Free PDS rations is good economics and smart politics

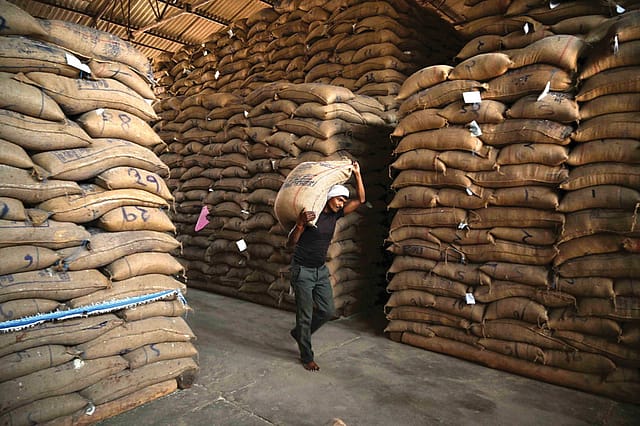

Just ahead of the Centre's decision in late September to extend free rations to 80 crore beneficiaries by three months at a cost of Rs 44,672 crore, finance ministry officials weighed the utility of the scheme – whether it continued to serve the purpose for which it was envisaged at the start of the Covid pandemic in April, 2020.

The call was largely political, even as it became apparent that while the pain of Covid had eased a family of four drawing 50 kg of food grains a month, it raised the question whether this was required besides a rising bill. At least some of the food grains supplied under the scheme and the regular allocation under the national food security act were finding their way into the open market for a profit.

The dilemma was challenged with some arguing that the free rations were an important factor in BJP's success in the Uttar Pradesh election held in February, 2022. Also, withdrawing a benefit is never easy given the populist appeal of a free ration scheme. Government also presented the scheme as evidence that it had protected the poor against loss of incomes due to the economic shock of Covid.

In deciding to make food grains distributed as normal rations under the National Food Security Act (NFSA) free and simultaneously discontinuing the additional rations scheme, the government devised an elegant solution to an economic and political challenge. On the one hand, it has freed itself from the additional burden that saw expenditure on the PM Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana grow to Rs 3.7 lakh crore with Friday's cabinet decision expected to save an estimated Rs 2 lakh crore next year.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

On the other hand, the decision will help buffer the government against the charge that it has withdrawn a benefit for the poor at a time of high inflation, which is likely to remain so in 2023. Though India has not seen the inflation levels as in many developed and developing nations, the price rise is always a politically sensitive issue.

The Centre's call will serve some additional purposes too. On a visit to Telangana in September, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman pulled up a district collector who could not explain why Prime Minister Narendra Modi's picture was missing from a public distribution system (PDS) shop. The official fumbled when Sitharaman asked how much of the subsidy burden was shouldered by the Centre and state respectively.

Answering the question, the Finance Minister said the rice cost Rs 35 a kg in the open market. While the Centre paid Rs 30, the state bore Rs 4 and Rs 1 was charged from the beneficiary. Now that the Centre has taken over the entire burden, there is no room for a state government to chip in with a minor amount and claim credit for the same. This was a major bugbear for BJP state units seeking to capitalize on the Centre's scheme.

The Russian war on Ukraine has led to inflation spiraling across the globe and India is no exception. Prices will remain a talking point in 2023 as well and an alert government would take some precautions on this score. The decision to distribute completely free rations under the NFSA to over 81 crore people at 5 kg per individual is intended to protect the poor and also buffer the Centre from the political impact of inflation that can always lurk around the corner.

When Covid began to tighten its grip on India, the Modi government decided not to succumb to the herd mentality and announce direct cash infusions or doles except for the poor. There were limited transfers to women Jan Dhan account holders and the elderly. There were no handouts to businesses despite several Indian and foreign (many of Indian origin) experts advocating such assistance. Instead, the government facilitated working capital for businesses, ensuring a degree of accountability and income generation. Prime Minister Narendra Modi was clear that India did not have the luxury to print money and it would not prove useful either.

When it came to providing direct relief, the Centre concentrated on the poor who would be most affected by economic activity coming to a halt as it did when a tough national lockdown was announced on March 24, 2020. The strategy worked and India did not witness large-scale social unrest that would have surely followed had there not been food on the table for millions. Businesses too did not just sit on the money or pay down debt as they might have if they had received dole. The decision to offer working capital was well thought out as even Rs 500 a month deposited in Jan Dhan accounts was not used up. In times of grave uncertainty neither the rich nor poor would spend.

The decision for a free ration under the PDS, despite its apparent populism, is an economically sound step. The next will be to scan the list of NFSA beneficiaries that currently include 75% of India's rural and 50% of urban population to focus benefits more productively on those who really need help.