The Free Speech Question

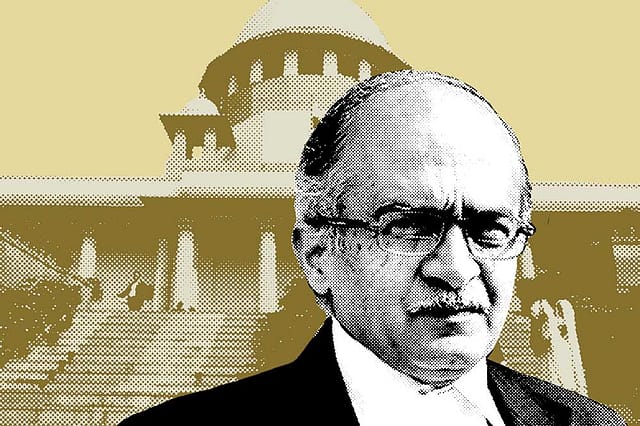

WHEN A BENCH led by Justice Arun Mishra rose on August 20th, after hearing a contempt of court petition against Prashant Bhushan, it was clear that the court had stuck to its guns. It rejected Bhushan's prayer for deferment of sentencing after he was held guilty on August 14th. The court also refused to entertain his plea that a different bench decide on the sentence.

As the proceedings head to a conclusion, a sword hangs over Bhushan's head since the court remains unimpressed by the public campaign mounted in his defence. The court gave Bhushan two days to reconsider his statement. As of now, the lawyer remains unapologetic for the two tweets he made for which the court held him guilty of contempt of court. In a way, the court has displayed remarkable lenience towards him. On August 20th, Justice Mishra said: "There is no person on Earth who cannot commit a mistake. You may do hundreds of good things but that does not give you a licence to do 10 crimes. Whatever has been done is done. But we want the person concerned to have a sense of remorse."

Bhushan apologised for a portion of his tweet on Chief Justice of India (CJI) AS Bobde, riding a Harley Davidson motorcycle. In another tweet, on June 27th, he had said: 'When historians in future look back at the last 6 years to see how democracy has been destroyed in India even without a formal Emergency, they will particularly mark the role of the Supreme Court in this destruction, & more particularly the role of the last 4 CJIs.'

The court, in a 108-page judgment, analysed the law of contempt at length and Bhushan's tweets. When it became obvious that the judges were in no mood to ignore Bhushan's transgression, a campaign of sorts was mounted to save him. A number of arguments were made in op-eds, letters and statements. Most rested on the alleged 'destruction of democracy' and the 'chilling effect' his sentencing would have on free speech. Barring one technical argument—that the consent of the Attorney General was not taken as was required under Rule 3 of the Rules to Regulate Proceedings for Contempt of the Supreme Court, 1975—everything else was about freedom of speech. The consent issue was explained at length by the court in its judgment and was not considered an impediment in proceeding against Bhushan.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

That is where the substantive issues around the case come to an end. The judicial system has a chain of appeals—starting from the lower courts all the way to the Supreme Court—in case a person feels he has not received justice. Even in the apex court, there is a provision to file a review petition, a highly unusual remedy since once the court delivers a judgment, it is binding, there being no further court for appeal. Bhushan has chosen to opt for a review petition but that is where there is a twist in the story.

On August 20th, Bhushan through his lawyer not only sought deferment of sentencing by the bench led by Justice Mishra but also sought that the sentencing be carried out by a different bench. (Justice Mishra is set to retire in early September.) This was as good as expressing a lack of confidence in the Justice Mishra bench. For anyone familiar with the working of the judicial system, this is as good as trying to pick a bench for hearing one's case. In the event, the court rejected this outrageous demand.

This extraordinary demand should be seen against the background of events of the past years. Since the Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association versus the Union of India case of 2015 that held the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC) to be unconstitutional, an impression has been created that the judiciary is allegedly 'deferential' to the executive. It is another matter that after that period, there have been a number of instances where judicial decisions—from high courts to the apex court—have gone against the Union and state governments. What has changed is the inability of certain lawyers to get decisions of their liking in many politically sensitive cases. This has been interpreted—as Bhushan did in his second tweet—as the judiciary weakening democracy in India. The court rightly noted this as an 'attack' on the Supreme Court that could lead to "A possibility of the other judges getting an impression that they may not stand protected from malicious attacks, when the Supreme Court has failed to protect itself from malicious insinuations, cannot be ruled out." The court concluded: "As such, in order to protect the larger public interest, such attempts of attack on the highest judiciary of the country should be dealt with firmly."

The case raises an important question: Can freedom of speech be used to mount an attack on an institution which is the ultimate protector of free speech? The bench led by Justice Mishra expressed the fear that this is indeed the case. In contrast, Bhushan— through his tweets, his submissions in the contempt case and his refusal to apologise to the court—thinks otherwise.

No institution can survive unless it allows criticism against itself. Otherwise mistakes and course correction will become impossible. India's Supreme Court certainly allows ample criticism. So far, there has been not a single instance when fair criticism of the court has led to punishment under contempt of court. Analysis of infirmities in judicial decisions is a regular feature in the Indian press and TV debates. What has happened in Bhushan's case is far removed from all this. The attempt at mobilising public opinion against the court and statements by 'eminent' lawyers and retired judges were not about pointing out mistakes made by the court but forcing it to let Bhushan off the hook. That the court stuck to its guns preserves its ability to dispense justice impartially and does not undermine it. What makes it remarkable is that the three judges stuck to their decision despite intense outside pressure to abandon it. Famous lawyers—whatever be their record in trying to secure justice—are just like any other individual before the court. Trouble begins when such individuals forget that and think they are on a different footing. What Bhushan sought on August 20th—deferment of sentencing and sentencing to be carried out by a different bench—conveys that message clearly.

All this is in contrast to another recent contempt case—that of CS Karnan—a serving judge of the Calcutta High Court. He was convicted of contempt of court in May 2017 and had to serve a six-month prison term. At that time, there was near unanimity that Karnan deserved to be punished. Many—including Bhushan—held that his conviction was right. At that time, there were no op-eds in support of Karnan—a Dalit—that said freedom of speech was endangered or that the punishment meted out to him was unfair.

For a long time, during which the executive was weak due to a fractured political landscape, the apex court and the high courts stepped in and sorted out a number of issues, ranging from environment protection to a vast expansion of fundamental rights by interpretation, tasks that originally belonged to the executive and the legislature. Since the NJAC judgment, a re-equilibration of sorts is on, one in which the court is an active participant and not a mute spectator as has been alleged. While the process is on, certain influential lawyers think that they can continue getting the court to intervene in matters where the executive has filled in the earlier gap. The Bhushan case is a small manifestation of this overall process.