My Settlement with NewsX

How I sued my former employer and won Rs 2 crore (and an SUV) in damages for sacking me

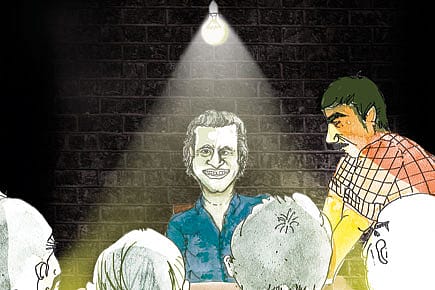

I had seen the scene many times before. In films. A dark basement room, lit by a lamp suspended over a table across which the business of interrogation is conducted. The lamp lights the tabletop and the faces of accusers who lean forward to spit out the questions. When they lean back, they retreat into shadow.

There were five people on one side of the table, their backs toward the entrance. I walked around it to take my place— alone, on the side meant for the accused.

"Tell me," I said.

Dhruva Doofus, the group human resources chief, lowered his spectacles and said: "Obhirook, we waant separation from ewe." He pushed a piece of paper toward me as he said this. "Please sign."

This was a resignation letter, which I took a little time to read—only to gather my thoughts. But it was distractingly full of grammatical errors and clericisms. I smiled inwardly at it, and my initial nervousness had gone.

"I'm sorry, but I can't sign a piece I haven't written. Never done that. But I understand your desire to part ways. Why don't I just call my lawyer, and we'll go by what my contract says?" Ajay Bhai, the group legal head, who was always dressed in these Gabbar Singh-type shirts, lost his little head almost before I'd finished the sentence.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

"He is being difficult!" he said, addressing Doofus, Nagpal The Innumerate (chief beancounter), and two extras.

Then, leaning toward me, he said: "Do you know what we can do to you if you don't sign?"

Bhai had this 'shtyle' of keeping a few buttons of his Gabbar shirt open. This was supposed to signal a threat.

"I don't really know what you can do. I know my contract says that any dispute between me and the company is to be settled through arbitration. Why don't we just honour the contract…"

Bhai had another habit. He would re-roll an already rolled sleeve when he felt threatened. "We will drag you to Bombay… for that. You don't know what you are saying. And we have evidence to file criminal cases against you! You had better seek bail!"

Bhai's tone had by now got to me. Besides, he was babbling. "Look," I said, "You can do what you please. Sort that out among yourselves. I'm not signing any resignation letter. Till such time as I hear from you in writing, I remain executive editor of the channel. Now, if you'll excuse me, I need to return to my office."

Bhai, Innumerate, Doofus and the extras were not prepared for this. I later learnt they were asked to get 30 'signatures'. Now they were struggling to get their second. The resignation letter lay where I had pushed it back: in the middle of the table, under the light. I left the room.

On the morning of 31 January 2008, reeling under stress and my annual migraine attack, I had made it to office at 8.30 to find Peter Mukerjea taking the edit meeting which I normally held at 8 am. This was odd, but Peter was, after all, Le Boss. He was the one who had brought in the investors so we could build this great, well-funded English news channel on TV, NewsX.

I joined the meeting and listened distractedly to a long discussion on the importance of being able to connect Congress politics with global warming. After a while, Peter graciously asked me to take over, and we moved to more mundane matters.

As the day wore on, I observed Doofus and (the recently elevated) Dufferdil Dutta leaning over a (single) bedspread-sized Excel sheet with what looked like names on it. Exactly what they were doing, I had no idea. But given that Dufferdil was involved, I knew it could be nothing useful.

Indrani and Peter were meeting a procession of employees; my turn would come, I suspected.

After Big Cheese Editor, I was the first employee of NewsX. This was March 2007, and there was no administration in place. So I signed a contract almost identical to Big Cheese's—bar some significant changes to the numbers, title and job description!

We operated, initially, out of a guest house in Kailash Colony in Delhi, in whose living room the few people on board used to make calls, create Excel sheets (copiously) and conduct job interviews. This was mid-2007.

Two or three times every month, there would be these 'Indrani' meetings. Indrani Mukerjea nee Bora, was Peter's wife, half of the 'Power-that-was' at NewsX, but ever keen to increase her stake.

We would unerringly know about the Indrani meetings before the mail was sent around, because a chap called Vynseley Repeater would come in advance. Repeater did not earn his name for nothing. For decades, wherever there was Pete, there was Repeat: a man who began most of his sentences with: "As Peter said…"

It was impossible to keep a straight face at the meetings. Repeater and related organisms did colourful slide shows on 'Timelines', charts they spent most of their time creating and then updating. Nagpal The Innumerate did wonderful revenue projections, using a specially leased projector. The presentations always contained graphs, which, in the first few, were gentle upward slopes—challenging treks. In a matter of months, they had transformed into near vertical faces— features seen only at the bravest heights of rock climbing.

According to Nagpal The Innumerate's numbers, NewsX was going to be so profitable in about 18 months (or something even more absurd) that everyone in the room, especially Indrani, would make millions. She would nod and smile beatifically, the way levitating sadhvis do when they like what they have seen—or foreseen. Repeater would sum up with his 'hand on his heart': "Indrani, this means we're through in two years!" On this one, I have to hand it to Repeater: he was absolutely right.

Then there were these (mainly exploratory) 'business trips' abroad. I would be on some of them, towed along by venture capital and vague suggestions that if we are to be the best, we must at least see the best.

In London, a week was spent visiting various news channel studios. These visits followed a set pattern. We would troop in, occasionally slightly late, be given a guided tour of facilities by someone of commendable patience, and perhaps watch a bulletin in progress.

We would always conclude with a look up at the crowded ceiling of a professional newsroom: the cameras, lights, rails, beams and wires that make the studio look bigger and the anchor look better. This "Eyyyyes… up!" was not a military drill, but Indrani was always the first to look up, and Repeater would follow her immediately, giving it the appearance of one.

She would then ask one of the deep questions of news broadcasting:

"What is duh height?"

"Twenty-nine feet, if I'm not wrong," our guide would say. (Or something like that—the number isn't relevant.)

"Hmmmm. (Beatific smile mentioned earlier). I tthot so…"

Months later, as our own studio in Noida was being built near a crossing named after purveyors of paan masala, I heard the question on a number of occasions. No Indrani visit was ever complete without a pensive upward gaze and a "What is duh height?" By this time, of course, the only way I could conceal my laughter was to look down.

Then there were the expats. Apparently, no startup TV station can get anywhere without FDI, or foreign direct involvement. But how/where Thakur (and Thakurain) had enlisted such a 'Hijron kaa fauj', I have absolutely no idea. There were guys who landed in India without bothering to find out whether they needed a visa. (Dubey at immigration put them on the next flight back, once Indrani sorted the business class tickets; they were then recalled, business class, after visa formalities were completed.) There were people who landed in Bombay, when they were to attend a meeting in Delhi, and checked themselves into the Oberoi. In general, the expats treated the whole thing as the Palace on Wheels of gravy trains.

The Innumerate once asked me to sort out a largish attempted fraud involving one of them and the UK-India double taxation treaty. 'Locally engaged' colleagues told me about the actual price of 'imported' camera equipment. And one 1,300-pound-a-week spot boy whom I part supervised (thank God), accused a senior Indian colleague of overcharging him approximately Rs 9 for a delivered dosa. This spot boy (this is what he did before being hired at NewsX) had taken the trouble to re-check the listed price of the dosa after insisting on reimbursing my colleague for his share of a collectively bought lunch. This was the first time he had done research on a story in the time that he had spent with us. However, he had failed to add Vat (about Rs 9) before making the allegation, and was compelled to retract when the dosa outlet gave independent confirmation.

The one man who stood above and apart from all of this was my friend Nick Pollard. Nick was head of Sky News for 10 years. Which meant dealing with Emperor Murdoch. Need I say more?

Drawing on his decades in top-flight news television, Nick would put out these incredibly lucid 'Pollard Papers' on how to go about building the channel. Sadly, Big Cheese and I were probably his only readers.

He was also a Liverpool man (rabid to a fault about his team), and favoured plain speech, once calling the inferences of an expensive survey riding on the 'Palace on Wheels' "preposterous" during its formal presentation. Trouble was, there was just one Nick.

Back up in my room, I made some calls. Big Cheese said, "You've read your contract, just stick to it." I spoke to Kailash, who was clearing his locker, supervised, and told him what had just happened to me. He wouldn't stop crying.

Meanwhile, the penny had dropped in the basement. Bhai and gang made their way hurriedly up to where I sat. Bhai accosted me as I was telling Repeater the story of the last half hour.

He addressed Repeater, rather than me: "No further engagement with this man! Take all identity papers and any company property that is with him. Right now! The car. Take the car, that is company property. Remove him from the premises and put up a notice saying he is not to be allowed in, ever!" Man, Bhai was on a roll.

A crucial member of Bhai's gang wasn't among the basement lot and now scrambled to join the action. Pradeep Proto-bhai was an assistant of Ajai Bhai, but sported a different look. A stocky man with a crewcut, he had had a cordless mobile phone earpiece surgically attached to his left earlobe. This ornament caused him to give the impression that he was a borderline case who constantly talked to himself. If you conversed with him face-to-face, this notion wasn't entirely dispelled. He had earned a law degree somewhere, but generally made it clear that his core strengths were mainly in the realm of embedded telecom and the quasi legal.

Led by Proto-bhai, a grinning pack of hyenas (and some confused security guards who had just that morning maaroed the customary salaam) now invaded my cabin to reclaim 'company property' and get me to leave.

This was happening in the main newsroom, and the polite-to-a-fault Rajesh Sundaram was around. Rajesh and I had worked together for a very short time, but long enough to figure out two things: that he worked insanely hard, and that there was this other, very different, volatile Rajesh about whom I had only heard.

Rajesh barged into my room, pushing through the pack tugging at my laptop and clothes. A free-for-all was about to ensue. I called for peace. Said all property would be returned, and that I would leave the moment I was given a sack letter. Till then, I was not budging.

Protobhai, defeated, eventually went and got one printed and signed it himself. He probably consulted Bhai and Repeater, but 'thinking things through' wasn't a strong suit with any of these fellows. The letter said nothing about why I'd been fired. Just that I had.

My colleague Narendra Nag was off that day, but he lived close by, and someone had called him about the mess in the newsroom. He arrived in no time, and threw his laptop on Repeater's sofa. "Here. I believe we are being sacked…" he said, giggling. Repeater, who was in the process of chopping up my company credit card said, "Why just believe? You are being sacked." He was laughing.

I went down to the studio floor just afterwards to say goodbye to my friends. Repeater and gang followed, arranging themselves in a phalanx behind me. Some colleagues wept, others were stunned. They hadn't seen anything of the kind before.

Doofus was among those in the phalanx. His goodbye was: "Obhirook. Please, hain, don't mind. Naathing paarsonal." (The next day, he summoned an employee in his department to ask why she had wept the previous evening. I thought he got a brilliant response: "Sir, I will cry even when you leave also. When are you leaving?")

Rajesh, Nag and I left the building. The two of them without even the comfort of a sack letter to cling on to.

I did not know that trouble had started until well after it did. The First Information Report in my head has Indrani pacing up and down the newsroom, calling someone (a middle-level Delhi Policeman), and telling him, through gritted teeth, that the retribution she has in mind will "Make dem regret duh day dey were born". This was 10 January, about a fortnight before Big Cheese left.

I soon learnt that this had to do with a 'media' blogger called 'K', well known for slander. This fellow had put out stories and encouraged comments, all anonymous of course, saying things that had caused our madam grievous harm. The posts had less to do with NewsX than with the troubles at the INX Group's flagship company 9X.

Something that 'anonymous' said on 9 January had particularly angered Indrani. A Pakistani drag artist who was given a show on 9X purely because fully made up he closely resembled Indrani, was now going to be dropped, anonymous had gathered.

I have no time for anonymous bloggers. I think they are the same people who send anonymous letters.

I spoke to Indrani briefly after she was done with her phone call. Peter was hovering somewhere closeby. I told them what I knew from experience: that you will sometimes get slandered on the internet by people who you don't know/don't care about. That is the nature of the beast. The worst thing to do is to react, by, say, posting some kind of rebuttal or launching an investigation that the blogger might find out about. In a perverse way, this is only treated as one thing in a medium where content is king: more content.

What I did not tell them in any detail is the fact that I had been personally attacked by this 'K' on several occasions. And that I knew him. Fairly well, actually.

Several years ago, a friend/colleague mailed me a post about yours truly on K's blog. Regular journalists like me look for a byline, some form of attribution, or at least a suggestion that someone is taking responsibility for the words posted. There was none.

These were words that just floated around cyberspace and didn't seem to have a mothership. I cannot say I wasn't upset. But I was also curious. I read the whole blog over, and within a few minutes, I had some answers.

Of course I knew this 'K'. He had worked with us at Hindustan Times. In the business section, as a trainee reporter. He would bring me copy that he hoped would make the front page. It did, occasionally, after a rewrite and one recurring spelling correction. K didn't know how to spell the word 'definitely'.

"Kushan," I would say, "when will you give me some copy that doesn't have a 'definately' in it?"

On reading his blog, I figured that my attempts to improve his general level of literacy had definately not worked. Definately was all over the place, like fingerprints.

I have not met Kushan Mitra in many years, but I'm told he still fits, just about, under hominids; a Homo pompous perspiris. I remember him as a somewhat frustrated beta specimen with a thyroid problem. I also remember he had a capacity for gossip (intake/output) that would shame weathered Mah Jong masters (or is that mistresses?). But most of all, he had a misplaced sense of entitlement, and, by extension, immunity. This came from the fact that his dad was a prominent journalist and later Member of Parliament.

Chandan Mitra is also someone I know. He is an acquaintance, rather than a friend, but I have invariably enjoyed his company whenever we have met. I have no political views, so his publicly held ones don't matter to me. In fact, I have often been entertained listening to him defend them in hostile conditions. This he does with humour and scholarship.

On occasion, when I was at HT, Chandan had even praised my work to friends and colleagues. The few times we spoke, he never once mentioned his son. Kushan, on the other hand, could slip information about his lineage into a conversation about water polo, and usually did.

When I thought I had Sherlocked K's identity, I went excitedly to my colleague and told him I had it figured. He looked at me with surprise and disgust: "The guy boasts about it wherever he goes. You didn't know?" Everybody knew.

The smartest thing I did, though, was not post an angry rejoinder on his site. Neither did I make any effort to stop him. I turned away. For who would I sue or pursue? Google? And was it worth it? I advised Indrani to do the same.

At about 5.00 am the next morning, I got a text message from Indrani. It said that she couldn't sleep—because somebody pretending to be a friend had 'betrayed' her, and that she knew who it was. I wondered why such a message should come to me. And why at that hour.

I happened to be awake. Work started at 8 am in those days, and in Noida, an hour-and-a-half's drive from where I live. I replied saying she should get some sleep. She messaged back instantly. (These text messages were part of this writer's legal notice to the channel). A rambling, threatening text on a trident of themes: friendship, betrayal and revenge. This was odd, I thought.

At office that morning, I mentioned the message to Repeater. He told me he had received an identical message. When Big Cheese came in, I showed him the text—and he showed me his phone. Same message. Finally, Repeater told me, Peter had got it too! (Repeater did tell the truth on the odd occasion; I checked with Peter.)

So, what was this about now? I was, as I understood it, part of a quartet of suspects, all of whom the accuser knew well, including one who was her husband. One of us was supposedly posting slanderous material on young Mr Mitra's blog.

The whole gig was becoming surreal.

It went downhill very quickly after this. The Mukerjeas began giving interviews/ planting stories in the press about Big Cheese 'parting ways' with NewsX. The place was in ferment. On 14 January, a strange set of 'news clips' arrived in the inboxes of senior managers. This was sent out by someone in CMCG India, a company hired by the Mukerjeas to take care of public relations and strategic communication for the group. Their main task, it seemed to me, was to mail these fairly harmless daily roundups of items that everyone had probably read anyway, for internal consumption.

But that morning's clips were different:

'Final match for IPL media rights today', The Economic Times, 14 January

'Big Cheese Editor falls out with INX?', DNA, 14 January

'Yash Raj Films to launch new TV channel', The Asian Age, 13 January

These headlines were followed by a few links to media websites that also had versions of story number 2. Nick, a little baffled, asked me why a company that was trying to stop the spread of "rumours" would circulate them internally. I said I didn't know.

A flurry of emails flew back and forth. A concerned investor asked Peter to sort the matter out 'INTERNALLY!' (in an otherwise all lower-case email). He also asked the Mukerjeas to consider issuing a joint statement with Big Cheese that would stop all the speculation. Peter's reply: 'Relax.'

In about a week's time, around the third week of January 2008, Big Cheese had made up his mind to leave. He arrived at an amicable settlement. On 29 January, INX issued a 'parting ways' press release.

A day later, the entire staff was summoned for a meeting: a formal announcement by Peter on changes and the way forward. Peter began by saying that Big Cheese remained a friend, but then, shifted from clipped English to the heartland trader's lingo. The parting came, he said, because "Bijness ij bijness".

The play took a bizarre turn right after this. Indrani grabbed the mike from Peter before he could finish, and gave us a masterly lesson in man management.

"I just wanted to say dis. Over duh last few monts, I have received many anonymous e-mails from people letting me know how things were being mismanaged in dis place. Now we have taken action. I want to thank all dose brave people, who kept me informed. Many of dem anonymously, because dey were afraid of consequences… Let us give deeze bravehearts a big hand!"

I was standing in the first row, facing Indrani, and bit my hand to prevent a laughilepsy attack. Those in the bemused gathering whom she was making eye-contact with obliged her with tentative patter.

Within 36 hours of this, on 31 January, I was sitting in front of Peter and Indrani in Big Cheese's former office. They asked me what my plans were. Was I going to leave them in the cold? What if Big Cheese made me an offer in the near future?

I don't really know what they were thinking, or what kind of idiot they thought they were talking to. Just that morning, they had held a series of meetings (without my participation) where they clearly said that I was out, as was anyone seen as loyal to Big Cheese/me. Those in the meetings had let me know the moment they came out. The long Excel sheet that was being prepared in the conference room adjacent my office by Doofus and Dufferdil had the names.

I took the day to read my contract carefully for the first time.

In between, Repeater had made covert contact. He dragged me down to the basement: "Avi… Big Cheese is out. You need to step up to the plate, Avi. We all know you can run this thing. Just let them know you want to… Hand on my heart, leave the rest to me."

My meeting with the Mukerjeas ended with my saying I left the next steps to them. And that my loyalty to the channel was fairly obvious from the way I had helped build the team and hold it together through a fortnight of turmoil. ("Will we launch at all? Should we look for jobs?")

Peter said he would need 24 hours to "digest that". After which we would talk again. Then they were off.

At about five, I received a call from The Innumerate asking if I was free to meet him at 7 that evening: "Some pending budget issues…"

I was to interview someone at 7pm, so I asked him if we could do it right then. His cabin was just two doors from mine. He said "No, no, no, friend!" Okay, I said, let's say 6 in the evening then. He readily agreed. "Friend, I will call you."

At just past 6 pm, I got an unexpected, distraught visitor. Kailash Menon, a promising young man we had hired for our auto show. He was weeping.

"Why have they done this to me?" Kailash sobbed, waving a letter at me.

I said: "Calm down man. Who's done what to you?"

"They made me sign a resignation letter. You had said my work was good…"

"Who made you sign…?"

The phone rang. It was Innumerate. "Avirook, can you come to the basement for our meeting?"

I told Kailash to wait till I was back.

Chhuttan Yadav has been our driver for several years now. At times, he is infuriating: getting fined, getting lost, getting in the 'cash' lane when we have a drive-through tag. But my fondness for him matches his intense loyalty to our family.

So when some of Proto-bhai's underlings (micro-bhais) went down to the parking lot and demanded the keys of the new SUV the company had given me, he told them to buzz off. He had tried to call me, but there were too many micro-bhais, apparently.

Poor Chhuttan, who had no idea what was going on three floors above, had the keys snatched away from him—and received a couple across the face for his brief resistance. He told me later that the blows didn't matter.

He was more worried about the car—a blue Ford Endeavour, which he loved dearly—and how he would explain a car-jacking from the office parking lot.

I cared about the blows, though. It just wasn't fair.

On the morning after, I sat on our terrace wondering what to do. My sister-in-law Anjolie, a lawyer (though her thing is disputes between countries), put me in touch with Rajshekhar Rao, whom she knew from law school.

Raj heard me out and said the first step was to send a legal notice. The 'non-speaking' sack letter and my contract made for a reasonable case.

Meanwhile, friends had fixed a meeting with the then Information & Broadcasting Minister PR Dasmunshi. NewsX was preparing to go on air, so it had regular dealings with the Ministry. The minister was shocked when he heard about events of the previous night, and he seemed to know a lot more about some aspects of NewsX than we did.

That evening, Indrani, who claimed she only "heard" about the newsroom fracas, wrote me an apology on email. I spoke to Raj the moment I got the mail, thinking it was an admission of wrongdoing. He just said: "They are being advised well."

But events were moving fast on 1 February. No sooner had I got the mail from Indrani, than there was a statement of condemnation from the I&B minister, chastising the promoters of NewsX, on the wires. The mainstream media, which had followed Big Cheese's last days at the channel quite keenly, had a new story.

The man handling the press at INX Media, NewsX's mother company, was a chap called Pavan Chamcha, whose principal job was to plant pictures of Indrani in the media and ensure she was described as the company's founder. He was foolish enough to engage 'K', posting stories that suggested a conspiracy against the Mukerjeas. One of these stories concerned a former colleague of Peter who was also launching a new entertainment channel.

Chamcha called this respected TV pro a "sandwich seller", publishing his illiterate rants in the blogosphere from a cyber cafe close to the 9X office in Bombay. Then, he would come back and send out gloating emails to senior management that provided hyperlinks to his work.

The management realised what a mess a mail-trail might cause were it to fall in the wrong hands, and had it wiped out. But this was done a few forwards-to-Gmail too late. Chamcha's work was of irresistible daftness, and just begged to be passed around.

Under formal orders, Chamcha went to work on my reputation, putting out a press statement late in the evening saying that speculation about Mr Sen's sacking needed to end. He was fired because he was using the company laptop to view pornography.

This was a full day after a sacking letter that said nothing, an apology, and more than 24 hours in possession of a laptop which should have been sealed as evidence the moment I handed it over. The oddest thing was, I received another apology, this time from Peter, after Chamcha put out his statement. What were they thinking?

Nevertheless, I was hit really hard. The next day's papers carried the statement—without a comment from me. At home, I could explain, but would the other soccer dads I'd meet at my son's school have read…?

I spoke to Raj. "They've gone mad," he said. "This is great."

My suddenly-former colleagues kept in regular touch. The office had been turned into a fortress, they said. Security guards paced up and down the newsroom, cameras and microphones were installed everywhere. The editing bays had been shut off, as they were now being used to review CCTV footage of the day of my firing. In the hope that something incriminating, like a puff in a non-smoking area, might turn up? Full blown paranoia had taken over NewsX.

It was time for my legal notice to go out. Raj said he would seek senior lawyer Siddarth Luthra's advice, at least partly because Siddharth was well versed in media matters.

Siddharth was short and sharp when we met at his Defence Colony office in early February 2008. He said he'd advise Raj on the case.

He then turned to Rajesh, who just happened to have come along (we were all jobless), and said: "What can I do for you Mr Sundaram?"

Rajesh said, softly: "Nothing. I… just got a letter from them saying that they had accepted my resignation."

"But you didn't resign!"

"No…"

Siddharth turned away and called a clerk in. He was done with us. He then began dictating a legal notice on Rajesh's behalf. It said that it was clear from the acceptance letter NewsX had sent Rajesh that they had forged his resignation letter. (Rajesh hadn't written one.) It advised them to return the forgery. Should they fail to do this, and try to destroy or deface the forgery, they would be committing a number of serious crimes.

When Ajai Bhai received this notice a few days later, he sent Raj a one word message: 'Googly'.

He then went into overdrive to settle Rajesh's matter. (It was eventually settled, though it took its time.)

A month had passed since I'd demanded damages—stubbornly insisting that the car be included as part of any settlement, much to Raj's amusement. Nothing much had happened apart from counter notices, copies of which were deliberately sent to my parents' home in Calcutta.

Bhai and Raj met a couple of times, and exchanged telephone calls. Bhai was desperate to clean up the mess that he had created. So there was a series of absurd offers that he conveyed at various stages. 'We'll give him three months' pay'. 'Okay 6, and that's final'. 'Look, this is more than we've ever given anyone, but as a special case, we'll pay him a year's salary'. And the best one of them all: 'We'll pay him for as long as it takes for him to find another job'!

Raj would come back to me with these offers knowing full well what I was going to say. Eventually, Bhai got frustrated and asked him: "What does this guy want, a year's pay is a lot of money. Doesn't he need it?" Raj didn't answer the question directly. He told Bhai: "We're dealing with a Bangali who just requires cigarettes and occasionally fish curry. That, he's managing…" (I told Raj this was incorrect. My thing is pork, not fish.)

I met Big Cheese. He said: "Just hang in there. They will have to pay you…"

In his expert dealings, Raj communicated two things to Bhai: that we were serious about taking this as far as we could; and that while they had a large business to run, we had only one agenda—which was to make them pay. Bhai could expect more googlies.

So Raj slipped in the doosra. He told Bhai about Chamcha's 'sandwich-seller' email, for instance, and I think Bhai was vigorously re-rolling his sleeves for the next half hour.

The promises to resolve the matter became a little more sincere after this, but he said the amount in question needed board clearance.

Early one morning in March, when Raj and I were just about done waiting, and ready to take matters to the next level, he found an email sent by Bhai the previous night. It said INX was willing to pay Rs 2 crore. Cash flow problems, however, would mean that the money would come in four equal monthly instalments.

I don't know if there was a connection, but Bhai developed a large blood clot fairly soon after he hit 'send' and had to be hospitalised. By 15 June, he had recovered enough to sit across a table from me once again. Nagpal The Innumerate was there as well, so was Proto-bhai, and a couple of micro-bhais.

We were at the guest house where we'd begun. "Friend, please sign this," said Innumerate, politely. It was a receipt for the first tranche, a cheque which I inspected for grammatical errors. It was signed 'I Bora', Indrani's maiden name.

I asked about the car. One of the micro-bhais said it was downstairs, and had just been serviced, "insurance, pollution complete" and held out the key. I wouldn't take it.

He was a little puzzled by this. As we walked down, I smiled and told him: "Give it to the man who you took it from." Chhuttan Yadav was waiting next to the car, beaming.

By 15 September, my business with NewsX was settled, the last cheque handed over. It was time to go off 'Looking For America'. I left a week later, spending time doing some research. While reading about the civil rights movement, I found this quote:

'The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards justice'—Martin Luther King Jr.

The channel's slide that began with Big Cheese's departure continued after mine. Almost every member of the senior editorial team left within a matter of weeks, as did a whole bunch of talented youngsters. We would call ourselves 'XNews'. No serious journalists would join, and the channel floundered. In January 2009, while travelling in the US, I heard it had been sold. I wish to clarify that I have cordial relations with the new management, which has begun turning things around, and I wish the channel the very best