The Lokpal and You

A look at how differing proposals to fight corruption will actually work for the harried citizen

Mihir Srivastava

Mihir Srivastava

Mihir Srivastava

|

15 Dec, 2011

Mihir Srivastava

|

15 Dec, 2011

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/lokpal-you.jpg)

A look at how differing proposals to fight corruption will actually work for the harried citizen

As Open goes to press, we have three alternate versions of the Lokpal Bill before us. One, of course, is the one proposed by Team Anna, the Jan Lokpal bill; the other is also a Civil Society version drafted by the National Campaign for Peoples’ Right to Information (NCPRI); and the third is now the consensus Lokpal

Bill agreed upon by India’s ruling United Progressive Alliance (UPA) after the Standing Committee set up for the purpose submitted its report. It is worthwhile at this juncture to juxtapose this official version against how things stand now.

For far too long have the provisions of the Bill been debated in the abstract. There has been too much grandstanding about how a particular provision could dilute or strengthen the Bill, but there has been almost no understanding of how any of it will actually play out and affect the life of an ordinary person.

Here we consider some real-world scenarios of corruption and lead you through the proposed remedial process once the legislation is enacted and Lokpal instituted. They range from high corruption such as seen in the 2G case to the kind of corruption almost every Indian deals with in day-to-day life.

How a law actually works on the ground can be very different from the rarefied arguments we often hear on TV channels or read in newspapers. Keep these scenarios in mind as you watch the debate unfold in Parliament. The real question is not whether a particular group of officials is within the purview of the Bill or not, it is whether the law that is enacted can have a real impact on your life. This Bill will affect every citizen, and whatever version is finally put in place will assuredly be better than the current reality, but whether it works for you depends on how particular provisions come to bear on specific cases.

SCENARIO I: THE PATWARI

Given the criticism that Anna Hazare’s movement against corruption is largely an urban middle-class phenomenon, it is best to begin by considering a scenario commonly encountered by India’s vast rural majority: say, a patwari (a Group C or D official depending on seniority) in Begusarai district of Bihar demands a bribe of a farmer to carry out proper measurements of a plot of agricultural land (many of the arguments here also apply to a lower-lever policeman asking for a bribe).

Under the present set-up, there is no effective way to deal with this problem, and the farmer would have to pay the bribe. Technically, in states where a lokayukta has been appointed, a complaint could be registered, but in practice, there is no way to ensure it is acted upon.

The UPA version

The Government has proposed a Grievance Redressal Bill that codifies a legally-binding citizens’ charter and imposes a mandatory timeframe to ensure that the work is carried out. The aggrieved farmer will have to appeal to the head of the revenue department at the district headquarters—the district magistrate or additional district magistrate, revenue. There is no provision for the imposition of fines on a patwari if a delay in providing services is found to be deliberate or because of neglect. If the patwari is senior enough, s/he could be a Group C officer and thus under the likely coverage of the UPA’s Lokpal Bill, but the Government has yet to clarify how exactly the mechanism will work.

Team Anna’s proposal

It’s twofold. One is investigative. The Lokpal would have an office/police station in each district of India, and lokayukta one such in each block of the state under his/her charge. For corruption in a Central Government department, you could register an FIR at the Lokpal police station in your district, and for corruption in a state government, you could register such a report at the lokayukta police station in your block.

The second is a grievance redressal mechanism: each department will have a citizens’ charter that fixes specific timeframes to address problems, with the added provision of compensation to the farmer—paid from a fine imposed on the patwari if he fails to address the problem within the stipulated time period. In the plot-measurement case under consideration, it is this provision that is likely to be invoked. In theory, the farmer could go file a report with the block’s lokayukta police station, but it is difficult to imagine a police party arriving and attempting to nab a patwari in such a setting.

The NCPRI model

This does not envisage any Lokpal or lokayukta intervention at this level. Every department will have a grievance redressal officer (GRO) to receive and deal with complaints within 15 days (48 hours in case of urgent grievances). The farmer can approach the GRO of the revenue department of the district; if no action is taken within the pre-set timeframe, he can make a parallel appeal to an independent district Grievance Redressal Authority and district magistrate. To initiate criminal action against the patwari, he needs to lodge a complaint with the local police station; if no action is taken, he can appeal to the block’s lokayukta police station.

Our verdict

Most cases of petty corruption can be effectively sorted out through a grievance redressal mechanism that imposes time limits.

SCENARIO II: THE POLICE

A police constable in Delhi demands a bribe for your address verification for the issuance of a passport.

The UPA version

Under it, the matter will be first taken up by the Delhi government’s Anti-Corruption Branch (ACB). Then, there is the Delhi Police’s inhouse—and acutely understaffed—vigilance department. Neither the ACB nor this department has been keen to tackle such offences, on past experience. But then, there is the proposed grievance redressal mechanism, which features a citizens’ charter plus an information-cum-facilitation centre within Delhi Police to ensure that grievances are systematically recorded and tracked using telephones, mobile text messages and the internet. You will have to approach the department’s grievance redressal officer; if no action is taken, you can go to the commissioner of police or head-of-department. This would be impractical, given how hard it is to access a police commissioner.

Team Anna’s proposal

Your complaint will be registered at the Lokpal police station, which would be independent of the Delhi Police and empowered to entrap and take action against the corrupt constable. Even the grievance redressal mechanism would be beyond the Delhi Police’s control, under supervision instead of the district Lokpal police station. Your address verification would need to be done within a preset timeframe, beyond which a daily fine would be imposed on the errant constable for any unexplained delay. This is an effective deterrent. The RTI experience is that in 40 per cent of urban cases and 30 per cent of rural ones, official work gets done as soon as an RTI query is received. In this case, the response is likely to be faster, given the financial penalty.

The NCPRI model

You complain first to the local police station. If no action is taken, you go to the district Lokpal police station. If you seek grievance redressal, the matter will go to the concerned department with a specified timeframe for action and provisions for punitive action. Unlike the UPA Bill, the NCPRI proposal allows for a ‘no action’ appeal to the redressal authority, run by an independent district level officer, if you’re left dangling.

Our Verdict

In such cases, far more than policing, it is the grievance redressal mechanism that will resolve the matter. In this context, the Grievance Redressal Bill cleared by the Cabinet is highly unsatisfactory, and ought to attract far more attention. In day-to-day problems, this is what will matter, and so it should include an independent redressal mechanism, clear timeframes for task completion and the possibility of punitive measures.

SCENARIO III: THE PROPERTY REGISTRAR

Say, a Group C revenue functionary of the state government demands a bribe to register a house you have bought in an ‘all-white deal’, with all payments made to the seller by cheque.

The UPA version

Such matters involving a Group C employee can be referred to the state’s lokayukta appointed under the Lokpal Bill. The mechanism by which such employees are to be policed, however, is still not clear at this point. The Government also proposes a departmental GRO answerable to the head-of-department—in this case, the district magistrate—who may well be sharing the bribery spoils. Since there is no provision for the imposition of fines, the toughest ‘action’ you can hope for is a show-cause notice being issued against the corrupt functionary.

Team Anna’s proposal

Your complaint will go to the district’s lokayukta police station, which will first try to entrap the official while taking the bribe, and then issue him/her a show-cause notice—all within the timeframe of the citizen’s charter. There are provisions for penalising the official, which could be used to compensate you for the delay. There is no conflict of interest, as the entity resolving your problem is independent of the revenue administration. Team Anna’s proposal does have one hitch: every block has a lokayukta police station, but there is only one Lokpal police station in every district to deal with Central employees. A problem involving, say, your pension funds held at the postal department, would require a visit to the district headquarters.

The NCPRI model

This speaks of ‘territorial jurisdiction’ where you must first approach the local police station to complain. If this does not work, you go to the lokayukta police station. You can expect a time-bound response, even as a show-cause notice is issued to the local police station for its failure to register your initial complaint or take any action. Non-compliance can then be reported to the supervising authority—the state or central vigilance commissioner in case of Group C employees, and the Lokpal or lokayukta in case of higher officials of the Central or state government, respectively.

You can also seek help from the GRO in the revenue department (beyond the lokayukta’s control in this case), who is empowered to impose fines on the corrupt clerk, with the amount calculated on a daily basis depending on the delay in terms of number of days; if no action is taken, you can appeal to the Grievance Redressal Authority or district magistrate.

Our Verdict

There seems no easy way out in such cases. The bureaucratic machinery set up under Team Anna’s proposal is formidable, but even so, cases of Group C corruption would seem better addressed by this than the NCPRI proposal, which places hope in the local police station (where lodging an FIR is a nightmare) as a first resort, though with the option of appealing to the state’s lokayukta (for property registration) or country’s Lokpal or Central Vigilance Commission (CVC) if the case involves a Central government employee.

SCENARIO IV: THE BUREAUCRAT

Say, a joint secretary in the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways rigs a Rs 2,500 crore tender to build a 174 km highway from Nagpur in Maharashtra, to Betul in Madhya Pradesh.

Right now, such cases are almost impossible to pursue, with the Government usually denying the CBI permission to either investigate the case or prosecute the culprit/s.

The UPA version

The CBI can initiate an investigation with the Lokpal’s nod, a major improvement over the past. But since the agency’s administrative control will remain vested in the Government, it will be difficult to move against the bureaucrat if s/he is shielded by the political leadership, especially if the ministry/cabinet’s own acts of omission have a bearing on the case. The CBI can decide not to act for years together, and even if it does so, the judicial process can be very slow. As of 30 June 2011, there were 2,272 CBI cases pending in various courts at trial stage for more than 10 years. That’s enough time for the road project to get done, money to exchange hands, and the bureaucrat to retire rich.

Team Anna’s proposal

The CBI would be independent of the Government. Pre-set timelines would mean quicker investigation and prosecution. The CBI would be under performance pressure, thanks to the Lokpal’s supervision, as also public scrutiny, given that all documents related to the case would be made public once the investigation is complete.

The NCPRI model

This does not differ in substance from Team Anna’s in the specifics, but since only Group A and B cases will be taken up by the Lokpal, individual cases would be paid greater attention.

Our Verdict

The inclusion of Group C employees, who form over 60 per cent of all Central Government employees, under the Lokpal under the UPA proposal and Team Anna bill would inevitably mean enormous amounts of extra work in tackling corruption. This would be so even if only a small fraction of all Group C cases are taken to the central body. Under the NCPRI version, however, such cases would be far more closely supervised.

In all, what India deserves is a balance of pragmatism and efficacy, a balance yet to be struck.

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

MOst Popular

3

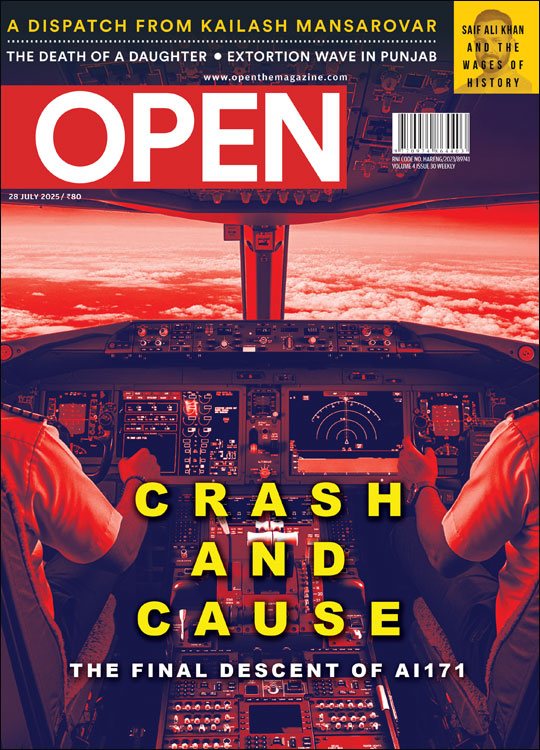

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba