Wrung and Hung Out to Dry

Victims of the Saradha scam may not have been educated and alert enough, but an entire system of governance has been caught napping

Prabhash Roy is 52 years old.

He lives "a simple life" in the bylanes of a South Kolkata neighbourhood with his wife and teenage daughter. On 17 April, two days after he had celebrated the Bengali New Year, he walked into Burrabazar's instrument market like he did every working day of the week. He dismissed the first odd glance cast his way and made small talk with some of his clients before he was stopped by an acquaintance and told that the Saradha Group of companies had gone bust and its chairman Sudipta Sen was absconding.

Right there, in the middle of the market where he had generated deposits of upto Rs 13 lakh a month for Sen's group, amid all the commotion and anxious questions of numerous investors, Roy's world began to unravel. "I had been their agent since March 2010, working hard to convince people to invest in schemes run by the group," Roy says. "In one minute I lost everything—people's faith, a lot of money, and a good night's sleep."

A day earlier, on 16 April, another employee of the Saradha Group, Arpita Ghosh had walked into the electronics complex police station in Kolkata's Salt Lake area. She filed a complaint on behalf of the employees of Devkripa Vyapaar Pvt Ltd, Akhon Samaj, against their chairman Sudipta Sen. She alleged that they had not been paid salaries and accused Sen of 'fraud, cheating and criminal intimidation'. States her FIR (32/13): 'On 15/4/2013, we received an email regarding closure of operations and termination of our services with immediate effect and advised us to search for new jobs. He is the sole signatory of banking operations and has now become untraceable which we believe is with the express intention of defrauding and cheating us of our legitimate dues.'

Braving the Bad New World

13 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 62

National interest guides Modi as he navigates the Middle East conflict and the oil crisis

Arpita Ghosh's complaint also said that employees were receiving threatening calls. This first FIR has been the basis of investigations begun by the police of Saradha's financial affairs. "There are six cases that are being investigated by us at present," says Deputy Commissioner (detective department) Arnab Ghosh. "The first four cases relate to employees complaining about not receiving salaries and facing sudden retrenchment. The other two cases are against two specific companies—Saradha Tours and Travels and Saradha Realty India Pvt Ltd. In both cases, the complaints were [of] these firms collecting money from local people. We are basically investigating these cases filed under sections of cheating and misappropriation of funds."

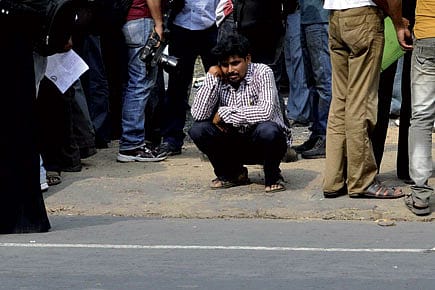

Outside Deputy Commissioner Ghosh's office sit a group of Saradha employees, waiting to 'assist' the probe. They have been taken in batches to their offices to help investigators locate files and account details that could help quantify the scale of the scam.

Among the nervous is Roy. He is hesitant to meet me, and when he finally agrees, he chooses the anonymity of a wooden bench under a peepal tree on a busy Kolkata footpath to recount the story of a financial crisis that has had echoes across West Bengal, Assam and Tripura after the Saradha chit-fund scam was busted.

Not very far from the Dhakoria Gol park branch office of the Saradha Group, where Roy deposited his collections, he begins haltingly with the fact that he comes from a family of bankers. "Both my father and brother worked in banks. So did I for 22 years, helping tea stall vendors, small shopkeepers and others save some of their earnings," he says. "The monthly salary of Rs 12,000 and 2-per cent bank commission was just not enough, not with the possibility of up to 20 per cent commission. Then it seemed like a necessity, now it seems like greed."

In March 2010, Roy was introduced to Saradha by a fellow agent. Like most others, he was impressed by the company's credentials, envious of the cars some of its bigger agents had been gifted, and taken in by its website description of itself as a 'kalpataru' (wishing tree) that was 'fulfilling dreams even in the recession stuck economy'.

Over the next three years, Roy sold schemes to 240 clients, mostly workers and shopkeepers in Burrabazar. He also convinced his father-in-law to invest Rs 4 lakh; he says he himself put in nearly Rs 20 lakh and introduced numerous people to the business who eventually became collection agents as well. "The last person I introduced was given a two lakh plus [roll] number. It shows you how many agents were out there on the streets, making collections."

Ghosh says there were 283,000 agents working for the firm in West Bengal alone. Founded in 2001, the Saradha Group had expanded rapidly. On last count, it had 150 companies operating in fields as diverse as real estate, operated travel agencies, media companies, malls, agro-based industries, livestock breeding and exports.

Saradha ran three schemes: a recurring deposit scheme, a monthly income scheme (MIS) and a fixed deposit scheme. While the recurring schemes running upto 5 years promised upto 15 per cent interest, the MIS ran upto 10 years promising Rs 2,000 per month for every lakh invested, and the fixed deposit ran for 14 years, promising Rs 10 lakh on maturity for every lakh invested. On maturity, investors also had the option of investing their returns in one of Saradha Realty's properties or going on a vacation abroad, both seen as ways to avoid coming under the scanner of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI).

In a report, SEBI has since stated that prima facie evidence indicates that 'under the scheme the real objective was to mobilise funds from the public by showing some real estate projects to investors and indirectly promising [the] return of funds with high interest rates'.

In Kakoli Dutta's two-room flat in Kolkata's New Ballygunj Road locality, Roy and a few other agents meet to discuss their options. They exchange stories of desperation, of angry investors threatening them with dire consequences, of personal financial losses, suicidal tendencies and of their 'stupidity'.

Jostling for space on the bed, Dutta says: "They made it look so glossy, so authentic that we brushed aside all our concerns. And when we heard [West Bengal's] transport minister Madan Mitra tell us to confidently invest in the Saradha group or were shown Mamata Banerjee's 'god bless you' note to Sudipta Sen, we felt buoyant. And then another Trinamool member Kunal Ghosh was running their TV channel. We felt that if members of the government are part of the conglomerate and are saying 'This is good', it must be good."

"There would be big agent meetings at stadiums and so many politicians would be there, sharing the dais with Sudipta Sen, praising his company," adds Roy. "They conned us and investors with their smooth talk and by showing off some of their projects."

For taxi driver Sanjay Jadhav, it was a simple choice. His uncle, an agent, had suggested Saradha's schemes. Jadhav thought it would help him save money to buy his own taxi. "I invested Rs 20,000 just seven months back, hoping to get Rs 66,000 after six years," he says. "I actually took it out of my bank and put it in this scheme. Now it's all gone."

Like Jadhav, thousands put in all they had in these schemes. From flower sellers, labourers and farmers to lawyers, housewives and doctors—everyone was saving up for a better future, a child's education, an upcoming wedding or old age. Across the state, there is news of despair, with three people already having committed suicide and hundreds of agents having locked their homes and disappeared.

The day Arpita Ghosh filed her FIR, another Saradha Group employee Debjani Mukherjee was at Jim Corbett National Park in faraway Uttarakhand with her boss Sudipta Sen. She had been travelling with him since 13 April and it was in the wilderness of Corbett that she apparently realised that she and her employer were on the run.

On a sheet of paper, folded innumerable times to fit into his shirt pocket, advocate Abhishek Mukherjee has jotted down details of the 10-day journey across states that his client took with Sen and another colleague to evade arrest.

Debjani Mukherjee, 27, who had joined the firm in 2008 and quickly rose to executive director level, has told investigators that she received an air ticket on her mobile from Sen and flew on 13 April to Delhi, where she stayed at a guest house in Vikaspuri. "She says she was told that a pending board meeting was going to be held and she was required to attend," the advocate says, sitting at the New Town police station where his client is being interrogated.

According to Debjani's statement, the next day, the four travelled to Dehradun, moving on to Haridwar on 15 April and Jim Corbett National Park a day later. "Debjani first suspected at Corbett that they were on the run," says advocate Mukherjee. "She had been aware of the crisis within the company and hadn't received any salary since November. She had even been asked not to come to office from 1 March. But Sen got in touch with her in April and took her along because he knew she knew too much. She is like a human computer."

The three were constantly on the move. On 17 April, they stayed at the Rubus hotel in Dhangari, Nepal, and then moved to Rudrapur in Uttarakhand for a night halt. They reached Sonipat in Haryana on the 18th. On 19 April, Mukherjee says that when the three stopped for lunch at a dhaba, Debjani managed to book an air ticket back to Kolkata from a nearby cyber café but couldn't use it. The journey continued through Himachal Pradesh, and, unable to reach Manali on 20 April due to bad weather, the three headed to Udhampur, near Jammu.

On 22 April, Mukherjee got a call from an unidentified number around 6.30 in the evening. It was Debjani calling from Sonmarg in Kashmir. "She had paid a waiter Rs 200 to be able to use his mobile. She called me and her mother," says Mukherjee. "She basically wanted to surrender."

Sudipta Sen, Debjani Mukherjee and Arvind Kumar Chauhan, a general manager of operations for Jharkhand, were arrested on 22 April by the Jammu & Kashmir Police and later send to Kolkata on transit remand. Manoj Nagel, director of the Tours and Travel firm, was picked up in Kolkata later. All four are in police custody till 8 May, when they will be produced in court again.

That they fled seemed to confirm fears that Saradha's schemes were Ponzi pyramids, which operate by using funds from a widening base of new investors to pay off older (and fewer) investors, and then proclaiming this as proof of their 'success' to attract even more money—or some variant thereof.

Even as investigators try to unearth the extent of the scam, it is clear that a lot of red flags raised periodically since 2010 were ignored by the state government, indicating a systemic failure to stop Sudipta Sen from collecting more deposits from unsuspecting investors right until a few days before he fled.

In April 2010, SEBI received a letter from the director of the Economic Offences Investigation Cell of West Bengal, stating that Saradha Realty India Ltd was collecting 'contributions of monies from the public particular in rural areas of the State of West Bengal'. The letter was accompanied by a brochure circulated by the company with details of its fund mobilisation methods in apparent violation of SEBI guidelines.

What followed was a series of exchanges between SEBI and Sen. All through 2010, SEBI sent numerous letters (3 June, 14 July, 13 August, 12 October and 3 November) asking Sen to submit documents related to the group's schemes and provide details of funds mobilised from investors under these and how they were being used. In response, Sen sent 'voluminous and irrelevant' information to SEBI's regional office in Kolkata, even as SEBI plodded on with its probe.

Meanwhile, in September 2011, Congress Member of Parliament from Malda AH Khan Chowdhury wrote a letter to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh expressing concern about Ponzi schemes being run in the state. "I was worried because I suddenly saw them flourishing, encouraged by the government," says Chowdhury, talking to Open from Malda. "It out has been a constant problem in the state with so many poor people losing everything. I had some idea about these various firms that were indulging in these schemes, promising unrealistic returns. I felt I had to do something."

Alarmed by that letter, Roy turned jittery for the first time since he began working as an agent for Saradha. "I slowed down my collections. This was the first time that agents were worried," he recalls. "But then Sudipta Sen called a meeting and assured us that things would be sorted out in a couple of days. The next thing we hear, the MP has written another letter, apologising for his allegations against Saradha. We were immediately back in business."

Every agent was given a copy of Chowdhury's second letter, written on 15 March 2012. In this one, he said that he had been mistaken about Saradha Realty India Ltd and was withdrawing his complaint. It was not involved in any chit fund or micro finance scheme, he added, and also said that he was mistaken in linking Sen with Sanchayani Savings and Investment Company Ltd, which went bust in the 1980s (just as Saradha now has).

Chowdhury has got a lot of flak for speaking up in favour of Saradha Realty. Clarifying, Chowdhury says: "I only spoke about Saradha Realty, not the other companies under the group. I still had my doubts."

But these doubts did not reach agents and investors who felt reassured that everything was okay with Saradha. IN 2011, TRINAMOOL Congress MP Somen Mitra had written to Prime Minister Manmohan Singh expressing concern about Ponzi schemes in West Bengal. "But we had no clue of anything and neither did our clients," says Roy. "There was no news about a probe being conducted or any warning [notice] telling us not to promote the companies' schemes. Nobody said anything. The only man advertising was Sudipta Sen and he pushed us to collect more. If we had the smallest inkling of what was going on, we would have stopped."

On 14 March 2013, just a month before the Saradha scam hit headlines, two Members of Parliament—the BJP's DB Chandre Gowde and the DMK's Adhi Sankar—raised a question on such dubious schemes in the Lok Sabha. In response, Union Minister of Corporate Affairs Sachin Pilot tabled a list of 182 companies against whom complaints had been received. Of these, 73 were based in West Bengal. The list includes 10 companies of the Saradha Group, including Saradha Realty India Ltd and Saradha Tours and Travels Pvt Ltd, the two companies now under the scanner. And yet, Roy managed to collect money from depositors even on 16 April, three days after Sen had fled and hours before news of the scam hit the streets.

In its 23 April 2013 order on the probe it started in 2010, SEBI has directed 'M/s Saradha Realty India Ltd and its Managing Director, Mr Sudipta Sen to wind up its existing collective investment schemes and refund the money collected by it under the schemes with returns which are due to the investors as per the terms of offer within a period of three months from the date of this order and submit a winding up and repayment report'.

But neither the order nor the present political flurry, not to mention the urgency to introduce a bill to protect investors against such schemes, seems to matter in Kakoli Dutta's cramped bedroom. "What is the point now?" rues Roy, as he does all he can to reassure investors on the phone. "Dheeraj dhariye (be patient)," he keeps mumbling.