was then primarily a genre listened to and created by Black Americans and much more playful and sexually frank—to the new Rock & Roll, which had a wider audience, a lot of his music also got scrubbed clean. His song Lucille is actually said to be about a drag queen. Tutti Frutti began as an ode to anal sex. The song's original lyrics, as the story goes, was 'Tutti Frutti, good booty/ If it don't fit, don't force it/ You can grease it, make it easy.' Little Richard had apparently been performing this version for years. The new version's producer, realising the tune's commercial worth, got a songwriter to rewrite the lyrics to the much less playful 'Tutti Frutti, aw rooty/ Tutti Frutti, aw rooty'. Little Richard, it appears, had a difficult relationship with his sexuality. In his authorised biography The Life and Times of Little Richard, he says, as quoted by Rolling Stones, 'Homosexuality is contagious… It's not something you're born with.' He later claimed he was misquoted in some portions of the book. But in 1957, at the height of his success, Little Richard suddenly quit rock music. He said he was renouncing the devil's music for God. He is believed to have become a minister in the Seventh Day Adventist Church. After failing to gain an audience on the evangelical circuit, he returned once again to rock in the mid-1960s. But by then the world was already moving to new artists in the genre he helped kickstart.

He has always been around through the decades, doing songs, appearing in films and making guest appearances on TV. In the 1990s, in a strange twist of fate, he even performed children's songs.

Now he is gone.