A Ride Down H1N1

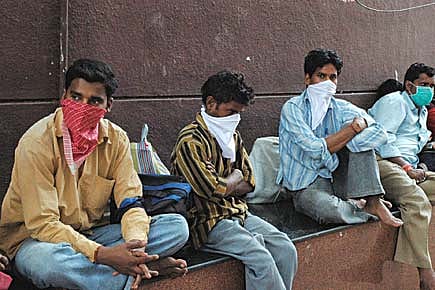

With the fear of swine flu spreading faster than the virus, Pune has become a city of masked people with strange encounters.

My homeopathy doctor friend Atul Modi walks past me, his face covered like a Chambal dacoit, at a normally buzzing but now desolate bookstore in downtown Pune. I decide to confront him. "What's up doc? Do you think the virus is going to creep into your nostrils from the air?"

Dr Modi, not a man for jokes in normal times, narrows his eyes (and while I couldn't see it, I felt his lips pursing) at my mocking tone. He declares gravely, "To begin with, the Influenza A (H1N1) virus was being transmitted via physical contact. Not anymore. It is hanging in the Pune air. That is why there is need to cover your face." He's not finished. "The worst is yet to come. The winter months will spread the disease further." With this prognosis ringing in my head, I take quick leave of the good doctor.

I then approach more masked strangers, the store's sales staff, to help me in my hunt for audio CDs of MS Subbalakshmi and Jagjit Singh, and DVDs of Little Zizou and Mee Shivaji Raje Bhosale Boltoy. With Pune beginning to seem more and more like an abandoned city, these will hopefully help me enjoy my own moments of solitude over the weekend. I reach the cash counter, and what do I see there—a face, in its entirety. It's Meera, the manager, punching away on her calculator, her worry lines telling an entirely different story. "The mall was shut for three days. I hope business picks up over the weekend," she says.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

Outside, the streets are empty, and not just because it's Independence Day. If you ride a mobike in Pune, like I do, you'll know this is a rare moment that should be enjoyed to the fullest. After all, Pune has an estimated 1.3 million two-wheelers, the highest in the country, and nearly 0.30 million four-wheelers choking its streets. Given this, it felt like being transported to Pune of the 1960s. The only difference being that the few Puneites to be seen on the streets are walking around in masks as if they expect to be attacked by aliens at any moment.

"Wearing masks is becoming some kind of a fashion statement now," groans Dr Anju Kagal, microbiologist at Sassoon Hospital. Quoting the guidelines of the Centre for Disease Control (CDC), Atlanta, US, about protective masks, she points out that it is actually doctors and elderly care-givers treating H1N1 patients who need to wear a three-layered mask, snugly fitting their faces. "It does not make any sense for people to wear handkerchiefs and masks on the roads of Pune," she adds.

The situation, though, was much worse a fortnight ago, the day after 14-year-old schoolgirl Reeda Shaikh succumbed to the H1N1 virus. The average Puneite panicked. Nearly choking behind the tightly-bound pieces of cloth on their faces, people with even a remote hint of cough and cold hastily joined a serpentine queue outside the Naidu Hospital for Infectious Diseases to submit throat swabs for testing.

The scare spread faster than the virus as three more H1N1 deaths got reported—a young ayurveda practitioner from the Tingrenagar area, a housewife from the middle class locality of Kothrud and another schoolgirl, this time a 13-year-old from the Peth areas of old Pune. The civic administration responded by setting up 15 outpatient department H1N1 centres, and publicised it through local newspapers, complete with the mobile phone numbers of the doctors in charge. As can be imagined, the phones of the hapless doctors never stopped ringing.

Queries to several doctors in the city ranged from the general to the absurd. A section of the local press reported how doctors in the upmarket Kalyani Nagar and Koregaon Park areas got calls from people who wanted to know if they could get immunity from the disease if they attended 'swine flu parties' reportedly being hosted at 'hefty' prices by some patients who'd recovered from swine flu.

In the meantime, local corporators demanded that the civic administration shut down the entire city, a la Mexico City. However, Pune district collector Chandrakant Dalvi ordered just a three-day closure of malls and multiplexes and a ten-day closure of schools and colleges.

Of course, it didn't take much from the administration to keep most people off public spaces. Vinay Shetty, owner of Bamboo House, a popular 500-seater, multi-cuisine restaurant, said he'd recorded a 70 per cent drop in sales over the last one week. "Not only have we lost sales, but our staff from places like Uttar Pradesh and West Bengal have also all gone home," he said.

As for the Ganesh festival, for a change, the over 200 prominent Ganesh mandals in the city have decided to keep the festivities low key. Besides, Pune MP Suresh Kalmadi has postponed till December the Pune Festival, a week-long cultural and sports extravaganza coinciding with the Ganesh festival.

However, it is not as if Pune has buckled completely under the H1N1 scare. Some of the survivors paint a very positive picture. On ringing the Deshpande residence to speak to 13-year-old Sanyuktaa, one of the 20 students who'd tested positive for the H1N1 virus, she says rather chirpily, "I was a bit scared the first day I was admitted to the quarantine ward at Naidu Hospital. However, the doctors and nurses put us at ease. The five-day stay at the hospital was like a mini picnic, as all the children in my ward happened to be from my school. We watched films, read books, narrated stories to each other and generally had a good time." For the record, Sanyuktaa was quarantined at home for a week after her return from the hospital, and her holiday from school is about to end soon.