The Illusion of the Olive Branch

ON MAY 5, MAOISTS IN Chhattisgarh responded favourably to the state government's offer to hold peace talks. A spokesperson of the Communist Party of India (Maoist), the main party of Maoists in India, said that the rebels were willing to talk, but also added that the government's offer was a reflection of its "double standards". The rebel spokesperson was alluding to the party's allegations that government forces have been conducting air strikes through drones on its bastions, a charge the government has denied. A press release issued by the spokesperson said that for the talks to happen, the government must first release its jailed leaders and also withdraw security forces and disband their camps from areas such as Bastar—it is here that Maoists are fighting their last battle against security forces who are increasingly gaining an upper hand in the war against leftwing extremism (LWE). "We are always ready to hold a dialogue provided the government creates a conducive atmosphere for the same," the spokesperson said.

This fresh attempt has come at a time when the CPI (Maoist) is perhaps at its weakest since its formation in 2004. In the last few years, sustained security operations and a string of developmental projects all across Maoist-affected states have led to a major decline in Maoist strength. In Chhattisgarh, where Maoists had carried out some of their deadliest attacks, including the 2010 Tarmetla attack (in which 75 personnel of the Central Reserve Police Force, or CRPF, were killed) and the 2013 Jhiram Valley ambush (which wiped out the state's Congress leadership), they are now on the backfoot, forced to restrict themselves mainly to two districts.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

With the Bhupesh Baghel government in the state offering this olive branch, is there a possibility that there will be some everlasting ceasefire between the government and the rebels? From past examples of such offers and subsequent developments, it seems unlikely that such an offer will bear fruit.

On the Maoist side, such offers are always accepted when the rebels want a breather as is currently the case. Sustained operations and decreasing empathy of the Adivasis in their area of influence have left them worried. On May 9, the Andhra Pradesh police chief, KV Rajendranath Reddy, said that the killing of Adivasis on the suspicion of being police informers and apathy towards the Adivasi cadre were pushing them away from the Maoist party and its leadership. In the last one year, the strength of the Maoist cadre in the state has been reduced by half, rendering its military wing almost ineffective.

In Chhattisgarh, CRPF has set up around 60 Forward Operating Bases (FOBs) inside villages where Maoists used to hold sway earlier. More than half of these have been set up in the last year. Though road connectivity is still far from ideal, the increased security presence has ensured that Maoists cannot operate the way they used to earlier in these parts. As the state continues to increase its dominance, there is no way any state government will agree to a closing of security camps that have been established with a lot of initial struggle, including casualties among security forces.

How did such attempts fare earlier? The biggest possibility of talks between the state and Maoists came in undivided Andhra Pradesh in 2004. It was right after Congress under YS Rajasekhara Reddy (or YSR) came to power in the state after defeating the Telugu Desam Party (TDP). During his campaign, YSR had travelled across rural Andhra, and peace talks with Maoists were part of his manifesto. As YSR took charge of the state, he announced a three-month ceasefire with Maoists and directed police forces to cease all operations against them in June that year.

His decision was influenced by former civil servant SR Sankaran. In 1987, Sankaran was among a group of seven Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officers abducted by Maoists. He went on to forge a friendship with the senior Maoist leadership, which several years later helped him influence YSR's decision. He himself became a part of the group of negotiators who travelled to the forest area a few weeks before the proposed talks and met senior Maoist leader Akkiraju Haragopal, alias Ramakrishna.

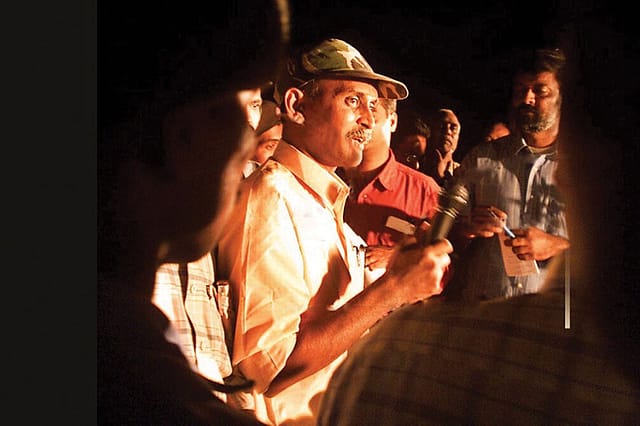

On October 11, a group of Maoist leaders led by Ramakrishna emerged from the forest and was met by negotiators and hordes of journalists and policemen.

Ramakrishna wore a military uniform and carried an AK-47 rifle. When asked if he could wear something else, Ramakrishna replied that he was not carrying anything else to wear.

The Maoist leaders were put up as guests of the state at a government guesthouse. A large crowd had gathered to see them. A year later, a Maoist leader claimed to this correspondent that many senior bureaucrats and police officers had secretly come to meet Ramakrishna to seek solutions to problems in their areas of influence.

The talks took a hit immediately, though. On October 14, as the talks were on, Ramakrishna announced that their party, the People's War Group (PWG) had merged with another party, the Maoist Communist Centre (MCC) to form CPI (Maoist). This, he said, had happened days earlier, on September 21. The talks went on nevertheless. But it was soon clear that there was to be no middle ground at all. Both parties refused to budge from their positions. Maoists refused to accept the government's demand that they lay down arms first.

On the last day of the talks, the issue of land reforms was discussed. Maoists said that the government was not following its own laws pertaining to land redistribution. The government said that it would soon reconstitute a committee to look into it.

Less than two months later, the whole deal came a cropper. Maoists attacked a police party on December 15 in Vishakhapatnam. Days later, in January 2005, the police retaliated by killing several Maoists.

Later, it became clear that neither side was very serious about a genuine peace deal. Maoists used this lull to breathe easy and regroup and look at their strategy in a renewed fashion, particularly in the light of the merger. The state used this opportunity to film leaders and their bodyguards, and others used by senior Maoist leaders as couriers. Many of them, revealed senior police sources, were then lured to give away the location of several Maoist leaders who were then eliminated.

Six years later, in the summer of 2010, another such promising initiative came to an abrupt end. The Delhi-based social activist, Swami Agnivesh, had made headway by convincing the Maoist leadership into holding talks with the Centre. One of their senior leaders, Cherukuri Rajkumar, alias Azad, was negotiating on his party's behalf. It is believed that both parties had agreed on a mutual ceasefire of three days, after which a formal letter was to go from the Union home ministry to CPI (Maoist), inviting them for talks. In his letter, Azad wrote to Agnivesh: "Our party is very serious about bringing about peace, especially at the present juncture when lakhs of Adivasis had fled, and are fleeing their homes; when lakhs of Adivasis are facing chronic conditions of hunger and famine due to their ouster from their lands… one should not be swayed by victories and defeats at this critical juncture in the life of the Adivasi community in our country, but try to create conditions whereby their survival is ensured."

In his response to Azad's letter, Agnivesh, according to Maoist leaders, offered three slabs for the possible ceasefire. It is this letter that Azad was purportedly carrying to the Maoist guerrilla zone in Bastar to discuss it with other leaders. It was there that things went wrong. Azad was allegedly nabbed by security forces near Nagpur railway station on July 1, taken to the forests of Adilabad in Andhra and shot dead. With him a journalist, Hem Chandra Pandey, was also allegedly picked up and killed. The police, for their part, maintained that the two were killed in an encounter in the forest area.

In this episode, it is very difficult to ascertain what could have been the outcome if Azad had reached his colleagues. Back then, Dilip Simeon wrote: "The Maoist party has not spent decades in forests, and lost thousands of leaders and cadres in the process, only to give up their basic goal because some well-meaning peace-loving friends so desire. Furthermore, the Maoist party never had it so big before in its long career in terms of national and international attention, area coverage, acquisition of arms and personnel, and intellectual support. For the more militant sections in the organisation, this would obviously be seen as a victory of the party-line."

More than a decade later, the situation is very different. The "career" that Simeon spoke of seems to be coming to an end, or it may already have ended. Maoists are also aware that any big attack on a state apparatus currently would end up inviting a harsh response from New Delhi—a cost the party and its leadership is definitely not in a position to bear. But does that mean there will be some forward movement on the offer made in Chhattisgarh? That seems unlikely, even impossible.