We Are Murugan

Tamil writer Perumal Murugan has fallen on the point of his pen, following the fate of his own ill-fated characters. What can we do to bring him back?

Tamil writer Perumal Murugan has fallen on the point of his pen, following the fate of his own ill-fated characters. What can we do to bring him back?

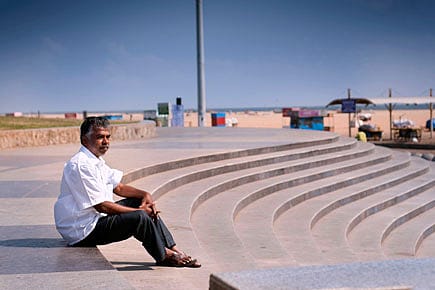

Unknown Object'He never could resist the desire to possess what attracted him', says Kali, the hero of acclaimed Tamil writer Perumal Murgan's novel One Part Woman (Penguin Books India, 2013; published in Tamil as Madhorubhagan in 2010), at the outset. 'He felt he should have left it on the tree. The sight of the flower on the tree was more beautiful than its scent.' A foreshadowing of the first fall of this Eden, echoed this week with the decision of its author to quit writing in what they are calling his literary suicide. Murugan could have been speaking about the nature of writing itself, today; what should we choose to leave on the tree, what is safe to try to pluck and understand?

Like others around the world, we in India have spent the last week expressing our outrage at the persecution of free speech, in the unfortunate violence that killed many staff members of dangerously satirical French weekly Charlie Hebdo last Wednesday, even while we debated what exactly it means to be able to say exactly what we want. When is it alright to offend someone, and when is it not?

Closer to home, this writer has thrown down his pen ahead of the battle—Murugan has been persecuted by Hindutva groups in his hometown of Tiruchengode, Tamil Nadu for three weeks over his fictitious representation of a fading local tradition which they fear suggests socially condoned licentiousness. A day after Murugan fled with his family on 8 January, the town seethed with protesters; on 26 December, an illegal assembly had burnt copies of his book, asking for the arrest of author and publisher, and, of course, burning books. Still under police protection after deciding to withdraw not just the offending book but his entire body of work, in what has been called his living death, he has thrown down the pen altogether—his Facebook page made the announcement which ricocheted around the literary world yesterday, and he has signed a statement to this effect, asking to withdraw his books.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

"He's extremely hurt. Murugan loves this place so much; he is prepared to give up his writing to live there. He is the most important writer of this generation to emerge from his region, and put it on the map," the publisher of Madhorubagan, Kalachuvadu's Kannan Sundaram said over the phone today from the Chennai Book Fair. Emotional and enraged like many of Murugan's supporters, like many, he is unable to act as yet; business must continue as usual, and, like everyone else in his industry, he must wait for the machine to speak. (Penguin Books India declined to comment, as of today.) "The statement he has signed has no legal binding, but it is morally binding, and we have been good friends for twenty years, so I will stop selling his books at my shop. As of now, all his books are available at the book fair and others may sell them [Murugan is also published in Tamil by Nattrinai, Adayalam, Malaigal and Kavalkavin]," he says, waiting to hear from a lawyer who is on the case. "There is hope yet, as due to the nature of publishing and distribution, books cannot be withdrawn so fast."

Was Murugan's harakiri an extreme measure? These are no ordinary times; no time, it seems, for half-measures, for compromise, which Murugan has reportedly tried, offering to take out offending passages from his novel. "He aspired to buy peace. In Tamil there is an expression: they say the animal who tastes blood will not stop," says historian and Tamil writer AR Venkatachalapathy, who wrote on Monday: 'The Sangh Parivar, seeking a toehold in Tamil Nadu, sensed an opportunity. A local Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh functionary was in the forefront of the assembly that burnt the book' (The Hindu, 12 January). We speak late into Tuesday night, and today he continues to comment widely; he has had a full day speaking for the silenced Murugan, who is declining to speak at the moment.

The author of four novels, three short story collections and three anthologies of poetry, Murugan has been a professor of Tamil for close to two decades, and has researched the folklore of his native Kongunadu in depth. He was intrigued by the unusual stories of 'Sami-pillais' (literally god children) birthed by women who visited the Ardhanareeswara temple of Tiruchengode during its annual three-day chariot festival. Hounded by their difficulty in conceiving, like the novel's heroine Ponna, the women were free to choose a stranger who god would choose to appear through, local custom has it; as Kali's mother tells him, 'Who is without lack in this world? The gods have made sure everyone lacks something or the other. But the same god has also given us ways to fill that lack.' This practice, discontinued for decades, is not surprising in any non-mainstream community around the world, as historians and anthropologists tell us; people in Tamil Nadu (and, indeed, other parts of India) have been known to have two spouses, out of practicality, or out of never having known their first intended, for example.

Which novelist would not have been drawn further into this world? I read One Part Woman at last this December, enjoying the lyrical, spare portrait of rural Tamil society, showing us what its people are like with the truths of fiction. It is at once a simple book and a rich one, showing us a rustic panorama of jungle hideouts –Kali's friend Muthu, Ponna is fond of laying away food and supplies in forgotten pits and comfy tree branches, where they rejoice, like little children– and village festivals, with room for eccentrics like Uncle Nallupayan (literally 'nice boy'), who vows he will never marry and tells Kali there is no need for him to have a child if he cannot, as life has lots else to offer. It is the perfect, blighted backdrop to the sweet and unusual relationship of Kala and Ponni, a couple who are utterly in love yet forced to take part in a foreign ritual founded in faith, unable to live in peace; they must produce a child to make up for what is seen as lacking, to satisfy society's own failings, in a curious inversion of propriety. (There are two sequels, with alternate endings.) Similarly, Murugan has vowed to do the very worst possible thing, out of a lack of options.

"This is the first time there has been a real groundswell of support," says Venkatachalapathy, who first brought Murugan's work to my attention years ago when I worked in publishing, with his powerful novel around a dalit farmhand, Seasons of the Palm (Tara Publishing, 2005). It was shortlisted for the Kiriyama Prize, and took him to international readers. "I think the tide has turned only after he declared that he is committing a literary suicide. We should pressurise the government into amending the wrongs done by the district administration."

I ask him what he means when he says, at one point, "Tamil writers are a sack of potatoes", and he elaborates; "They are a fractious lot, riven by jealousies and pettiness. Sorry that's the truth!" True of almost every literary community, perhaps, and here is a good time to make an exception.

We are almost bored of outrage. We have seen writers spend years traipsing through courts to defend sex scenes hardly vigorous enough to be offensive in the first place; writers compromising even while writing, to avoid public scrutiny; writers persecuted for books that may not have been literarily worthwhile, but have every right to be out there. As we continue to buy his book, read from it, give it room at readings, we must give Murugan strength to rescind his decision, and buy him protection from the mob; for, it is to be argued that Murugan was coerced into making this decision. There may yet be an alternate ending. Like the sapling that blooms into a large portia tree which shades Ponna's family home and provides it with unanticipated bounties, Murugan's novel surprises the reader by mining small-town Tamil Nadu to provide real strengths. Let us not allow its flowering to have been in vain.