Gearing Up for the Big Gig

The Centre is formalising measures to protect the rights of platform economy workers

/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/BigGig1.jpg)

(Illustration: Saurabh Singh)

GURUGRAM-BASED DELIVERYMAN Rajat Gupta (named changed) says that he is paid ₹40 per delivery by a reputed grocery-shopping app—the company that employs him to handle their dispatches. He stays awake at odd hours to land what he describes as “two deliveries on an average a day” in NCR (National Capital Region), and pays for the fuel required for his two-wheeler, which he bought second-hand.

A Bengaluru-based coder, who, unlike Gupta, does white-collar gigs that he finds through a multinational app popular worldwide, says that he earns much less than he used to 10 years ago because of a raft of reasons. This includes the 10 per cent service fee he pays to his employer—who, interestingly, calls him a partner or a micro-entrepreneur. Because of the fear of negative ratings by consumers, he also has to put up with difficult tasks, short deadlines and late hours, not out of choice but out of necessity to make a living wage and to keep his ratings high on the app. He also worries about not being paid—his company is notorious for withholding wages, claiming coding errors.

For their part, employers—the aggregators—argue that treating contractual workers as employees will prove to be financially unviable. As of now, the platform economy—which the UK government describes as a segment that “involves the exchange of labour for money between individuals or companies via digital platforms that actively facilitate matching between providers and customers, on a short-term and payment-by-task basis”—accounts for a small chunk of the total workforce, but it is expected to grow worldwide as well as in India. According to a Nasscom-Aon report, the gig workforce here is projected to reach 2.5 crore in another five years, up from 70 lakh in 2021. More importantly for India, the majority of the workers consider their gig work “full-time” as opposed to temporary ones in the West.

It is in this context of rising to the challenge of managing the aspirations of the workforce in the platform economy—which is marked by the proliferation of new technologies that are routinely making several jobs redundant and others cheap—that governments across the world are conceptualising frameworks to protect employees. Some of the big players in the platform economy in India are Uber, Ola, BluSmart, Swiggy, Zomato, Urban Company, BigBasket, Porter, Zepto, Amazon Flex, Dunzo, UpWork, Fiverr, TatD, and so on.

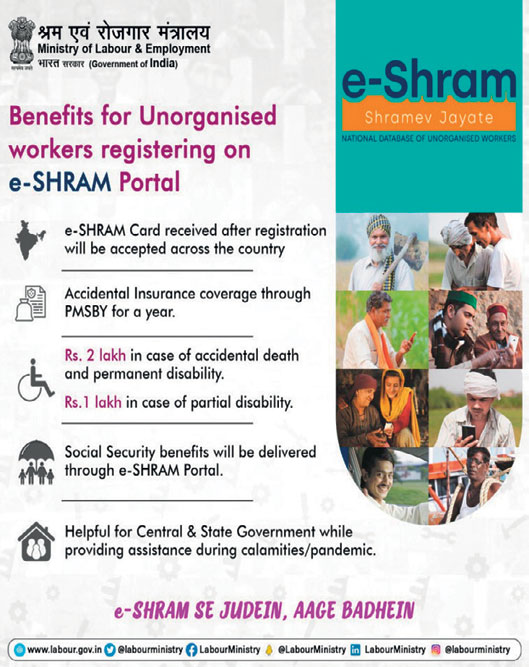

The latest announcement from the Union labour ministry is that it has asked technology-based platforms and aggregators to get all gig workers engaged by them to register on the e-Shram portal, a centralised database of informal workers, where they can avail of health insurance and other facilities, including unemployment benefits, maternity benefits, and accident injury coverage through the Employees’ State Insurance Corporation (ESIC).

As of now, gig workers are eligible only for minimum social-security benefits. A July 2024 statement from the government stated that “for the first time, the definition of ‘gig workers’ and ‘platform workers’ has been provided in the Code on Social Security, 2020.” Code on Social Security is one of the four codes that the Union government has brought in with the aim of consolidating previous labour laws. These four deal with wages, social security, industrial relations, and occupational safety.

In an interview to Open, CK Saji Narayanan, former national president, Bharatiya Mazdoor Sangh (BMS), terms this inclusion of gig and platform workers in the Code on Social Security as a “partial victory of sorts”. He says that what trade unions like his are fighting for are decent working conditions for the workers. BMS, he says, workscloselywith the InternationalLabour Organization (ILO) in securing a fair deal for the platform workers. He said BMS raised the issue in the recently held BRICS meet at Sochi in Russia, too.

ACCORDING TO REPORTS quoting sources in the labour ministry and from people close to the matter, Union Labour Minister Mansukh Mandaviya launched trial runs in partnership with platform aggregators to get workers registered on the e-Shram portal. They also said the ministry has issued an advisory with a standard operating procedure outlining aggregator responsibilities. An IANS report said that, to assist with the onboarding of workers and aggregators, a toll-free helpline (14434) has been set up to provide information, guide registration, and resolve any technical issues encountered during the process. Another report said that according to a proposed policy, aggregators will have to contribute 1-2 per cent of their revenues to a social security fund and an equivalent contribution will likely come from the government.

People close to the matter say that what necessitated this move by the government was also concerns about occupational safety and health (OSH) of gig workers, especially those in delivery and transport sub-segments who work under tremendous stress and in tough conditions. Some of these blue-collar and grey-collar workers are also skilled, such as those in caregiving and beauty services.

Echoing the concerns of Saji Narayanan, Rikta Krishnaswamy of the All-India Gig Workers’ Union and Sunand of the Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU) aver that the basic problem arises from the refusal of platform aggregators to address workers as employees, and instead, referring to them as partners. “Any social security scheme is welcome,” Sunand tells Open. He asserts that what often adds to the woes of employees in the platform economy is that besides their jobs being precarious, the reasons for their termination—which is often euphemistically called deactivation because it is all about not having access to your account in an app—is never clearly spelt out. The fact that consumers can decide your future in a job—with no grievance redressal mechanism in place—makes working conditions tense and grim, he argues. “In addition to that, your ratings are what determine your job stability or instability. Workers’ rights are of no concern for any of these players,” Sunand adds. He emphasises that in the wake of complaints of manipulation of algorithms by aggregators, they must be asked to share such details with the government or any authority in case there is a dispute. Similarly, he says that there must be more transparency in the financial transactions of these aggregators. For her part, Krishnaswamy notes that new laws need not be brought in when existing laws can protect the rights of the workers. She says that the Shop and Establishment Act is one of them.

To be fair, some of the platform aggregators that Open spoke to say that they have already implemented social-security schemes for their “partners”. Urban Company says that it “voluntarily provides life insurance cover worth ₹6 lakh, disability cover worth ₹6 lakh, accidental hospitalisation and more”. It lists out pro-employee measures, including health insurance plans, free medical consultations, and so on. In a statement, the company adds, “For top-performing partners, the policy also provides family medical insurance for spouse and two children and up to 12 free medical consultations per year. In FY24, over 1,800 service partners benefitted from these insurance covers.” Amazon India and several other companies didn’t respond to repeated pleas for comments seeking details of their social-security plans for their workers.

ILO is currently busy working on a draft in the run-up to its June 2025 meeting to discuss the issue of social security for gig workers. Unionists here hope that ILO comes up with a “convention” that is binding on all countries, instead of making mere recommendations that may not have a similar impact.

Several workers that Open spoke to say that, while they appreciate the flexibility of gig work, they tend to be underpaid and are forced to stay logged on for long hours amidst anticipation and stress. A few overseas scholars have invoked Karl Marx to state that his prophecies have not gone wide off the mark. In his paper titled ‘Uberization of Labor and Marx’s Capital’, Brazilian economist Guilherme Nunes Pires writes, “Although the combination of ICTs [information and communication technologies] and decentralised labour activities produces new business models through digital platforms, the central specificity of Uberization of labour remains explained by Marx’s critique of political economy, that is, the necessity of capital to reduce labour costs and amplify its exploitation.”

According to sources in the labour ministry and people close to the matter, Union Labour Minister Mansukh Mandaviya launched trial runs in partnership with platform aggregators to get workers registered on the e-shram portal

However, US-based entrepreneur-turned-academic and author Vivek Wadhwa sees rays of hope in India. Gig economy companies go to great lengths to cut costs in the US, often manipulating algorithms to their advantage, he points out. “Unfortunately, there’s little hope for reform here in the US, as the tech industry wields immense power and heavily influences policymakers,” he says.

He goes on, “However, in India, there’s still room for optimism. The government has been establishing checks and balances through initiatives like ONDC [The Open Network for Digital Commerce], which was designed to foster fair competition. States like Kerala are even stepping up with alternatives like the Kerala Savaari app, offering market-driven solutions that prioritise both drivers and consumers.” Thus, he believes, creating market alternatives to the big tech companies is the best way of dealing with the problem of worker exploitation. Another notable finding from a study by the Institute of Social Studies Trust is that NGO-backed platforms are far more considerate of worker rights. Cab-hailing apps for women like TaxShe and Sakha not only extend social-security benefits, they also ensure decent wages and hours, and allow women workers the flexibility to manage their care work at home.

Bengaluru-based writer and former MNC banker Sreejith Sreedharan, author of Future of Work: AI in HR, says that the Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Maan-Dhan (PM-SYM) scheme is a step in the right direction towards upholding the rights of gig-economy workers. He warns against getting carried away by certain “empowering designations and phraseologies” that often serve as distractions, particularly for platform workers in India, who remain vulnerable due to the absence of legal protections. “Many gig workers are exploited by organisations, as there are currently no robust frameworks or laws safeguarding their interests.”

He adds that the contribution of gig workers to India’s evolving service economy is significant and cannot be overlooked. “As the service sector has grown, so too has the gig economy. To harness this potential, governments and industry bodies must increase efforts to create supportive environments for gig workers. Enacting a comprehensive legal framework is a critical gap that needs to be addressed.” He argues that the factors driving the gig economy are both economic and rooted in the evolving nature of work. For organisations, gig workers can improve the bottom line, particularly in times of economic uncertainty, hesays. Forworkers, gigworkreflectsboththechallengesofa competitive job market and a desire for greater control over work-life balance, Sreedharan adds.

In emerging economies like India, which has a large working-age population, the gig economy is likely to experience steady growth for at least the next decade, he says. “The advent of AI is further expanding opportunities for gig workers by offering more specialised roles on digital platforms. New job categories such as content creation, chatbot development, AI training, and data annotation are increasingly available to gig workers. AI-powered algorithms also enable better job-skill matching, which enhances productivity and enables gig workers to find more relevant work,” Sreedharan explains. He says that the future of gig work in India looks promising, but realising its full potential requires proactive efforts.

He sums up, “The government and industry bodies must act swiftly to create supportive frameworks and policies that can help workers and organisations alike capitalise on these opportunities.”

Meanwhile, a few state governments have come up with laws and initiatives to safeguard the rights of gig workers. Several Delhi-based government officials surveyed by Open for comments state that any new initiatives should be done in consultations with players in the platform economy since it is a growing segment open to vulnerabilities and shocks caused by stock markets.

Rikta Krishnaswamy is of the view that the new rules called Platform Work Directive (PWD) in the European Union is a model worth following in India, too. This new law has come up with a clause titled “presumption of employment”—which means workers shall be legally presumed as employees if their link with their platform meets at least two out of five specific criteria, which include the following: control over pay and working hours; performance monitoring; task allocation and distribution; control over working conditions; and restrictions on work organisation.

With the government determined to address the employment problem and improve the working conditions of those in the gig economy, looks like it is time for employers to work towards building a more collaborative business model.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Cover-OpenMinds2025.jpg)

More Columns

Google Goes Nuclear Open

PM Modi marks 10 years of Digital India, highlights transformation Open

Puri Marks Sixth Major Stampede of The Year Open