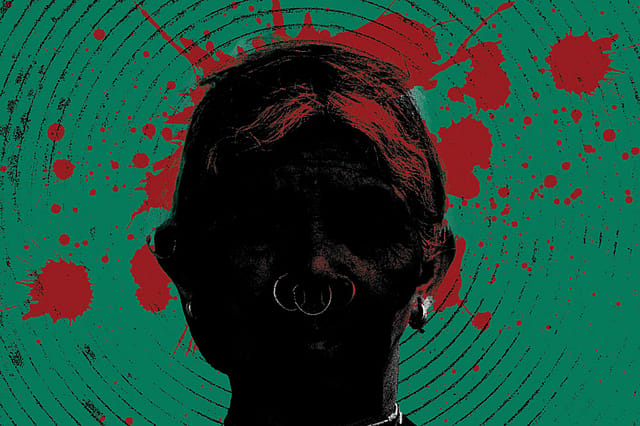

The Evil Eye

MERI ROOH KAAP UTHTHI HAI, USS din ke baarein mein soch ke (I am scared to death thinking of that dreadful day)," a young man recalls while narrating the cold-blooded murder of an old woman in his neighbourhood on a chilling November day of 2022 at Baihatu village in the Tonto subdivision of Jharkhand's Singhbhum district. The woman had to die because she cast an evil spell on the rest of the villagers, the elders had decided.

The elders here comprise a group of men who have the power to preside over the destiny of the others in this remote countryside. In this backward tribal hamlet frozen in time, most residents are either illiterate or semi-literate. Patriarchy here isn't a seminar-room expression in a plush 21st-century setting. The woman wouldn't die an easy death. She would be beaten until she fell unconscious; when she regained consciousness, she would be paraded naked across the village alleys until the last ounces of her strength ebbed away. And then she would be burnt to death. Unlike Joan of Arc at the stake in 1431, nobody would ever bring her name up and canonise her centuries from now because she lived and died a nonentity, a victim of superstitions, and the cunning of men whose aim possibly could have been her property.

A year earlier, in broad daylight, on an October afternoon, in the Potka block of East Singhbhum district, Jharkhand, another old tribal woman was smeared with urine and faeces, thrashed with sticks, stripped naked and paraded around the village on a bullock cart. She was found dead in her mud house the next day. In the case of young women, rejecting sexual advances may mean being branded a witch.

My ethnographic studies across Jharkhand, Odisha, West Bengal, and Bihar since 2021 have put me face-to-face with 21 such instances of tribal women being accused of possessing black magic charms and later killed. All those who have died perished at the hands of their communities. It meant the news of the killings never attracted much attention, not to talk of an outcry over gender-based crimes. Police forces in these areas are unable to take action due to the local customs and silence around such killings. In the absence of official complaints and police inquiries, such acts of violence are normalised, except for the occasional revelations from the young man quoted at the start of the story. This research has also brought me in touch with a handful of women who have survived by a whisker and lived to tell the tale.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Simply put, in tribal India, especially in the eastern Indian states mentioned here, the charge of witchcraft continues to be employed by men to grab land, money, and other resources from women who are labelled "dayan" or "dakan" (witch) before they are eliminated. Some of the victims include a woman who had sought postpartum treatment at a hospital, another who lit the funeral pyre of her mother, and then a woman who married the man she loved, of course, from the same tribal community. They were mostly burnt alive. The younger ones were gangraped before they were killed.

Their crime? They dared to challenge the power dynamics in their communities. The result: they were persecuted as wielders of black magic, a patriarchal ruse weaponised against women since the dawn of time to rein in inconvenient ones. Such brutalities in the country's hinterland serve as a reminder of how women's position in a section of society continues to be precarious, and that any deviation from their prescribed roles transforms them into targets.

The connection between femininity and accusations of witchcraft has roots in most parts of the world. In the 17th century, Salem, Massachusetts, US, witnessed a series of witch hunts. Following public "witch trials", over a dozen young girls were burnt to death there. Throughout pre-modern Europe and colonial America, this savage practice was routine, especially amidst socio-religious turmoil, epidemics, and largescale property conflicts. Similarly, in Indian folklore, we have heard of the daini and the pishachi using black magic to wrongfully possess, corrupt, and pollute their targets. Such gendered powerplay is seen in the occurrences of "witch hunts" in contemporary tribal India, too. Notwithstanding the government's best efforts to close the gender gap, some cultures are bound by old habits that go by the name of traditions or customs.

The targeting of tribal women by their own men has persisted, but increasingly for motives other than superstition and religious or cultural faith. As recently as October 2021, a 55-year-old tribal woman from Mangadu village, Jharkhand, was murdered by two youths after the duo claimed she was a witch. As usual, she was mercilessly thrashed with sticks and paraded naked before she was killed. Unexpectedly, though, the incident caused a furore.

Tribals in these parts of India typically are closed forest groups who worship nature, animals, and other totems. Being traditionalists, they understand nature and ecology through methods of observation, which may not always be scientific. As a result, any ecological imbalance is perceived as someone's evil spell. Crop failure, land issues, floods and droughts, and incessant rains are all blamed on the evil eye. Literature suggests that tribal civilisations in certain belts of India had a higher prevalence of patriarchal institutions and therefore, historically, there has been a strong link between allegations of witchcraft and gender tensions in indigenous groups. Low literacy rates and significant backwardness in these locales haven't helped the tribals change with the times. Therefore, they end up behaving in the same fashion as people did in pre-modern societies. However, the modern witch hunt isn't about superstitions and tradition alone, but about a certain power play that comes into effect to silence women.

Witchcraft as a practice works in consensus with both mass approval and mass involvement, mostly embedded in norms of adherence to traditional and cultural affiliations. Traditionally, across cultures, the so-called witches are first given a bad name and then treated as fair game. As we know from literature, tribals believe that women who have the power of black magic can cause crop failure, unforeseen death in a family, ailments, and the reversal of fortunes, meaning they can turn a rich man poor. Once a woman is identified as a witch, she is first made a village outcast, relegating her to living on the periphery of her village. Killing them is not always the preferred norm, but as it emerges now, the number of killings is on the rise. None of this is without a reason.

My study puts the spotlight on the manipulative nature of men in these societies.

A not-so-often acknowledged but widely practised phenomenon is the blind belief in the ojha, or a pandit. These men position themselves as experts who claim to communicate with ghosts and spirits. In Purulia district of West Bengal, my team and I met a woman who was accused of being a witch. She said on condition of anonymity, "He [the ojha who came to her village to meet her] asked me if I could eat rice without experiencing any hiccups. Do I feel pain when I perform domestic chores, like washing clothes or grinding lentils on the sil-batta [stone mortar pestle]? When I said I had no difficulty, he looked grim. The ojha then took a drop of my blood using a pin and examined its colour. Then he said he will help me become normal again."

The ojha then walked out and addressed the village crowds saying that her blood was deep maroon in colour, and that her blood flow wasn't "fast enough". His interpretation was that maroon is close to black, and that she needed to be "treated" by him.

ESSENTIALLY, WHAT HE did was to scare families in the village and extract money to perform pujas that can "protect the area from the evil eye" of the alleged witch. The illiterate villagers look up to the ojha and offer him presents because they believe he is risking his life for the good of the village. It is an irony that this village is so poor that most people here are anaemic from malnourishment. The womenfolk here have low bone density and suffer from anaemia once they cross age 30.

From 2017 to 2022, at least 21 cases of tribal witch hunts have been reported in the states of Jharkhand, West Bengal, and Odisha. First, women are classified as witches to settle personal grudges or dishonour to a family apart from the motive to secure their land. The "witches" are often single and/or widowed and have some land in their possession. Their close relatives are the ones involved in the whole exercise of branding them as witches and persecuting them.

The various instances of witch hunts in tribal societies involve an undercurrent of power and legitimacy, projected to be drawn from ritualistic purity. Take the case of a love marriage between a tribal man and woman from Van Pokharia village of Odisha in 2021. The village leaders demanded compensation of approximately `20,000 for rice, chicken, sheep, etc, to remove the 'pollution' caused by a modern love marriage.

The violence unleashed on so-called witches can be divided into three categories: normal, harsh, and extremely severe. The first involves mild beating, tonsuring, solitary confinement, blackening of the face, and so on. Then comes an economic boycott, making the woman walk naked, thrashing with sticks, etc. Most severe punishments include gangrapes and mob lynching. The last category is now the most frequent. Worse, witches are often put to trial by forcing them to consume human excreta and urine to see what happens next. In some cases, their teeth and nails are pulled out. Most of these brutal incidents are reported from Odisha, Jharkhand, and Bihar.

A field study conducted by the National Confederation of Dalit Organisation (NACDOR) highlights two heart-wrenching stories of women branded as witches who however survived their ordeals.

Munni (name changed) is a 40-year-old from Lakhanpur village in Dumka district of Jharkhand. Married with four children, she was branded a witch by village elders. Her family was engaged in casual labour. One morning, the family woke up to realise that Munni was blamed for the death of a neighbouring boy. The elders alleged that she practised black magic and had cast her evil spell on the deceased boy. She was put through a well-planned and structured boycott, alongside torture like beating and physical abuse. She was forced to consume human excreta and urine as part of her "purification process". Complaints to the police did not help, and the villagers finally decided to make the family outcast. Munni escaped death, although social and economic boycotts continue.

Anita Devi (name changed) was once respected for being smart, hardworking, and knowledgeable. Her woes surfaced after she was accused of causing the death of her sister-in-law's child. The accusation against her was that she failed to save the child despite being intelligent and of quick wit. She was subjected to physical torture. An intervention by the police pacified the elders for a few days. Soon, her own husband joined the others in beating her up in public. Unable to bear the ordeal any longer, she fled the village leaving her children behind.

The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) data reveal the killings of 310 "witches" between 2018 and 2021 nationwide. While Odisha recorded 2,500 such killings between 2000 and 2016, Jharkhand saw 377 "witch murders" from 2015 to 2022. Even though steps have been taken by social groups and authorities to stop this, the practice still thrives among some of India's most backward tribal groups.

District administrations must chalk out comprehensive programmes to weed out the practice and launch effective awareness campaigns. However, officials aver that ignorance and backwardness compound the problem among the tribals who stick to old traditions and refuse to treat women with respect—although a few bravehearts are working towards the uplift of these tribal women and to save their lives. Traditional healers also add to the confusion by blaming the deaths on "witch exorcism" when people treated by them die. The sheer brutality of killings of women after hanging a bad name on them suggests that transforming such societies through outreach schemes and campaigns is bound to be a Herculean task.

(Aditi Narayani Paswan received field assistance to write this essay from Sangya Dubey, a doctoral candidate at Jamia Millia Islamia)