Jon Fosse: Master of Mystic Realism

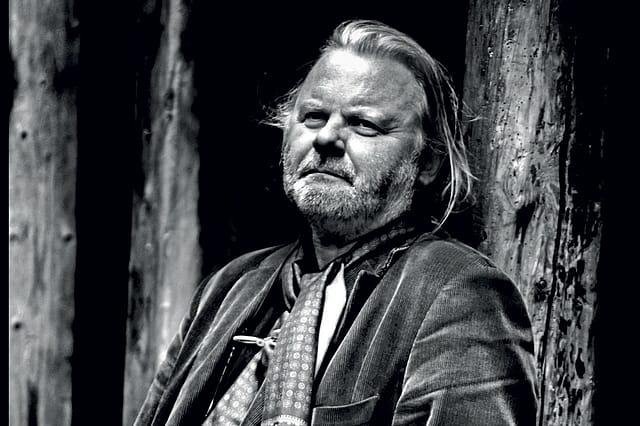

JON FOSSE MIGHT not be an easily recognisable name to Indian readers, but in the Scandinavian and European literary world, he is the "Beckett of the 21st century" or the "Fosse phenomenon". He has won numerous awards; including the International Ibsen Award and Swedish Academy Nordic Prize. His corpus includes 40 plays, novels, poetry collections, essays, translations and even a hymn. Having grown up on a small farm on the west coast of the country, the hum of the sea echoes through his work. He writes in Nynorsk (or new Norwegian) and not Bokmål, the dominant language of the country, which has been influenced by Danish. This itself is seen by many as a political act. The books that have influenced him the most include Franz Kafka's The Trial, The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner, Collected Shorter Plays by Samuel Beckett, Mrs Dalloway by Virginia Woolf, and the Bible, which he spent 11 years translating to Norwegian. He has been awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, 2023, "for his innovative plays and prose which give voice to the unsayable."

What might this "unsayable" be? We can best get an idea from his 1,251- page magnum opus, completed in 2021, titled Septology. It includes three parts: The Other Name, I Is Another and A New Name. The English translation by Damion Searls was brought out by the prestigious Fitzcarraldo Editions, which has published other Nobel Prize-winning authors, such as Annie Ernaux and Svetlana Alexievich. To read Fosse is to initially be disoriented. His sentences run on for pages, and the three parts of Septology are set just within the timespan of a week. It takes a while to get a grip on the elderly artist Asle speaking to himself as another person. All three parts start and end with the similar premise; that of an artist painting two strokes, one purple and one brown as a diagonal cross (St Andrew's Cross) and wondering how to complete the painting, and the books conclude somewhat in mid-prayer. The opening sentence of The Other Name runs for 34 lines before a question mark gives the reader a pause. The endless sentences plunge the reader into Asle's inner turmoil; "Asle thinks, and he thinks that thought again and again, it's the only thought he can think, the thought that he's going to disappear into the sea, into the nothingness of waves…" The artist looks back at his life in fragments of memory, playing on the beach as a child, meeting his wife, leaving the Church of Norway and becoming a Catholic, wondering if he should go out in the snowstorm to walk his dog. Through it all, his main preoccupation is with the meaning of god and the reconciliation with fate. It is a book that conveys that the world is, indeed, a dark place, but that the light does eventually shine through.

It's A Big Deal!

30 Jan 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 56

India and European Union amp up their partnership in a world unsettled by Trump

In an interview, Fosse has said, "I try to write about the mystery of life. I am not looking for answers in a simple way; I want to celebrate the enigma." This enigma can be seen in works of his like A Summer Day that was staged to acclaim in New York in 2012. The play is an apt example of Fosse's existential angst. The plot, in a sentence, is about a wife whose husband takes his boat out on a summer day, and never returns. The play revolves around the wife waiting, and wondering about the many what-ifs; will he return, where is he, could she have stopped him from leaving, or did he leave because of her? The play was recognised for keeping viewers on edge and for its "icy discomfort" (The New York Times).

The Swedish drama critic Leif Zern writes in the book The Luminous Darkness: The Theatre of Jon Fosse that the core of Fosse's dramatic work is "mysticism, the fragile balance between emptiness and meaning." The 64-year-old's plays grapple with ideas of home and belonging, who leaves; who is left behind; the unpopulated countryside; and the gulf between the urban and the rural. The Nobel Prize is not only a celebration of Fosse's themes but also his treatment of them. He artfully reduces both language and action. He uses simple plots to express human nervousness and powerlessness. By disorienting the reader, he shows us how unmoored we are, and thus our need to find greater meaning.