Scrappy Stuff as Strategy

OF ALL THE bequests of social media, the utterly extraordinary influence of imagery appears the most obvious; the speed at which images are transformed, less so. Perceptions of popular politicians are particularly volatile; those of faceless folk slapped with group labels, far less so: a WhatsApp video clip of an anonymous 'Kashmiri girl' that went viral last fortnight, with a young woman clad in nothing but a clingy kurta all asquirm and agurgle on a random rooftop in the sheer abandon of a winter drizzle, for instance, seems to have startled rather than spurred WhatsAppers to think of individuals as individuals (as liberals would). Alas, what people make of ideas tends to change at a pace much too sclerotic for any good; how the rabble responds to slogans that appeal to hoary old beliefs, no less so.

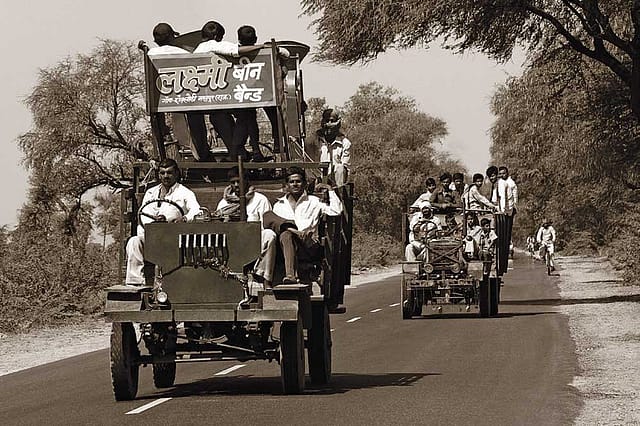

Leave aside ideologies of leftist and rightist extremes, perhaps the most remarkable recast story of the past decade is that of an Indian concept called jugaad. Scorn-worthy till not so long ago, it has almost acquired the status of a business buzzword now.

Early familiarity counts, and my first impression of jugaad as a wiseguy workaround was formed back in boarding school as a reckless teenager. For coffee at midnight, a cricket cup taken off our hostel's trophy wall would act as a vessel, and a Sandoz eraser pinned at both ends by a divider—taken out of a geometry box, snapped apart and wired to an electric socket— would be used as a make-do water heater. It was a survival aid, as we saw it, but the thought of jugaad being offered as advice for CEOs, no less, would've made us splutter over our brew.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

Yet, it's not a word thrown around just in jest today, it's an actual subject for analysis at Cambridge University's Judge Business School, among others. A big role in its ascent to academia has been played by the 2012 book Jugaad Innovation by Jaideep Prabhu, Navi Radjou and Simone Ahuja, who portray it as a form of ingenuity that's both flexible and frugal, best deployed against adversity. This is something that clever companies don't merely resort to, they argue, but also apply as a strategy.

Well, well. Could 'jugaad innovation' set the world of business abuzz the way that Japan's kaizen perfectionism did in the 1980s? Don't bet on it. Critics see little in jugaad beyond an exotic name for scrimpy operations. Others accuse the authors of conceptual overstretch for citing examples of CEOs flying by the seat of their pants, so to speak, even though that's what dynamic entrepreneurs say they do anyway: reshape their strategy on the basis of live market inputs as they go along. What few dispute, however, is that it's a snappy word for a scrappy way to solve a problem. Why, it has even found itself in Oxford Dictionaries, an inclusion for which credit was swiftly claimed by a Hindi flick that had a song-and- farce sequence in the concept's honour, a movie best recalled only for its quip, Yeh duniya ummeed pe nahin, jugaad pe qaiyyum hai' (The world survives not on hope, but on a quick fix).

For all its new respectability, it has long been the stuff of winks and nudges. Attribute this to the broad sweep of its use as a term in India, covering everything from chewing gum acting as an adhesive to high-level bribery bending a rule or two. While urgency is usually what calls such an approach into play, it often draws upon the sort of ethical ambiguity that goes with an 'anything-goes' attitude. This throws up an ends-and-means perplexity that champions of jugaad have left largely unaddressed. Indians are famous for working in the grey zone between moral relativism—where it's okay to be economical with the truth, say, or give safety norms the go-by—and categorical imperatives that specify distinct no-nos in rejection of the notion that noble ends could justify ignoble means. On this spectrum, recent years have seen a spectral shift for the former in this country.

If sticklers for propriety react with dismay, it's for the same reason that nobody should wire up an eraser for a caffeine shot: safety may not make for a heroic self-image, but the risk of lives lost far outweighs the gains of slapdash action against a 'crisis', and it's hard to believe that similar trade-offs don't operate on higher-order forms of jugaad, whatever the aim.

All in all, while the West's academia has done well to welcome this desi concept, any such scramble for a fix needs the restraint of calculated clarity on what risk is worth how much. No one would want a jugaadu job at a nuclear facility, for example, even if the stakes are sky high. At least one no-no does exist that ought to find a global consensus.