The Capital City

Mumbai has its commercial roots in drug money. A profile of the City

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

Madhavankutty Pillai

|

16 Oct, 2014

|

16 Oct, 2014

/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Capitalcity1.jpg)

Mumbai has its commercial roots in drug money. A profile of the City

Just as one crosses the suburbs into Worli, Samudra Mahal juts up from the edge of Mumbai, casting its eye out into the Arabian Sea. It is one of those multi-storeyed buildings that go by the moniker of ‘landmark property’. A flat is an expensive thing to buy in the city anywhere. In south Mumbai, the prices are obscene and beyond the means of most Indians. But properties like Samudra Mahal set records. Last year, the company Borosil bought an apartment there paying around Rs 1.2 lakh per square foot; total cost: Rs 43 crore.

A few years ago a family too bought a flat there paying a huge sum and then moved in. Money can’t buy you happiness but you do expect it to take care of the petty problems that bedevil the middle-class and the poor. A few months into living there, the geyser burst, pouring down 20 litres of water. While renovations were ongoing, they looked at the work that the contractor had done and saw cupboards and cabinets but without drawers inside. He wanted more money than what had been agreed upon and this was his way of holding them to ransom. The walls seeped water in the monsoon, the servants quit without warning, and so on. Last Friday, the taps stopped running for two hours in the morning because the tanker had got delayed—there was no 24-hour water supply in Samudra Mahal and the society has to buy it. Moral of story: Rs 43 crore can get you the best address in town, but not the best lifestyle. “The address does not buy you peace of mind, no address in Bombay does,” says the resident. “The only thing that makes Samudra Mahal special is the price. Property prices have got nothing to do with the quality of the space that you are getting.”

In some sense, that is an egalitarian quality of the city; no matter how wealthy a personis, Mumbai— infrastructurally battered through and through— ensures discomfort. But incredible amounts of money still float around and the rich live a schizophrenic existenceof opulence and pettiness. “There was a wedding last year where Housie was being played and they gave away yachts. I know people who will only shop abroad for their kids.

They will not feed them any snacks that are locally made because they think it is not good for health— a ridiculous view of child rearing. At the same time, when they are out shopping, they will look for a discount on every purchase they make,” says the resident.

Hurun report, an international luxury publishing and events group, comes out with list every year of the richest people in countries around the world. Last month, it released its India Rich List 2014, giving an idea of how Mumbai remains the cash cow of the country. According to it, the wealthiest man in the country— Mukesh Ambani with a personal net worth of Rs 1,65,000 crore was from Mumbai. The second richest man was also from there and that was Sun Pharma’s Dilip Shanghvi with Rs 1,29,000 crore. Of the 10 richest men in India, four are from Mumbai, the other two being Pallonji Mistry and Kumar Mangalam Birla.

To make it to the India Rich List, the cut-off was Rs 1,800 crore and there were 70 such individuals from Mumbai (Delhi was a far second with 37). ‘Whilst Mumbai continues to dominate with 30% of the list residing there, Delhi came in second with 16%, followed by Bangalore with 10%,’ the report noted. The country’s most valuable company, Tata Sons, is headquartered in Mumbai with a valuation of around Rs 6 lakh crore.

A few months ago, the real estate consultancy Knight Frank also published its annual Wealth Report. An Ultra High Net Worth Individuals (UHNWI), according to its definition, is someone whose net worth is worth more than $30 million, and it found that Mumbai had 577 such people in 2013. The number is tipped to more than double and go up to 1,302 in ten years. It is a city of ever increasing millionaires.

Mumbai’s association with wealth has always been a progression. There are the old rich who are joined by a wave of new rich with a new set of economic conditions. For example, the Punjabis and Sindhis who came after Partition and then slogged their way to prosperity. Then they soon became the old rich as another wave arrived. The only thing common to all of them is what is common to all businessmen—competence, ambition and a degree of amorality.

The first such wave of the ultra wealthy came to the fore right in the early nineteenth century and what they got into would today be a questionable sector (though of course it is foolish to look at a different age using the morality of today). Mumbai has its commercial roots in drug money. In his book Opium City: The Making of Early Victorian Bombay, Amar Farooqui writes, ‘Its transformation into one of the leading cities of the empire occurred fairly rapidly within the space of about four decades during the first half of the nineteenth century. Circa 1800- 1840 Bombay became a major exporter of opium and raw cotton, mainly to China. The role played by these two commodities in the rise of Bombay and its capitalist class is generally recognized, but the centrality of opium has not been sufficiently emphasised.’

For example, the community of Parsis, known for their honesty and charity, thrived on opium in that era. They began as ship builders for European clients in Gujarat. The historian Gyan Prakash writes in his book Mumbai Fables, ‘When the Company (East India) shifted its headquarters to Bombay, they followed and quickly became the most important and wealthy mercantile community. They were not alone. Hindu and Jain merchants of the Bania caste and Muslims of the Bohra, Khoja, and Memon communities from Gujarat flocked to exploit the opportunities that the new colonial settlement offered.’ When the British encouraged opium trade with China from Mumbai and the traders of these communities saw the profit to be made, they didn’t need to think twice.

Rafique Baghdadi, an amateur historian and an expert of sorts on all things cultural in Mumbai, says that Parsis also had the idea of living it up. He says even now if you go to any of their houses built in that time, you will notice how modern and aesthetic they were. “They were using the latest lighting equipment in their homes. They were entertaining people. They were trading. They were globalising, especially because they were trading with China,” he says.

Since then there have been periodic changes in the social composition of the wealthy in Mumbai. Dwijendra Tripathi, a former IIM professor who is India’s foremost business historian, says that in recent times the most visible change is the emergence of Marwaris and Punjabi Khatris on the Mumbai business scene in a big way. “They, of course, are not new entrants, but have carved out a more dominant position in recent years,” he says.

There have been those who couldn’t adapt too, like the former textile barons. “Business groups like Mafatlal that remained stuck to the past even after liberalisation brought to the fore new business opportunities had to suffer. Family divisions also added to their woes, but as the Aditya Birla Group has shown, the consequences of family splits can be overcome by prudent policies and initiatives,” says Tripathi.

Rafeeq Ellias, an award winning filmmaker, photographer and long time chronicler of many aspects of Mumbai, explains the socio-economic status of the city’s inhabitants with respect to their position vis-a- vis the suburban railway tracks. In 1974, when he left for Japan for a long stint abroad, he remembers that status altered downwards as “you went from the western side of the tracks (Marine Drive, Malabar Hill, Worli) to the eastern side (Bombay Central, Byculla, the docks on Reay Road), from the western railway to central to the harbour line. And of course it altered similarly as you went south to north, from Churchgate to Andheri then.”

When he returned in 1979, he found it still a city holding on to its cosmopolitanism, its relative inclusiveness, its ability to absorb people from all parts of the country, its shyness in flaunting wealth. “But that reticence in flaunting wealth began disappearing as the city’s textile mills closed down and a new ‘economic order’ began making its impact. Over the years, the city began re-configuring itself. The mills were replaced by shopping malls. New residential projects proudly describing themselves as ‘gated colonies’, oblivious to apartheid connotations of South Africa, began springing up in what was once the city’s underbelly. Parel, Lalbaug, Wadala for example,” he says.

He also observed that with wealth came callousness towards the environment, public spaces, public health, education and transport. “The wealthy in developed countries have their own complexities but they have realised, even if partially and selfishly, that the greater good is, in the final analysis, often also in their interest. Which is why New York has many times more tree cover than Bombay, even tiny Taipei has open public spaces that even distant suburbs in Bombay do not have. Pollution levels in these cities have actually declined. [For] the wealthy in Bombay on the other hand, everything is fine so long as they can travel from air-conditioned homes through air-conditioned cars to air-conditioned offices or gyms and back to their residential towers; 200 metres is too much to walk,” he says.

And then there is the disappearing frugality that was once the hallmark of the business class, of an older generation of Marwaris and Banias. “That frugality came out of their experience of hardship back in their former villages or towns, of migration, of the many reminders of wealth being transient; it also coincided with Gandhian values and the shortages that were part of Nehruvian socialism,” says Ellias. He thinks that globalisation and the impact of media have made younger generation brash and eager consumers. They are the beneficiaries of the new economic order, of the financial and services industries, often earning dollar-equivalent salaries and perks. “They do not have the default anxieties of their parents who believed in owning their own apartments, in paying the minimum in taxes and maintenance, in savings for a rainy day. They are happy to pay high leases or steep maintenance fees even if they own their own apartments in their housing complexes,” he says.

Dwijendra Tripathi too observes, “Frugality has been one of the fundamental traits of trading classes all over the world. The trading groups of Mumbai retained this trait even after they pioneered modern industries. I think that most of the later generations are indulging in conspicuous consumption which has proved to be a characteristic trait of the neo-rich.”

A South Mumbai resident whose job brings her into contact with some of the wealthiest in that part of town has an interesting observation to make of investment bankers: whenever their bonuses arrive, they go and buy watches. “A watch can be as expensive as Rs 20 to 25 lakh. Young finance guys are all spending money on watches. They feel like it is the cool thing to do, a way of showing you have credibility as a rich person,” she says.

Given that it is hard to spend beyond a point, the biggest thing that people splurge on would have to be related to their homes. A budget of Rs 20 crore for the interior decoration of a newly purchased home wouldn’t be unusual. To a middle-class person, that is unimaginable but it is easy to ratchet up such a bill because all of it is imported. “If you buy a certain kind of sofas from certain kind of places, it can cost you Rs 25 lakh. A kitchen will easily cost a crore,” she says.

But she still thinks the nouveau riche who worked for their money have more character than the old who got it through inheritance. She speaks of landlords who own four or five flats whose net value would be over Rs 100 crore but will still give the bill of a painting job to a new tenant. “They are stingy and petty. They have no feeling towards it. If you spend money and buy a place you feel connected. If you have simply inherited [property], you have no connection. Their children will feel even less connected. They look at a home that they have inherited and given on rent and all they see is just cash,” she says.

Another set are those who might own a flat that makes them wealthy on paper but they don’t really have anything beyond that and so they become hostage to that real estate. Three or four generations stay together in small 2BHKs and the children refuse to move to a suburb where they can have a better lifestyle. Likewise, in a similar situation are many socialites who actuly don’t have too much money. “They are well connected, a lot of them are from the old families, but don’t have real money to spend. At least a large percentage of them don’t. But they all turn up for everything and expect all things for free,” she says.

To make the irony of that society even greater, when a finance professional or a successful entrepreneur rents a flat on Marine Drive paying a couple of lakh as monthly rent or buys it paying Rs 10 to 20 crore, he finds he has a neighbour who is paying a few hundred rupees as rent for a similar flat because the rates were frozen for those who became tenants decades ago thanks to obsolete laws. A lot of people in south Mumbai pay a pittance to live in some of the most expensive real estate in India.

An interesting aspect about Mumbai’s relationship with wealth is how the poor themselves have been co-opted into this culture. When a mall comes up over a mill, even prices of homes in slums rise. Ellias has made two films on Mumbai’s slum dwellers, one in the 80s and the other in 2005. “In the 80s, there was a strong politicisation, a greater belief in the collective struggle for dignity. 20 years later, I could see the impact of globalisation at the lowest levels of society. Slums were not impervious to the ‘steroid’ driven, heady rise in property prices. Which probably explains why slum dwellers can accept a glittering shopping mall or residential tower in their midst, something unimaginable in the 70s or 80s. So I would say that a slum dweller in the 70s saw the wealthy as a polar opposite at best, if not an adversary at worst. He now buys into the ‘mantra’ of growth, a version of the locomotive theory, if you will, that they will eventually also be beneficiaries. That has changed the way they look at the rich; which can of course change dramatically and unpleasantly if the economy doesn’t deliver.”

The trickle down happens because the support system for the wealthy is that relentless influx of migrant workers into Mumbai at every level. For example, a domestic servant in Samudra Mahal soon realises his or her market value and jumps ship. Drivers are now getting paid triple of what they got five years ago. The demand for their services comes from people with enterprise, entrepreneurs with ambition who have been the oxygen to Mumbai’s life-blood.

If you go to supermarkets in Mumbai, you will notice a prominent brand of dairy items called D’lecta. Deepak Jain, who started the company, came to Mumbai 20 years ago, first working in a dairy company and then branching out on his own in 2001. Mumbai, he found, was much more cool about money. People displayed wealth in far less conspicuous ways than they did in north India. He saw some very wealthy people going about in a very humble manner, people were less pushy about who they knew and who they were.

Jain started with very little capital, about Rs 10 lakh, and began D’lecta as a company marketing and distributing ghee for another company. “We established that as a brand. Along the way we learnt a lot about consumer distribution. For us, the initial three, four years were very challenging. I started with 8 to 10 people and there were months when I would wonder where the next month’s salary would come from,” he says. Right now D’lecta employs 125 people but, while his business has taken off, Jain says that his lifestyle continues to remain the same.

“I don’t think I am driven by acquisition of a wealth target. What drives me is the creation of something that I am proud of, a business which deals with good products, building some brands, influencing lives of people who work with us or are around us,” he says. Jain comes from a traditional business family with all their ethos of watching your pennies, but he notices the young earning a lot and spending a lot. “I am now 54, maybe my generation is not so much into it. People want bigger cars, better houses,” he says. This is the pool in Mumbai from which he draws those professionals who work for him. Both cultures, extravagance and moderation, go together in Mumbai, at least for the time being. Jain says, “For anyone who has some dreams, Mumbai is a very good place to start.”

About The Author

CURRENT ISSUE

MOst Popular

3

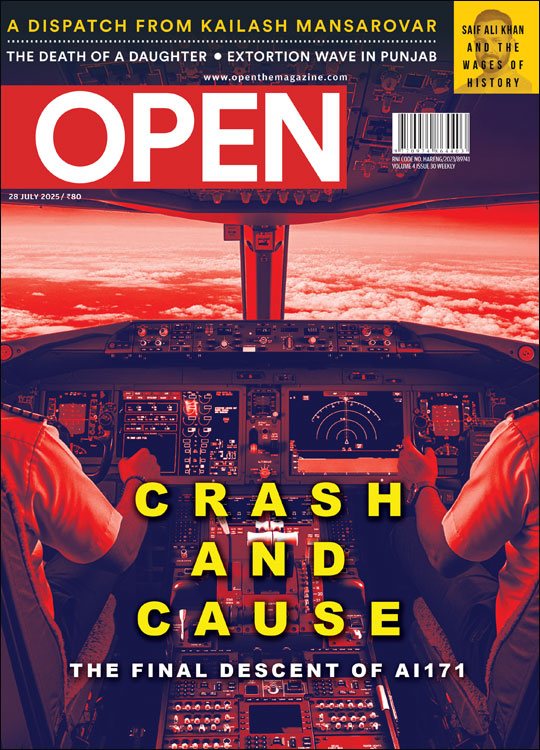

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover_Crashcause.jpg)

More Columns

Bihar: On the Road to Progress Open Avenues

The Bihar Model: Balancing Governance, Growth and Inclusion Open Avenues

Caution: Contents May Be Delicious V Shoba