My Son, Not the Terrorist

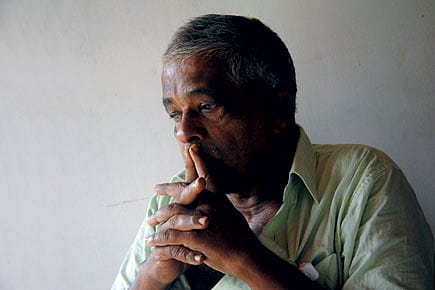

An ageing rubber farmer, Gopinath Pillai, remembers the life of his son Javed Shaikh, who was killed in a 'fake encounter' and was known as Pranesh Kumar before he fell in love with a Muslim and converted to Islam

THAMARAKKULAM, KERALA ~ The house stood alone in a grove of rubber trees. The door was open, but we could see no one inside. We rang the bell. After a while, Gopinath Pillai appeared from behind a well in the corner of the compound. He had been washing clothes—something his son usually did, he said, a hint of apology in his voice. "He was doing it today too," he added, "but didn't get time to finish."

Pillai was referring to his elder son, not his second, Pranesh Kumar, the one who made him a household name in Kerala. Pranesh, known in official records as Javed Shaikh since his 1991 conversion to Islam, was dead. He had been shot in an 'encounter' on 15 July 2004 by the Gujarat Police along with three others (including Ishrat Jahan; see 'The Innocence of Loss', Open, 19 December 2011). They had been branded Lashkar-e-Toiba terrorists out to kill Gujarat CM Narendra Modi. But it is now becoming increasingly certain that the encounter was staged. A Special Investigation Team (SIT) report released last month said as much; it led to the Gujarat High Court's ordering the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) to take over the case, which it did on 6 January, with 10 officers flying to Ahmedabad for the purpose.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Gopinath Pillai, a Nair by caste, is a believer. He is a regular visitor to a nearby Durga temple, the administration committee of which he had been president of for over a decade. That his son switched from Hinduism to Islam is something he came to terms with long ago. What he could never bring himself to accept was that his son was a 'terrorist'.

Pillai is also a rubber farmer by choice, a career turn he took after an unhappy stint in Bhopal with Bharat Heavy Electricals India Ltd (later known as Bhel) in his twenties, a stint marred by trade union trouble as he remembers it. He saw sense in returning to his native Thamarakkulam village, near Mavelikkara in Kerala's Alappuzha district, and planting rubber on his land. But since these plants take at least seven years to yield any rubber, Pillai took an interim job in Pune at an electrical goods company, leaving his wife and two sons on the farm. It was later that he called the family over, a decision prompted by concern for Pranesh. "He was in the ninth standard," recounts Pillai, "He was not very good at his lessons and often spent his days outside class. He went fishing and sometimes did not come home at night. He used to sleep on the riverside with friends. Our relatives told me not to leave the boy in Kerala. I took the entire family to Pune when Pranesh completed high school. Though I was worried about him in those days, now I know how much he had enjoyed his childhood."

In Pune, Pranesh got a job at the same company as his father, but quit along with Pillai when it was time for him to return to the rubber farm. Back home, all Pranesh would do is play cricket from dawn to dusk. "He wasted one year only on cricket" before he got a job offer from a Mumbai company whose manager was Pillai's friend. "He was reluctant," says Pillai, "but I persuaded him to go."

Within a few years, the family found Pranesh distancing himself from them. He stopped calling. He stopped visiting. Through acquaintances, Pillai learnt that Pranesh had converted to Islam and married a Muslim girl, Sajida, a girl he realised he knew as the daughter of their Pune neighbours who visited them often. With no daughter of their own, Pranesh's mother had been very fond of her. Pillai also learnt that Pranesh used to travel to Pune from Mumbai to spend weekends with Sajida's family. Afraid to disclose all this to his own family, Pranesh had found it easier to snap ties.

The son showed up only after word reached him of his mother's cancer. Turning up at her hospital bed, he told her of his marriage, conversion and one-and-a-half-year-old son (of whom he showed her a picture). "I was worried how my wife would take it," recalls Pillai, "All she said was that she wanted to meet Pranesh's wife and child. I remember how happy it made him. He hugged me and promised to bring his son and Sajida over as early as possible."

Pranesh kept his promise. In a few days, he was back with Sajida in black purdah and a baby in her arms. "My wife had to be in hospital for 20 more days," says Pillai, "Sajida stayed there throughout and did not even go home once. She dutifully nursed her day and night." Pillai still wonders why his daughter-in-law did it. "My wife had fed her several times when she was a baby. That might be the reason."

Pillai's wife died soon after. To his relief, Pranesh and Sajida kept up their visits. Religion was an irrelevant issue. "I called him Pranesh and Sajida called him Javed," shrugs Pillai, "I hardly saw any difference." Likewise, he called his grandson Appu, while Sajida called the little one Aboobakkar Sidiq. "He was quite familiar to all the neighbours. They also

called him Appu. Sajida and her parents call him Aboobakkar Sidiq. The person is the same, what is the difference?"

Pillai saw his younger son for the last time on 5 June 2004. Pranesh and Sajida, who had had two more children by then, had come in their newly bought Tata Indica to stay a few days and take Appu back after a summer vacation spent with grandpa. After they drove off, Pillai remembers getting calls from Pranesh at regular intervals along their journey. "He called me when they reached Coimbatore, then from Bangalore and then from Ahmednagar. That was the last call. I never heard from my son after that."

When Pillai tried calling, he found Pranesh's phone switched off. After three days, he got a call from Sajida, asking whether Pranesh was back in Kerala. He had dropped them at a relative's place in Mumbai, where she had to attend a function, and taken the car to a workshop to have a tyre fixed. That was the last she saw of him. "Later, I learnt from people in the workshop that four or five strangers forcibly got into the car and hijacked it. It happened near the workshop, but fear kept them from disclosing this to any investigating agency."

Pillai called every contact he had in Mumbai and Pune. Nobody had a clue of Pranesh's whereabouts. A couple of days passed. On 11 June, Pillai saw a newspaper photograph he'll never forget. It had four bodies lying lifeless in front of a familiar blue Indica. It was Pranesh's. One of the four had a shirt and pair of trousers he had only recently bought his son. This was Javed, said the report, a would-be assassin of Narendra Modi.

His head spinning, Pillai rushed to his neighbour's for another paper. It had the same picture, the same news. "I closed the door and lay on my bed the whole day. A few friends and relatives came home. I couldn't see anyone. My vision had blurred. The phone rang ceaselessly but I couldn't hear anything," he says, closing his eyes and rubbing his chest, as if to soothe the bypass surgery he'd had a few years ago.

I suggest a walk in the garden, a magnificent green. His mood changes and he starts talking about plants, showing me one with an enchanting smell, a Bhasma Tusli that he'd got from the SIT office in Ahmedabad. "I had to spend the whole day there for my interrogation. Whenever I got a break, I used to take rounds of the premises. I found these plants and took their seeds," he explains, before showing me a few more plants and gathering the nerve to return to his son's tragedy: "Where were we?"

The newspaper photograph, I say.

"I was too weak to go to Gujarat to see my son's body," says Pillai, resuming his narrative, "After a few days, I got a call from DG Vanzara, the then Deputy Commissioner of the Crime Branch in Ahmedabad [now in jail for another fake encounter]. He was angry with me for letting Sajida and her family perform Pranesh's last rites. 'You are a Hindu,' he said, 'then why did you permit them to bury his body?' I agreed that I was a Hindu and my son was born one too, but he died a Muslim and should be buried as one. Above all, I told Vanzara, nobody but Sajida had the right to decide."

On 9 August, Pillai got a notice from the subdivisional magistrate of Ahmedabad asking him to appear in court on 2 September. He took a train all alone ("Who would be ready to accompany the father of a terrorist?"). A relative helped him contact Mukul Sinha, a lawyer, who arranged for two junior lawyers to accompany him to court. The judge had a few questions in Hindi to ask. It was over by noon, after which he was taken by the police to a station and questioned. "The first question was: 'Have you brought any documents to prove that your son was not a terrorist?' I had no answer to that. How can somebody prove such a thing? We can prove somebody is a terrorist if he is; the reverse is impossible. I said nothing."

The next day, a policeman paid Pillai a secret visit. "He—a Muslim whose name I can't disclose—took me to the local mosque and showed me Pranesh's grave. He had flowers with him, and wanted me to offer them and pray for Pranesh's soul. He also offered a prayer in Urdu. Later, he told me that all four had been killed in cold blood, and that the encounter was only a drama. He took my hands in his and said: 'From here on, your son's soul will always be with you. He will give you the strength to fight this injustice.'"

Every subsequent trip to Gujarat since has proven informative. "I met good cops and bad cops during the course of this legal battle. One police officer asked me how my son had taken the 'wrong path' of conversion. I told him I did not consider it a 'wrong path'."

Pillai also contrasts the way he and Sajida were treated by the police. While he was shown respect in Kerala, his daughter-in-law was made to wait on her feet day after day at Pune's Crime Branch. "Whenever she sat on the floor with the baby on her lap, the cops would kick her," says Pillai, who also learnt that Appu had to be withdrawn from school after a Hindu extremist group threatened to bomb it for letting a 'son of a terrorist' study there.

Pillai asked Sajida to send the boy to Kerala, where he joined a school near his home. "Appu hardly knew Malayalam, but picked it up very fast. He was with me a whole academic year. We were always together, except when he was in school. We often had rides on my scooter," Pillai says, of a year he recalls as one of his happiest ever. "He was brought up to do namaaz five times a day and had fairly good knowledge of Islam, compared to other kids his age." He would drop Appu at a mosque whenever they heard the azaan (call to prayer), and wait outside. "I did not face any difficult questions over religion—either his or mine—from the people around. Members of one family owing allegiance to different religions was a normal thing for Appu. He would also come to the Durga temple with me. He was very fond of the payasam."

Sajida took Appu back to Pune once the dust kicked up by her husband's death settled down. Pillai, since, has sold the bulk of his farm to buy three flats for his grandchildren in Pune. Sajida and the three kids live in one, with rent income from the other two, though she also earns some cash giving tuitions to kids. Sajida, now remarried, retains her ties with Pillai, who looks forward to calls from (and visits by) her and Appu.

Another big relief for Pillai has been the SIT report. Though the CBI is yet to conclude its own investigation, and the encounter being found to be staged does not amount to an exoneration of those killed on terror charges, he is confident of his son's innocence. He can now die in peace, he says. "My grandchildren do not have to live as children of a terrorist. Everything I could do, I have done. I have been able to make my grandchildren's life stable and secure to the best of my ability. I am 72 and awaiting my final call from the Almighty."