Anatomy of a Dispute

Behind the Assam-Mizoram violence lies a shrinking resource and a lack of mechanisms for institutional resolution

Siddharth Singh and Amita Shah

Siddharth Singh and Amita Shah

Siddharth Singh and Amita Shah

|

06 Aug, 2021

Siddharth Singh and Amita Shah

|

06 Aug, 2021

/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Assam1.jpg)

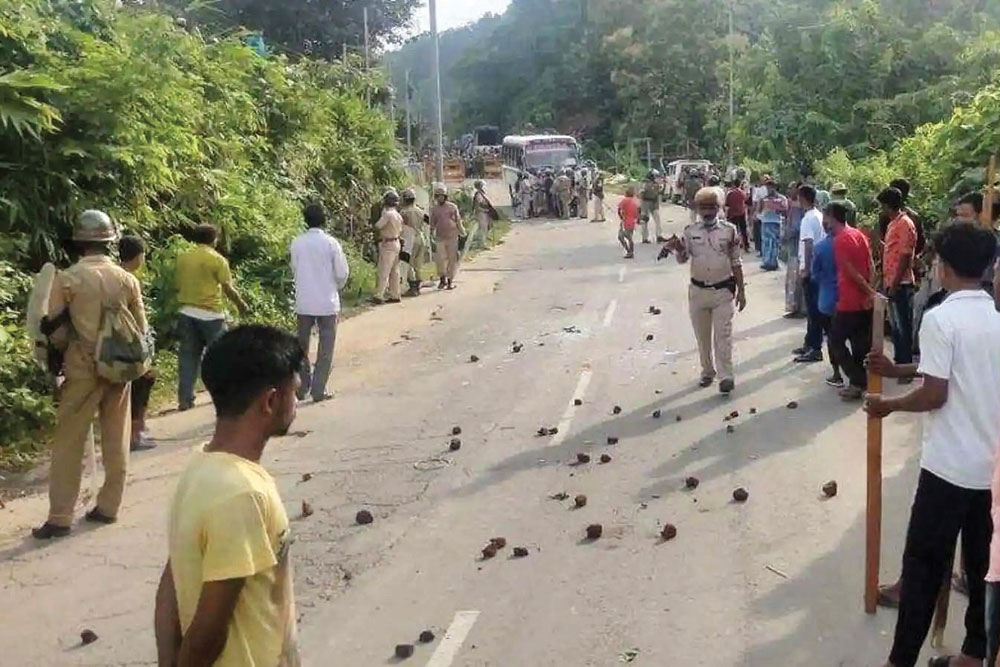

Violence along the Assam-Mizoram border in Cachar district, July 26

BOUNDARY ROWS BETWEEN states turning violent are nothing new in the Northeast. But when an exchange of fire between policemen from Assam and Mizoram turned deadly near the town of Vairengte on July 26th, the country woke up to a new reality of its constituents picking up arms against each other.

The death of five Assam policemen led to a series of charges and counter-charges by chief ministers of the two neighbouring states. Matters did not end there. Assam issued a travel advisory for its residents to avoid Mizoram while Mizoram accused Assam authorities of blockading National Highway 306, a vital link that brings supplies to the state. Both states lodged FIRs and Assam Police even sought to question K Vanlalvena, a Rajya Sabha MP from Mizoram, for a provocative statement.

Then suddenly, two days later, the two chief ministers began to cool tempers in conciliatory messages on Twitter, a stark contrast to their pronouncements on the medium just days earlier.

Both chief ministers—Assam’s Himanta Biswa Sarma and Mizoram’s Zoramthanga—told Open they were hopeful that the August 5th meeting in Aizawl between the two sides would pave the way for a resolution. Sarma had earlier announced that two ministers of his government would travel to Mizoram’s capital on August 5th and discuss the matter with the state government there.

“I’m in constant touch with Mizoram and the Central Government to resolve the crisis. We have undertaken a series of confidence-building measures. Mizoram has already withdrawn cases against our officials and we have reciprocated by withdrawing cases against theirs. I am sending two of my senior ministers to Aizawl on August 5th and they will be received by the Mizoram home minister at the Aizawl airport. This meeting is expected to bring some interim resolution,” Sarma told Open.

The same sentiment was expressed by Mizoram’s chief minister Zoramthanga who told Open: “The de-escalation process is already starting. On August 5th representatives from the Assam government will come to Mizoram and meet representatives from the Mizoram side. I am sure of a conducive atmosphere for settling the border issue. We are hopeful that better days will follow, and that all states of the Northeast will be united.”

Assam relies on a 1933 interpretation of the boundary between the two states that demarcated Cachar district from the Lushai hills district, later known as the Mizo Hills District. Mizoram is unwilling to accept this interpretation as it favours Assam’s claim line in the area

These emollient statements are a big departure from the events of July 26th. The chain of events that led to the crisis unfolded with Assam protesting about Mizoram clearing a patch of inner line reserve forest—to construct a road—in the Lailapur area of Cachar district, in territory that Assam claims belongs to it. Mizoram, too, claims the land. Soon afterwards, the deadly clash between the two police forces took place near Vairengte which lies in Mizoram’s Kolasib district. The Mizoram government accused Assam of sending armed police into its territory and destroying a police picket. Scores of individuals were injured in addition to the death of five Assam policemen and another person from Mizoram.

Since then, even after carefully constructed statements and efforts at restoring peace, the area remains tense. On the Assam side, scores of trucks carrying supplies to Mizoram have been stuck for days. Mizoram describes this as an “economic blockade” while the reality is more complex: locals are involved in the conflict and truckers, too, are hesitant to move as they fear violence.

While the violence surprised many in the country, it has a considerably longer history of sporadic protests and escalating tensions. For example, the same area witnessed violence last October and even earlier.

“It keeps repeating because both sides have a contestation about the actual border. While in 1972 when the Lushai hills became a Union territory after being ceded by Assam and further in 1987 when it became a state that was named Mizoram, the border issue wasn’t ever one that would stop the delineation of borders. But now, if an attempt is made to redefine the border it may not cut much ice,” says Subimal Bhattacharjee, a defence and cyber security analyst from Assam.

Bhattacharjee says that while the battle was being fought on the ground, a large propaganda war was continuing on social media where Twitter hashtags were generated by the Mizoram side. But with the intervention of Union Home Minister Amit Shah and the two chief ministers, several crucial steps were taken, such as the withdrawal of the FIRs and the removal of forces from the flash points along the border. With this, the social media posts also became reconciliatory.

In January this year, Shah, while chairing the meeting of the North Eastern Council (NEC), which has representation of chief ministers of all eight northeastern states, had referred to the tussle. He had asked all chief ministers to resolve their border disputes with the help of technology, such as satellite imagery, which is available with the North Eastern Space Application Centre (NESAC) near Shillong. On July 24th, again chairing a meeting of the NEC, he reiterated this. Prior to that, on July 9th, the Union home secretary had convened a meeting with chief secretaries and directors general of police (DGPs) of both states to work out a roadmap for status quo and agree upon a resolution. “Student groups need to be made to understand the sensitivity of the issue so governments at the helm can resolve it,” says Bhattacharjee.

N THE SECOND HALF of the 19th century, Mizoram—then known as the Lushai Hills district of Assam—was a relatively unexplored area and except for a few intrepid colonial officers not many people ventured there. That did not prevent the occasional raid by the Lushai tribes living there into the plains of Assam, especially in the Cachar district.

In 1871, members of these tribes raided several tea gardens in the area and, in Alexanderpur, a planter was killed. The story is told in the District Gazetteer of Assam. In retaliation, the British sent a number of punitive expeditions into the Lushai Hills from Cachar and Chittagong. This led to a halt of these raids for many years. Even as these military expeditions and political moves were going on, the colonial government issued the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation in 1873, a device meant to demarcate the plain, ‘settled’ areas of various parts of Assam from the hill districts. The “inner line permit” system strictly regulated the flow of men and material between the settled areas and the largely tribal hill districts. In 1875, the inner line permit system was extended to the Lushai Hills district, demarcating it from the Cachar district. Since then, Mizoram—which became a Union territory in 1972 and a state in 1987—has resisted the removal of the inner line permit system. This has become an article of faith in Mizoram.

The de-escalation process is already starting. I am sure of a conducive atmosphere for settling the border issue. We are hopeful that better days will follow, and that all states of the Northeast will be united, says Zoramthanga, chief minister of Mizoram

On July 19th, 1994, then Union Home Minister SB Chavan, while addressing a meeting of chief ministers of the northeastern states, proposed the abolition of the inner line permit system as it held back the economic development of these states. A month later, on August 26th, 1994, during a one-day emergency session of the Mizoram Assembly, a resolution in favour of the inner line permit system was passed unanimously. It said: “The continuance of the ILR in Mizoram is imperative not only for safeguarding the interests of the people and for maintenance of peace and tranquillity, but also strengthening national integration, resolve that the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation, 1873 should continue to remain in force in Mizoram.”

There is one asymmetric feature of these inner lines, wherever they are prevalent—while they restrict the movement of people from other places into these territories, there is no restriction on the movement of people from these ‘protected’ territories outside. In the case of Mizoram, there has been constant pressure for plain land as the state is almost entirely hilly. The way Mizoram interprets the 1875 regulation enables it to claim a part of the forest land on the border with Assam in Cachar district. This is one patch of land that Mizoram claims but which falls in Assam. Similarly, another boundary area—between Karimganj district in Assam and Mamit district in Mizoram—is contested.

In contrast, Assam relies on a 1933 interpretation of the boundary between the two states that demarcated Cachar district from the Lushai Hills district, later known as the Mizo Hills district. Mizoram is unwilling to accept this interpretation as it favours Assam’s claim line in the area.

For a permanent resolution, Assam has also moved the Supreme Court. All the states have reposed faith in the judiciary. The negotiations with Mizoram will continue and the Centre is in the loop, says Himanta Biswa Sarma, chief minister of Assam

This is, however, a narrow legal perspective that gives only a partial picture of what is going on. The reality is that Assam has ‘disputes’ with practically all its neighbours over land. Within Assam, too, land is a prized resource as the state’s land-to-man ratio has steadily deteriorated over the past century. A host of factors like illegal migration from Bangladesh, erosion due to changes in riverine systems and, finally, disputes with other states has made land disputes very volatile politically. For example, Assam has seen violence with Nagaland over a disputed patch on the boundary between Jorhat and Mokokchung districts. This led to violence in 1979, 1985, 2007 and 2014. Finally, the two states agreed to resolve the matter in an agreement signed on July 31st. As a result, police pickets on both sides were withdrawn and the situation has de-escalated.

It is interesting to note the differences between disputes in this region and other parts of India. Recently, in a reply to a question raised in Rajya Sabha, it was said that many other states have boundary disputes with their neighbours. To cite some examples, Himachal Pradesh and the Union territory of Ladakh have such issues. Similarly, Karnataka and Andhra Pradesh have a contested boundary in the Bellary and Anantapur districts, respectively, of the two states. But unlike Assam and Mizoram, this issue is being resolved by asking the Survey of India to demarcate the boundary after the Supreme Court asked it to arbitrate between the two states in 2018. In none of these and other disputes has there been violence of the kind seen in the Northeast. Land, while remaining an important resource, has not been contested violently. In the Northeast, the shrinking availability of land drags everyone, from individuals to governments into such disputes.

The problem is most acute in Assam where no effort has been made in the past to resolve these issues. A culture of keeping things in status quo has been the norm for a long time. Any attempt to change it in favour of the state is either dubbed as an example of Assamese chauvinism or is met with violence. This cul-de-sac of sorts has added to political volatility.

“For a permanent resolution, Assam has also moved the Supreme Court, which is taking the matter seriously. In the interim, all the states—Assam, Arunachal Pradesh, Mizoram, and Nagaland—are maintaining status quo and have reposed faith in the judiciary. The negotiations with Mizoram will continue and the Centre is in the loop. The Aizawl meeting of the ministers is expected to bring some resolution. Assam is only defending its constitutional boundaries,” says Sarma.

In the 19th century, Mizoram—then the Lushai Hills district of Assam—was an unexplored area. That did not prevent the occasional raid by the Lushai tribes into the plains of Assam

It is interesting to note that disputes over shared resources like water have established institutional resolution mechanisms; there is no such apparatus for inter-state land disputes. The effects are for everyone to see. Water disputes rarely turn violent as contesting state governments present their cases in courts and before water dispute tribunals. In contrast, land disputes quickly turn violent and even more so in the Northeast where the resource has immense value and its availability is shrinking.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

Op Sindoor 'new normal' against terror, will watch Pak actions: Modi Rajeev Deshpande

Life After Kohli, Rohit Lhendup G Bhutia

Bulls Stomp the Market on Calls for Ceasefire, US-China Trade Negotiations Moinak Mitra