A Matter of Marcos

WHEN THE PEOPLE Power Revolution entered the Malacañang palace in Manila in February 1986 and uncovered the material evidence of decadent opulence, one image went viral across the world long before the days of social media. Imelda Marcos' 3,000 pairs of designer shoes. There were also regal portraits of a family that had built its own myths, gold-plated Jacuzzis, mink coats, couture gowns, and so on. 'Decadence', or opulence, is not a crime in itself. But in an extremely poor country, the "conjugal dictatorship" of Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos had bought its goodies and stuffed its offshore accounts with money stolen from the people (the Central Bank of the Philippines)—to the tune of almost $10 billion. The deposed first lady bequeathed an adjective to the apocryphal lexicon: Imeldific. She and her long-deceased husband are in the Guinness World Records for the biggest heist at the expense of a government.

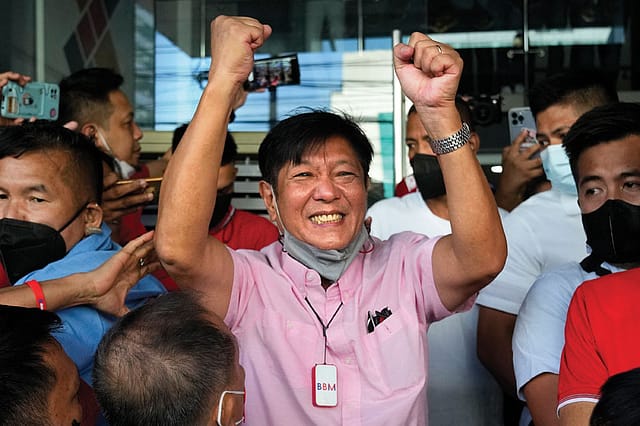

The second child and only son of Ferdinand Sr and Imelda, Ferdinand Romualdez Marcos Jr, or "Bongbong" Marcos, or BBM, has now been elected president of the Philippines in a landslide—almost exactly 50 years since his father had declared martial law in 1972—that brings the family, the country and the saga of one of the most brutal dictatorships on the planet and its long aftermath full circle. Bongbong was brought up to believe the nation was his playground, and he is finally where he always knew he had to be. Except, he did have to work for it. At the time (1980) he took charge as the 23-year-old vice governor of the Marcos stronghold of Ilocos Norte, the family had no inkling that it would be removed from power within six years and forced to flee (to Hawaii).

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

The Marcos family has never apologised. Neither for their kleptocracy nor for all the people who disappeared and/or were killed on their watch.

Ferdinand Sr had pursued a foreign debt-funded infrastructure programme which had quickly turned into a gigantic debt crisis leading to economic collapse. His brutality was epitomised by two events, one well-known and the other a tragic curiosity. Primitivo Mijares, the man who coined the phrase "conjugal dictatorship" in his 1976 book The Conjugal Dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos and Imelda Marcos, disappeared soon after its publication. His school-going son was tortured and dropped from a helicopter, which the police blamed on a fraternity at the University of Philippines. The assassination of Benigno Aquino Jr as he landed in the Philippines in August 1983, on the other hand, would ultimately bring down the Marcos regime.

At the heart of the Bongbong campaign was denial and erasure of what is otherwise a documented past. For all its faults, the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG) brought facts to light, pursued justice for victims, and attempted to make the surviving Marcos family pay. In reality, the campaign goes back more than a decade when the systematic distortion of the country's past had begun on social media. Along with whitewashing the crimes, the 1965-86 period was resold as a "golden era" of prosperity and a crime-free society. The minority that still remembers was hounded, as were veteran journalists and human rights activists. Bongbong avoided the mainstream media and opted out of electoral debates as a matter of strategy.

If Ferdinand Sr created a portfolio of wartime heroics later declared a blatant lie by the US Army, Bongbong continues to claim he graduated from Oxford when records, as well as an official statement by the university, confirm he had failed his exams. It was a repeat performance at Wharton. Moreover, the PCGG produced evidence that his $10,000 monthly allowance, tuition, as well as the estate where he stayed were financed through presidential office funds and secret foreign bank accounts traceable to the family. And his return to the US is problematic since he faces arrest for defying a court order to pay $353 million in restitution to his father's victims. (He also refused to pay taxes on his family estate.)

In the family's own palace in Ilocos Norte, hangs a portrait of Bongbong as a young boy on a white stallion, wearing a golden crown, and holding a Bible and the Philippine flag. Like Imelda's shoes, this painting exists. Perhaps it has brought him to the official presidential palace he had once fled with his family. It remains to be seen what's in store for the Philippines.