Rohith Vemula: A Mind Torn Apart

Growing up in an SC colony in Guntur, Andhra Pradesh, Raja Chaitanya Kumar Vemula would often interrupt his mother at her tailoring machine and demand to know why he had to go to a government school when his elder brother Rohith, or Babji as he was addressed at home, had the privilege of attending an English- medium private institution. "Because there are more holidays in government schools," Radhika would say, to perk him up. He knew the real reason, of course. Rohith was the sort of boy who seemed destined for greatness—made of the stardust of tomorrow— while he and his sister were "average kids". The family, dependant solely on Radhika's daily wages of about Rs 150, could barely afford a good education for one child. "On most days, the headmaster fed him. Our neighbours donated money. We managed to keep him in school, sacrificing everything else," Raja says. "Mother and I dreamed that he would grow up to be an IAS officer, earning the respect of the world, surrounded by policemen hanging on to his every word." On 18 January, when a posse of police cars escorted his brother's body to a private funeral at the Amberpet crematorium in Hyderabad, Raja wept uncontrollably. His first thought was that his dream had come true—and how sorry he was.

We meet in the quiet, latticed corridors of Hyderabad Central University's (HCU) Health Centre, a short, welcome walk away from the shopping complex where a state of moral panic reigns, a week after Rohith Chakravarthi Vemula, 27, ended his life, following his, and four others', suspension and eviction from the hostel. The five men, Dalits and active members of the Ambedkar Students' Association (ASA), had been branded extremists and anti-nationals, and action demanded against them, in an outrageous letter to Union HRD Minister Smriti Irani that Union Minister for Labour and Employment Bandaru Dattatreya nonchalantly shot off. Allowed to attend classes but barred from public spaces in the university, their stipend withheld for months, the students began a hunger protest against the 'social boycott'. It had all started with a demonstration against the death penalty awarded to Yakub Memon, followed by a scuffle with the ABVP over its disruption of the screening of Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai, a documentary on communal riots, at Delhi University. From charges of indiscipline on campus, the matter had quickly snowballed into allegations of 'anti-nationalism' against the ASA members. Now they wanted the eviction revoked and the authorities responsible for this gross over-reaction brought to book.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

This movement for justice has found in Rohith's death the martyr it inwardly sought. Rohith may have counted on his suicide becoming the last word of consequence in a protracted battle for Dalit students' rights—the suspension has been revoked, help promised to his family and Vice-Chancellor P Appa Rao sent off on leave—but would he have condoned the kind of raucous electioneering that has ensued? The Congress, the Aam Aadmi Party and the Left parties have coiled around him, fashioning from his remains a power tool to wield against the ruling BJP. With their moralising reductionism, they have liquefied the humanity of Rohith to a watery soup of caste. Now, a fortnight since he passed, we can finally look beyond the distractions from the tragedy of a young man's suicide at why he suddenly became allergic to hope.

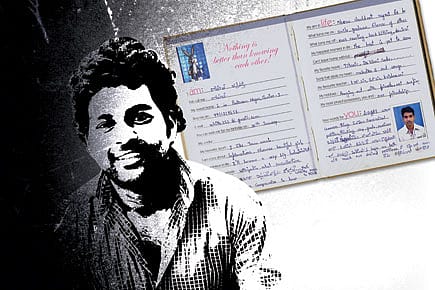

Rohith Vemula lived many lives, like the Joycean alter ego Stephen Dedalus, or Malcolm X, whom he was so fond of quoting. It was a breathless dash from one reality to the next spasm of inspiration, and he constantly updated himself, broke free of his surroundings, and came to the realisation that there was infinitely more to him than the identity he was born with. He was the aspiring science writer—from his eloquent suicide note—but he also had serious entrepreneurial ambitions ranging from granite quarrying to mushroom farming. Information and beautiful girls were what he was 'crazy about', he wrote in a delicate, rounded hand in a dear friend's scrapbook in 2009. Yet, towards the end, he brushed aside the thought of marriage when his mother brought it up. He had dreaded losing the friends who sought him out in the depths of sleepless nights, but he finally withdrew into himself, keeping up the pretence of socialising while the rooms of his mind were locked out of sight. What made him spiral down his personal abyss? Was it the Dalit experience on campus, the asymmetry of life as a first-generation university student living stipend to stipend? Did he fancy himself an icon of the Ambedkarite movement? These are but bowlderised versions of one man's struggle through the maze of friendships, love, politics and identity.

"Rohith was not worried about his future. He had few possessions, not even a computer. 'If not a PhD, something else awaits,' he would tell me," G Umamaheshwara Rao, a Political Science scholar in whose room Rohith hanged himself. Rohith does not seem to have believed that his life story was the story of his community. That is how he could bring himself to betray his future. He was, first and foremost, an eager explorer of his self, raiding the traditions of Western philosophy and Indian political thought with intellectual ferocity. His existential angst stemmed from his persistent quest for purpose in an unequal world. Acutely sensitive to alienation, he watched people suffer, not just victims of discrimination but of social evanescence in an unfamiliar urban setting. Political protests offered some respite and he became the 'rising star' of Leftist student group SFI, writing up radical posters and addressing gatherings with a conviction belying his age. But the idealist in him felt ethically culpable for aligning with an organisation that fell short of being truly classless. At the ASA, he was the born-again Dalit, making amends, surrounding himself almost always with friends from his community of Malas, talking the politics of exclusion to the exclusion of everything else. Desperate to make up for lost time, he was also paring himself down to the one identity he would be remembered by: a Dalit.

In the gauzy light of the morning, pictures of Rohith hang from branches like Christmas ornaments. Under a tent, students continuing the hunger strike he began stir in their blankets. In a short while, TV news crews will descend on this overworked theatre of protest and spout borrowed words of wounded rage. The victim will be sainted all over again, under the light of a giant white star beaming atop a building, symbolising his rise from 'the shadows to the stars'. In life, Rohith was a guiding star for dozens of men and women who found themselves alone in the campus, says Sunkanna Velpula, a PhD Philosophy student and ASA leader who is among the condemned five. In this convergence of strangers, first-generation students hailing from villages struggle to find a foothold, he says. The son of Dalit agriculturists in a small village in Kurnool district, Andhra Pradesh, Velpula came to Hyderabad brandishing his BEd, only to be turned down by city schools. "I had studied in Telugu medium. I could not speak a word of English. So I worked as a bodyguard, drove an autorickshaw and played small roles in six Telugu films before making the switch to academic life," he says. The struggle was not over. Here he found himself a fiddler on the roof, trying to make sense of a foreign language, to not stare at girls in short skirts for fear of being branded a 'rapist', to assimilate into the mainstream. "In the village, when my father told me to stay away from the main street, I did not think to question him. In the university, I could finally imagine a different future, but I was heartbroken at the same time that it wasn't all that different. An outcast back home, I was also an outsider in the city," Velpula says.

When Velpula arrived at HCU a decade ago, almost half the Dalit students were of rural stock. Today, he says, a majority are urban. "A group is disappearing from campus and this is creating big gaps. Most Dalit women, for instance, hail from urban centres and do not care to be seen with rural Dalit boys," he says. Upward mobility, a strong career focus and different political priorities— Dalit rights on campus versus reacting to national issues, for instance—are widening the trust deficit among the 800-odd Dalit students. "At HCU, we make friends but keep a safe distance. The ASA may make us feel like kin, but few of us are willing to reveal our deepest insecurities to our comrades," Velpula says.

We sit on a boulder, far from the cacophony of drums extolling Rohith's sacrifice, and wonder if he was a casualty of this fault line. Over the past few months, Rohith had become an aggressive leader; some say he insisted on being an office bearer for the second consecutive term— former vice-president of the ASA, he was once again elected joint secretary in December 2015—at the cost of lagging behind in academics. Most of Rohith's 'friends' at the HCU campus who spoke to me said their conversations with him rarely strayed beyond student politics or intellectual ruminations on Ambedkar. He was a man of few spoken words and many opinions, some of which he liked to air on Facebook. Only Rupa Murala, a former ASA general secretary, remembers him as a naturalist who knew every trail in the 2,300-acre sprawl of the campus in Gachibowli. "On Sundays, he would take a select few friends on hikes. We would go fishing, and he would know the scientific name of every fish," she says.

Science had fascinated him for much of his life. He graduated from Hindu College, Guntur, with 76 per cent in his BSc (Microbiology, Biotechnology, Chemistry) before joining HCU in 2010 to pursue MSc in Animal Biotechnology. With a CGPA of 7.8/10, he seems to have briefly mulled over moving to Bangalore for work, but the heady political environment at the university tugged at the rebel in him. He had already cleared the CSIR-UGC eligibility test for a Junior Research Fellowship and he resigned himself to subsisting on a stipend of Rs 25,000, even sending much of the money home. A PhD in Animal Sciences, however, made him a lab rat, thus limiting his involvement in politics. For Rohith, this was an unacceptable compromise. Within the year, he gave up his dream of disciplinary excellence to pursue research in the social sciences instead. When a classmate suggested he move out of the campus to save on rent—non-resident scholars get a monthly stipend of Rs 33,000—Rohith told him that he wanted to be in the political arena that was HCU. "This politics, it consumed him. The past two years, he hasn't been himself," says Sairam Narra, Rohith's classmate from undergraduate school and a close friend who is now an HR executive in Bangalore. He wants to remember Rohith as the boy who found happiness working after college hours at a juice stall near the Guntur bus stand, earning Rs 100-150 a day. "He had dreams. He did not want to work under anyone, so we had plans of eventually starting a business together along with two other friends. Rohith had so many ideas—mushroom farming, granite quarrying, a petrol pump. The last time we spoke, about 20 days ago, he assured me that he was done with HCU, that he would be ready to start up after sorting out his problems at the university," Narra says.

Unfortunately, Rohith kept his 'problems' cordoned away like exotic animals, although he never failed to help a brother, says Murala. About four months ago, Rohith noticed the onset of depression in an ASA member and took him on a long hike across the university. Murala was part of the expedition. Amidst the fruiting custard apple trees, she heard him utter words that she now wishes she could have yelled back at him across the invisible void that separated them. "Do not be alone," Rohith told the young man. "We are with you."

Those who rushed to claim Rohith in death utterly failed to notice when he got weary of life, says Riyaz Shaik, his closest friend who went to college with him in Guntur. "He slowly untethered himself from the people closest to him," says Shaik, a medical representative in Guntur. "He stopped going home to Guntur, and his mother eventually moved to Hyderabad in December 2015, hoping to meet him more often. When Rohith lost his phone a few months ago, I gave him an old Karbonn phone with an Airtel SIM. But he soon stopped using it, citing network issues on campus. I got the feeling that he was always hiding from us; he had us worried. In 2013, he had spent a night in lock-up after another altercation with the ABVP, but I learned of it much later. Similarly, his friends at HCU were blind to his past; he had not revealed much about his humble origins." This was not the chipper young man he had walked the streets of Hyderabad with until dawn after a New Year's Eve party three years ago, or the love-smitten youth who had dragged him to Tirupati to meet a girl on her birthday. "The people he spent his last months with should have seen through the facade of normalcy. Days before he died, when we spoke over the phone, he told me he was fed up of student politics, although there was a lot of work he wanted to do for his people," says Shaik.

On 17 January, Radhika and Raja Vemula waited in their rented quarters in Uppal, Hyderabad, eager to share a special meal of chicken curry and rice with Rohith. He had promised to pay them a rare visit. Instead, they heard from the university that evening and found their world instantly upended into a dimension they did not know existed. "We had no idea how he felt. He shared nothing, never talked politics at home," says Raja. "I can only remember his words of carefree wisdom when I was feeling low after a failed relationship," he adds, breaking into a tired smile. "He told me, 'If a girl leaves, don't be sad. Wear new clothes, stand at the bus stop and enjoy the view'." The profound shifts in Rohith's personality escaped his friends and family, and he was left alone, an inscrutable man on a self-destructive mission, shattered by the 'growing gap between my soul and my body'.

Madari Venkatesh. Senthil Kumar. The names of Dalit scholars at HCU who took their own lives in recent years have become unfortunate details in an issue that has rocked the university's foundations and exposed its deep- seated prejudices. But where their deaths are mourned, Rohith's is glorified as a necessary intervention in the political discourse on human rights at Indian university campuses. HCU, set up in 1974, has a history of alleged elitism that, professors say, can be traced back to the first Vice- Chancellor, Gurbaksh Singh, a chemist from Banaras Hindu University. "The first faculty appointments he made were drawn from the upper castes and with the passage of time, they gained in seniority and started running the show. It was much later that Dalit faculty members made inroads," says Captain Ravindra Kumar, chief medical officer, HCU. A dozen Dalit faculty members have resigned from their administrative positions in solidarity with the suspended students.

Bhangya Bhukya, an associate professor of History at HCU who studied here in the 90s, remembers well the turmoil when the Mandal quotas were implemented. "Even after additional seats were introduced for SCs and STs, most of them were left unfilled. To give you an example, there were only six ST students in my MA class and only three of us stayed the length of the course," he says. The experience of assimilating into a mostly upper-caste, urban classroom was 'painful' for the likes of Bhukya and Velpula. Instead of smoothening the transition, the university has been repeatedly accused of resorting to intellectual discrimination against the socially disadvantaged. Over the past decade, instances of fellowships that were cut off for no obvious reason and of years gone by without the university assigning a PhD guide to Dalit students have surfaced. Meanwhile, as more and more SCs and STs entered HCU, a new politics began to emerge on campus. They began rearticulating their histories and debunking Hindutva constructions of caste. "The face of caste has changed. Yet, there is a clear ideological gap that is the source of constant conflict," says Bhukya, who was part of the ASA in his student years.

DV Ratnakar, assistant professor of Hindi at Maulana Azad National Urdu University, Hyderabad, has seen plenty of conflict at HCU as one of the founder-members of the ASA. Dialogue and the passage of time can avert any crisis, he says, in a noisy bakery in SR Nagar. "Rohith's suicide too was avertable," he maintains. "The ASA was formed in 1993 to react to grassroots issues, to ensure a better environment for Dalits on the campus. It was never meant to be a vehicle for protesting beef bans or death penalties. If you meddle in serious matters for the sake of winning an ideological argument, you must be prepared for the consequences," he says. Twenty days before he died, Rohith paid Ratnakar a visit. "He brought along some friends. I bought them a meal and we talked about initiating dialogue with the ABVP. I warned him not to lose sight of his goal; I reminded him that this was not a bazaar, that he was here to study," Ratnakar says.

The tidal wave of support following Rohith's death is unmatched in the history of the university, but one is inclined to draw a parallel with an order of rustication issued over a decade ago. It was the year 2002 and Appa Rao, the discredited VC, was chief warden. The mess had been under student management but Rao brought in a central purchase committee, under which students would have to pay weekly for mess cards. The system in place earlier directly deducted the amount from the students' monthly fellowship fund. "We would not get the fellowship money until the end of the month, so it became difficult to pay for meals," says B Nageswara Rao, who was a PhD student at the time and an ASA member. Over a dozen students, including Nageswara Rao, rose up in protest, finally securing a meeting with Appa Rao. But the professor of Plant Sciences, unyielding in his decision, told the boys not to raise further questions. This angered them and they assaulted him in a mishap that saw police cases being filed against 10 Mala students including Nageswara Rao. The university rusticated them. "We did not lose heart," says Nageswara Rao, who is now Assistant Professor at HCU's School of Economics. "We appealed in court, which commuted the penalty to a two-year suspension. It took some of us 10 years to finish our PhD but we hung on," he says. "Failure was not an option, since we had come up the hard way." Alas, Rohith Vemula, once mad with hope, could not find inspiration in their resilience. When the university struck its brutal blow, he made no attempt to shield himself. The Hyderabad High Court would have heard the case against him and his friends in a couple of days, so what prompted him to act prematurely? Driven by a deep longing for community as well as a fierce individualism, Rohith, in his final moments, must have felt truly helpless, a star burned by his own brightness.