The Legend of the Poonawallas

VACCINE KING CYRUS POONAWALLA, who made his fortune in the second half of the twentieth century, best exemplifies the continued success of Parsi entrepreneurship. Cyrus is today the richest Parsi in India. His company, the Serum Institute of India (SII), is the largest producer of vaccines in the world in terms of dosages and has been in the global spotlight because of the coronavirus pandemic. Cyrus is the chairman and managing director of the privately owned company and his son Adar is the CEO. Politico magazine described Adar last year as ‘Perhaps the most important figure in the global vaccine race who isn’t working in a laboratory.’ Because of SII’s reputation for selling quality vaccines at relatively low prices and its huge production capacity, international vaccine developers lined up for a possible collaboration with the group from early last year, as the coronavirus spread rapidly around the world. SII had to choose from nearly a hundred vaccine candidates, settling for five, most notably the vaccine developed by the British Swedish company AstraZeneca and Oxford University which was rolled out in India in January, this year, as Covishield. Adar struck a deal to produce a billion doses of the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine for developing countries, including India.

The world anxiously watched the Covishield trials, since it hoped the vaccine could prove to be the silver bullet to deal with the pandemic. It was not just one of the first vaccines to be granted approval, but unlike vaccines in the West produced by pharmaceutical giants, Moderna and Pfizer, Covishield is relatively inexpensive and, importantly for developing countries, it can be stored at a much higher temperature of minus two to minus eight degrees Celsius as against the extreme minus seventy to minus ninety degrees Celsius cold chains required by some of the other vaccines. Unfortunately, the hoped-for storyline of SII being purveyor of COVID vaccines to the world did not unfold quite as hoped for. Rare instances of blood-clotting related to AstraZeneca vaccinations dented confidence in some parts of the world, and other vaccines appeared to show a higher efficacy record. From a business point of view, the Poonawallas took a big hit, with the government taking over the distribution of the vaccine within India and prioritising the country’s needs because of a surge in COVID cases. By March this year, the government had temporarily banned export of vaccines, and SII, which had already delivered 60 million doses abroad, could not meet its remaining overseas commitments for the time being. SII, which produced around 90 per cent of the COVID-19 vaccines in the country in April, had at that stage a monthly production capacity of 60 to 70 million doses. With the government purchasing the vaccine at a highly subsidised rate of around US$2 per dose, about one tenth of the average price globally, Adar’s plans for further expansion of his facility were on hold. It was only in April this year that the government advanced Rs 3000 crore to the company for purchases.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Adar took a major gamble by beginning the manufacturing process for the AstraZeneca vaccine in October, long before he got the go ahead for the licence from the Indian health regulatory authorities. He also drastically expanded his manufacturing facilities so that they could increase productivity. ‘I risk losing $200 million if it doesn’t work,’ Adar said in an interview. He added that, ‘Some people called me crazy, but if we didn’t commit to the trials, we would have lost six months.’ Apart from their own investment, the Poonawallas had to raise an additional $600 million, some of which came from the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and some from private equity networks. SII was meant to provide the vaccine to some ninety-two countries, including much of Africa, and several of the world’s poorest countries that are part of the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunisations (GAVI). By the end of December 2020, SII had stockpiled 200 million doses of the Oxford vaccine.

The coronavirus crisis, no doubt, presented a huge opportunity for SII but the scrutiny and pressure on the company have been enormous. Adar admits that 2020-21 were stressful years, where every week a new challenge popped up. While the SII bet heavily on the Oxford AstraZeneca vaccine, it also entered into a few other collaborations and has at least three more vaccines in the pipeline. The Novavax vaccine, which is effective against new virus mutants, is expected around September. SII’s handicap is a US ban on exporting raw materials for its manufacture, which had held up stockpiling. The company hopes to produce the single-dose nasal Codagenix vaccine in 2022.

While Covid-19 and the general economic downturn in India have had a negative impact on some major Parsi fortunes, a graph of the Poonawalla wealth would show a steep rise. In October 2020, Bloomberg listed Cyrus as the fifth wealthiest Indian businessman with an estimated net worth of US$13.9 billion. According to the Shanghai-based Hurun Research Institute, Cyrus Poonawalla’s wealth grew by 25 per cent in just the first four months of the pandemic, his net worth rising faster than any other Indian billionaire and fifth fastest in the world.

Cyrus Poonawalla, the septuagenarian chairperson of the SII achieved billionaire status fairly recently. He was not born to great wealth. His great-great-grandfather, Dhanjishaw Ankleshwaria, was a leading contractor. He was known respectfully as ‘Poonawalla seth’, which is why some branches of the family took on the surname ‘Poonawalla’. Dhanjishaw had eleven sons and three daughters, so each offspring effectively inherited ‘only’ some eight properties. The fact that Dhanjishaw’s descendants were not as wealthy as they might have been because of the large size of his clan seems to have had an impact on Cyrus who consciously decided to keep his family small. He was once quoted as saying, only half jokingly, ‘I cannot afford more sons.’ He concedes he said that because had he had more than one, ‘I would see a fight. Which has happened in most families.’

Cyrus’s grandfather, Burjor, lost much of his share of the family fortune, except for the stud farms and a real-estate business; Cyrus’s grandmother used to bemoan the fact that her good-hearted husband had turned his gold into dust. After graduating with a degree in commerce in 1962, Cyrus saw that there was little future in running the businesses he had inherited from his father, Soli. Stud-farming was not a going proposition after the then Bombay state chief minister, Morarji Desai, an ascetic killjoy, had banned horse racing. Things have come full circle, complains Cyrus, now that the government’s high GST rates, as a result of categorising horse racing as gambling rather than as a sport, have once again made it difficult to make a profit from breeding horses.

Instead of racehorses, Cyrus considered producing race cars. Though he put together the prototype of a Jaguar-type luxury sports car, he realised it was not going to be commercially viable in India back then and dropped the idea. It was a vet, Dr Balakrishnan, who gave him the idea that would transform his fortunes. Balakrishnan pointed out that the Poonawallas had been donating their horses, after breeding, to Mumbai’s government-run Haffkine Institute where they were used in the production of antiserum for the tetanus vaccine. He suggested that Cyrus put up a processing plant in a corner of the Poonawalla farm and get into the business himself. The family’s advantage over the big pharma companies was that they had plenty of land to house the horses. Cyrus and his brother Zavere soon realised they were on to a good thing. The family doctor, Jal Mehta, who subsequently became vice-chairperson of SII, introduced Cyrus to Dr P.M. Wagle, who had just retired as director of the Haffkine Institute. Cyrus employed two scientists to build a small laboratory in a corner of the farm, which had a lot of barren land for breeding.

In 1966, on Cyrus’s wedding day, the foundation stone for the SII was laid. It was a small-scale industry, with a capital of five lakh rupees. The company’s rather grand name, Cyrus admits, was a bit of an exaggeration of both the scale and standing of the business at the time. But the name has proved so lucky that no one is in a hurry to change it. In 1967, SII began making serum for the tetanus antitoxin, of which there was a huge shortage in the country. Cyrus, who has always loved horses, stopped using them to produce the serum, moving on to discarded army mules instead. The company quickly became hugely profitable and branched out into the manufacture of other vaccines. Today, SII specialises in the DPT, MMR and Pentavalent vaccines and has expanded to produce pneumococcal and rotavirus vaccines as well. The SII would have grown even faster had the brothers looked for partners or opted for a public listing. But Cyrus did not want to lose his independence and control; in fact, he always had concerns about retaining control. So much so that even when his brother Zavere wanted to bring his son into SII, Cyrus demurred: ‘I feared that at some stage it could lead to a rift with my only son.’ Zavere decided to exit the company, a decision he probably now regrets. Cyrus, who was the majority shareholder and CEO of SII, says he advised his brother against selling out.

THE COMPANY’S BIG BREAK CAME WHEN IT got WHO accreditation to produce vaccines. UNICEF is now one of the SII’s biggest customers. Another major client is the Pan American Health Organisation, which honoured Cyrus in 2010 for his contribution to eliminating rubella in the region. The Gates Foundation has often pumped cash into the SII and has credited the company with helping to eliminate meningitis in hard-hit parts of Africa. The SII has manufactured nearly 1.5 billion doses of vaccines for use in around 170 countries in the developing world. Cyrus has transformed the global industry by offering large volumes of serums and vaccines at half, and sometimes even one-tenth, the cost of such vaccines elsewhere. Understandably, big pharma in the United States and Europe is anxious that SII be kept out of their markets, which they guard zealously through byzantine patents and intellectual property laws. Despite hurdles placed in its way in Europe, America and China, SII has conquered much of the rest of the world. Cyrus is confident that the firm now has the financial clout and the infrastructure to enter the developed world.

The pandemic might prove to be the global health crisis that paves the way for SII to do just this. The big pharmaceutical companies in the West accuse firms like SII of piggybacking onto their costly research to produce inexpensive copycat vaccines. Adar wants to pressure Western companies and governments to start changing the landscape, using the example of Covid-19, and the global need for inexpensive vaccines on a massive scale, to illustrate the flaws in the current system.

Opening up the West would be fantastic for SII’s business and for its owners’ profits. Cyrus Poonawalla does not believe in hiding his wealth. He is candid about his taste for the good life and has a reputation for flamboyance. ‘I am proud of spending the money with which I have enriched myself, without compromising my principles and being ruthless,’ Cyrus told me. He has a reputation for style and enjoys being photographed in the company of glittering international celebrities, or in his trademark hat and long cigar, celebrating his thoroughbreds in victory enclosures at racetracks around the world. His son, Adar, and glamorous daughter-in-law Natasha are often the subjects of glossy magazine features salivating over their jet-setting lifestyle. Cyrus says he sometimes cautions them about their extravagances, but resigns himself good-naturedly to the younger generations’ consumerism. ‘What is life all about,’ he says they believe, ‘if you can’t enjoy your wealth.’ Natasha, born to a Parsi mother and a Punjabi father, is close friends with several Bollywood and Hollywood stars and rivals them in both looks and attire. She figures regularly on the list of the best-dressed women in India. ‘I have been a clotheshorse all my life,’ she once told a writer for a weekend supplement. ‘Dressing is a creative outlet for me.’ But the London School of Economics graduate dislikes being portrayed as a beautifully dressed airhead and party girl. She takes her work as chairperson of the Villoo Poonawalla Charitable Foundation very seriously.

The Poonawallas’ conspicuous consumption extends into various spheres. They are an auctioneer’s delight; once they bid, they seldom quit until they have made the purchase. Apart from an impressive collection of modern Indian art, they have also acquired paintings by the Dutch masters Rembrandt, Rubens and Van Gogh, the great French impressionist Renoir, through to the likes of Picasso and Marc Chagall and the contemporary English artist Damien Hirst. Their opulent Pune mansion is stuffed with priceless artefacts, not to mention racing trophies won by Poonawalla stallions bred at their three stud farms, two of them co-owned with his brother, Zavere. (Horses from the Poonawalla stud farms have over forty years won several Derbies and 364 classic races). Though their home base is Pune, Cyrus in 2015 made a successful bid at an auction for the former palace of the maharaja of Wankaner—a 50,000 square foot palace standing on a two-acre palm-fringed seafront compound in South Mumbai’s trendy Breach Candy. The palace was renamed ‘Lincoln House’ when it was bought by the US government and served as the US consulate in Mumbai for over half a century. When the property was finally auctioned, the winning bid was a reported Rs 750 crore, described by the newspapers as the costliest purchase of a property in India. Thanks to the Indian government’s various interdepartmental wrangles, though, the Poonawallas are yet to take possession of the palace. Still, there are other baubles with which they can console themselves—a Gulfstream jet, a luxury yacht, three aircraft simulators and over thirty supercars, including Rolls Royces, Ferraris, Bentleys, Lamborghinis and several rare vintage models. Adar even modified a Mercedes Benz S Class to look like a Batmobile for his elder son Cyrus’s sixth birthday.

Because of Adar’s love of the deluxe, international jet-setter lifestyle, many observers underestimated his business acumen and ability when he took over as the SII chief executive officer in 2011. Adar proved the sceptics wrong, guiding SII to an over 30 per cent rise in profits, while Cyrus remains the chairman of the company. His father had inducted Adar into the firm as soon as he graduated with a degree in business management from the University of Westminster in England, at the age of just twenty; as Adar turned forty, the number of countries being supplied by SII had grown to one hundred and seventy. In its early days, SII struggled domestically because of chronically delayed payments from government departments. Later, until the pandemic, nearly 80 per cent of the company’s revenues were generated outside India.

When Cyrus was growing up in Poona, he was a little envious of the cars and houses of the two richest Parsi families in town—the Jehangirs and the Jeejeebhoys. The Jeejeebhoys were descendants of Byramjee Jeejeebhoy, a wealthy businessman and philanthropist to whom the East India Company had gifted seven villages covering some twelve thousand acres from Jogeshwari to Borivili, in what later became part of Bombay. The Cowasji Jehangir family also shuttled between Bombay and Poona. Cyrus cites the Jehangir family as an example of being unnecessarily low-key. They did not even care, he says, to use their famous surname ‘Readymoney’ or the full baronetcy title of Sir Cowasji Jehangir. ‘If you have such an illustrious name, why not use it?’ he asks matter-of-factly. Cyrus’s firm belief is that when he donates, as he frequently does, to a worthy cause he wants his family name to be attached to those deeds. Hence, Poonawalla is not an easy name to escape in Pune. For instance, the road leading to his stud farm offices and factory is named ‘Poonawalla Road’ after his ancestor, Dhanjishaw. He pays for private traffic wardens on the long stretch of road so that the family and its visitors enjoy VIP movement privileges. When Cyrus came to Delhi in 2016 for the inauguration of the ‘Everlasting Flame’ exhibition, organised by the School of Oriental and African Studies, London, which he had partly sponsored, he did so in typical Poonawalla style. He sent his personal chauffer with his Rolls Royce to Delhi in advance so that he could travel in the style to which he was accustomed.

Cyrus, unlike some other Parsi industrialists, takes a keen interest in community affairs. In fact, Cyrus has seldom turned down a request from his fellow Parsis. When a former BPP chairperson, Dinshah Mehta, requested that the SII reserve 60,000 vials of the Covid vaccine for Parsis—since the community is an endangered micro-minority and over forty people from the ageing community had died from the virus in the first wave alone, far above the national average, Cyrus instantly acceded to the request. Adar seconded the generous gesture in a tweet, pointing out that it would be just a day’s production. However, since the Government of India is fully in charge of the vaccination drive, a special concession for the Parsis was not possible.

Without doubt, the Poonawallas’ most significant philanthropic contribution is the low price at which they sell their vaccines. It is estimated that two-thirds of all the children in the world born from 2015 onwards have been administered at least one dose of a vaccine produced by SII. Cyrus believes that some thirty million children in poor countries have been saved because of his low-cost vaccines. The pricing policy is a conscious decision not to exploit the health of people for outlandish profit margins. Cyrus’s philosophy in all business dealings, even real estate, is to strike a bargain that pleases both sides. But the low cost of Poonawalla products proved to be a good marketing strategy as well. ‘Everything fell into place,’ Cyrus says. ‘You are saving children’s lives and you are keeping the competition away. There could not be a better way to be proud of making a living.’

PANDEMIC PAINS

RECENT UPDATES OF the Poonawalla story, however, do not paint as rosy a picture as at the start of the pandemic when SII was viewed as the country’s saviour because of its phenomenal production capacity. Public confidence plummeted when Adar Poonawalla flew to London at the beginning of May to join his family, just a day before the UK put India on its red list and banned travellers as the second Covid wave was raging in the country. Adar told The Times, UK, that he had left the country because he felt there was a grave threat to his life in India: “The level of expectation and aggression is really unprecedented.” Prior to the pandemic, 80 per cent of the SII’s sales were from outside India and he was largely insulated from the pulls and pressure of doing business in his homeland. The young CEO was at a loss how to handle threatening phone calls from state chief ministers demanding more vaccine supplies for their respective territories. “Just because you can’t supply the needs of X, Y or Z you don’t want to guess what they are going to do,” he was quoted as saying. Incidentally, the Central Government had awarded Adar grade Y level of security in April because of his threat perception. Adar explained to the Times that it was not possible to ramp up capacity overnight.

Subsequent to the Times interview, Adar clarified in a tweet that he would be returning to India in a few days to review production in Pune. He wrote that he was in London to hold meetings with stakeholders to discuss how to meet the demand for the vaccine. However, his father Cyrus’ innocent explanation to a journalist that he came to London every year for his summer vacation and to attend the Derby in the first week of June only reinforced the family’s jet-setting image.

The Poonawallas seem to have unfortunately become scapegoats for the Government’s initial delay in making firm financial commitments for vaccine orders. By June, the Central Government had once again taken control of the ticklish task of vaccine procurement throughout the country.

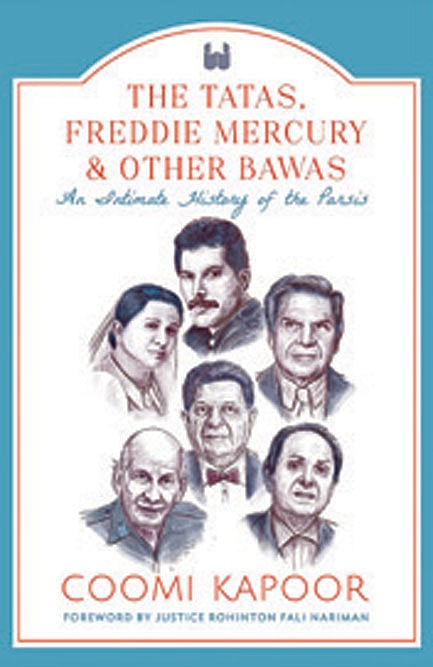

(This is an edited excerpt from The Tatas, Freddie Mercury & Other Bawas: An Intimate History of the Parsis by Coomi Kapoor | Westland | 240 pages | Rs 699)