The Omens for Liz Truss

The writer, a former Downing Street insider, examines the challenges facing Britain’s new prime minister

Lance Price

Lance Price

Lance Price

Lance Price

|

09 Sep, 2022

|

09 Sep, 2022

/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/LizTruss1.jpg)

Liz Truss outside the Conservative Party headquarters on September 5, 2022 (Photo: AFP)

ON TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 6, after the traditional “kissing of hands” ceremony with Her Majesty the Queen at the Royal Scottish estate of Balmoral, Liz Truss became the United Kingdom’s 56th prime minister, only the third woman in history to hold the post. She had little time for celebrations, however. No previous premier in peacetime has entered the black front door of 10 Downing Street to face such a daunting mountain of challenges.

As if to mirror the political climate at Westminster, central London was in the middle of a thunderstorm as the new prime minister’s motorcade approached. There was a brief pause in the downpour in time for Liz Truss to make her statement in the street, but as she stepped inside the skies darkened once again.

By her own admission, she is not one of the greatest orators in politics. It was a characteristically stiff and unemotional performance, but fitting nonetheless for a new government with a monumental workload and little or no time to enjoy the first taste of power at the highest level.

It would take a man or woman of exceptional ability and determination even to begin to tackle the prime ministerial in-box at a time like this, but after a gruelling leadership campaign that lasted all summer long, the people of Britain have seen little to reassure them that Liz Truss has what it takes. The evidence of the opinion polls is that, however popular Liz Truss may have been among the Tory rank and file, the public more widely have a largely negative view of her.

That may change, of course. Most incoming prime ministers enjoy a political honeymoon of some sort and it’s fair to say that most people don’t have a very clear idea of who she is or what she stands for. That gives her an early opportunity to create a favourable impression if she can, although she doesn’t have much time on her hands. As former US Vice President Walter Mondale said, “Political image is like mixing cement. When it’s wet, you can move it around and shape it, but at some point it hardens and there’s almost nothing you can do to reshape it.” Liz Truss is likely to find it’s quick drying cement in her case, which makes the next few weeks and months critical.

A hundred and seventy thousand mainly elderly and by definition right-wing paid-up members of the conservative party chose the new prime minister. While Liz Truss won the ballot of the membership, her majority was far from overwhelming and she had the support of fewer than half of Tory MPs. So she enters number 10 knowing that she still has to prove herself to her own side, never mind the electorate at large

The UK has now had four prime ministers in the past six years and none to date has been a success. With a general election due in 2024 the Conservative Party has taken an enormous leap of faith that she can buck the trend.

Before considering the task ahead, it is worth reflecting on how and why Truss finds herself in Downing Street at all. It is a sorry saga of party feuding compounded by colossal political misjudgements and personal failings on a scale that has left many international observers looking on in disbelief at a country that was once a by-word for sound, stable government.

For a party that prides itself on its ability to win elections, the Conservatives have not had a truly successful leader since Margaret Thatcher in the 1980s and early 1990s. Since she was forced out by her own cabinet over 30 years ago, three of her successors never made it to Number 10 at all and of those who did, each and every one left office in ignominy. Little wonder then that Liz Truss has very deliberately modelled her image on Thatcher’s. Her critics—and there are many inside her party as well as outside—believe she’s little more than a pale copy, a tribute act who may sing the same tunes but has none of the skills of the original performer.

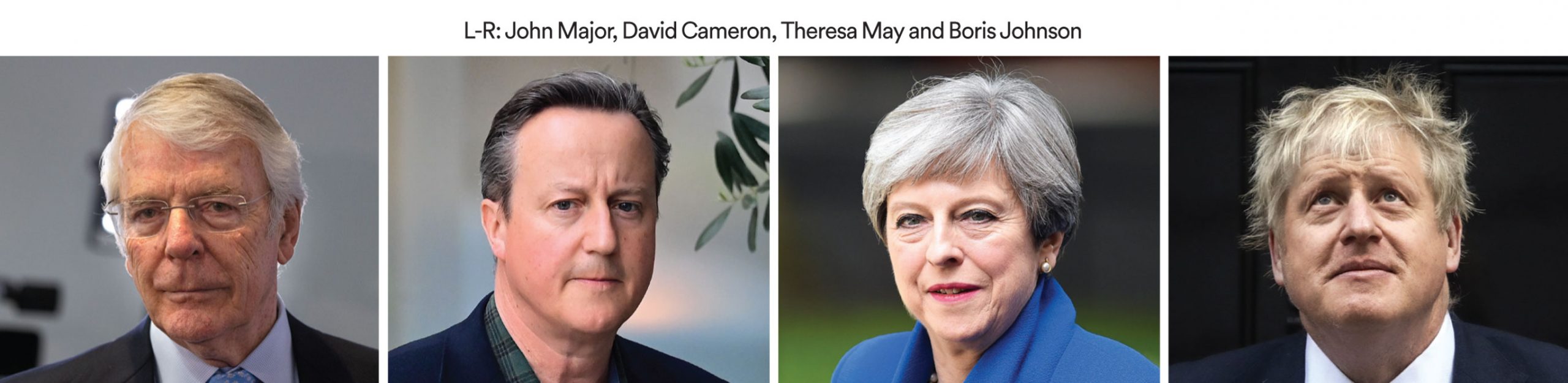

John Major, Thatcher’s immediate successor, led the party to its worst defeat in history at the hands of Tony Blair after the Conservatives’ reputation for economic competence was shredded by the turmoil of so-called “Black Wednesday” in 1992. After 13 years of Labour governments, David Cameron took office as the fresh face of a supposedly modernised party. He took a massive gamble, hoping to end the Tory civil war over Europe with the Brexit referendum in 2016. He lost and resigned in defeat the next day.

Theresa May took over only to have a torrid time as prime minister during which she squandered the party’s majority, failed to get her MPs to unite behind her, and was then unceremoniously booted out by them with little to show for her premiership. Boris Johnson was supposed to be the man to put an end to all the in-fighting, promising to “Get Brexit Done” and winning a handsome parliamentary majority less than three years ago. But now he, too, is gone.

Liz Truss has very deliberately modelled her image on Margaret Thatcher’s. In her attempts to emulate Thatcher, Truss presents herself as a conviction politician. But her critics believe she’s little more than a pale copy, a tribute act who may sing the same tunes but has none of the skills of the original performer

Earlier this year, I argued in the pages of Open (‘The Party Is Over’, January 31, 2022), that Boris Johnson was wholly unfit to be prime minister. I said then that, “he has besmirched the office he holds and in the process has done untold damage to the reputation of politics and British democracy more widely”. A few months later, a majority of his MPs came to the same conclusion and he was out, his dream of a decade in power shattered.

The joke at Westminster was that Boris Johnson was the third prime minister to be brought down by Boris Johnson. He was the leading figure in the Brexit campaign that ended David Cameron’s premiership; he fatally undermined Theresa May from within her own government; and he has nobody to blame for his own political demise but himself.

There are those who think Liz Truss could even be the fourth. Johnson has never believed the normal rules of politics apply to him. If she proves herself unable to meet the challenges she now faces, it is not inconceivable that, like Donald Trump whom he’s been likened to in ways that do no credit to either man, he might try to make a comeback. His own speech outside Number 10 as he left to tender his resignation was, equally characteristically, full of vigour, hyperbole and enigmatic metaphor. He likened himself both to a booster rocket that had served its purpose, and then in the same breath to “Cincinnatus returning to my plough.” That sent less classically trained observers scurrying for their reference books to discover that while the Roman statesman did indeed retire to his farm, he later returned to power and became a dictator.

On the face of it, the threat of a Boris Johnson political resurrection ought to be the least of Liz Truss’ worries right now, were it not for the fact that the political circumstances she finds herself in are so volatile that what should be a ludicrous idea is given credibility by people not normally given to idle fantasy.

THE TORY PSYCHO-DRAMA that has done so much to damage the party’s reputation—and tragically also that of the country itself—has not been ended by the election of Liz Truss. Far from it. The deep divisions in Conservative ranks were exposed for all to see as she and her rival, former Chancellor of the Exchequer Rishi Sunak, battled it out over the summer.

A year ago, Sunak looked a shoo-in for the top job should a vacancy occur. His handling of the economy during the Covid pandemic, his easy-going manner and his excellent communication skills earned him both kudos at Westminster and popularity out in the country. He was the alternative leader that the opposition Labour Party feared most. But the shine quickly came off his reputation when details emerged of his financial and tax affairs, or more particularly those of his vastly wealthy wife, Akshata Murthy, heir to the fortune of her father, NR Narayana Murthy, the founder of Infosys.

John Major led the party to its worst defeat in history at the hands of Tony Blair. After 13 years of Labour governments, David Cameron hoped to end the Tory civil war with the Brexit referendum in 2016. He lost and resigned. Theresa May was unceremoniously booted out by her own MPs with little to show for her premiership. Boris Johnson was supposed to be the man to put an end to all the in-fighting. But now he, too, is gone

If things had gone differently for Sunak, Britain could today have its first Hindu prime minister, and the first with parents of Indian descent. There are many reasons why that didn’t happen and racism, or at least the belief shared even by some socially liberal Conservatives that Britain isn’t ready for a prime minister with brown skin, is undoubtedly one of them. It is not, however, the main one. After all, today for the first time in history not one of the four great offices of state—prime minister, foreign secretary, home secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer—is held by a white male.

No, the main reason Sunak failed to seize the crown is that he was seen to have contributed to the downfall of Boris Johnson by resigning in disgust at Johnson’s latest resort to untruths in the face of a scandal engulfing his government. The electorate that chose Liz Truss over him was tiny and wholly unrepresentative of the country as a whole. A hundred and seventy thousand mainly elderly and by definition right-wing paid-up members of the Conservative Party chose our new prime minister while the rest of us were mere spectators. And many of that select group were, and are, still fiercely loyal to Johnson.

Liz Truss to them was merely the least worst option. They have no great affection for her. And while she won the ballot of the membership, her majority was far from overwhelming and she had the support of fewer than half of Tory MPs. So she enters Number 10 knowing that she still has to prove herself to her own side, never mind the electorate at large.

She will have little time to worry too much about party management though. Management of the economy and tackling high inflation, rising interest rates and a soaring cost of living crisis are much more pressing problems. Vladimir Putin’s war in Ukraine and the knock-on effect on energy prices are undoubtedly factors that have led to the economic tsunami that threatens to engulf her, as is the financial bill left behind by the pandemic, but almost every other leading Western economy is coping significantly better than Britain’s. The UK has underlying problems, many attributable to Brexit, that are a result of decisions taken by the governments of which she was a member. The public are growing tired of attempts to shift the blame elsewhere.

Liz Truss says she wants to break with financial orthodoxy and has been highly critical of what she regards as unimaginative thinking and obstructive behaviour by the Treasury which, of course, was until recently headed by Rishi Sunak. She is pinning her hopes on tax cuts leading to economic growth on a scale Britain hasn’t seen for decades. At the same time she is offering to hold down everyone’s energy bills, despite the massive increase in government borrowing that will entail. It is, to put it mildly, a high-risk strategy.

If things had gone differently for Sunak, Britain could today have its first Hindu prime minister, and the first with parents of Indian descent. There are many reasons why that didn’t happen and racism is one of them. But it is not the main one. Today for the first time in history not one of the four great offices of state is held by a White male

In her attempts to emulate Margaret Thatcher, Liz Truss presents herself as a conviction politician. You can just imagine her echoing Thatcher’s famous dictum that “the lady’s not for turning”. Except, she has already turned, and more than once. She used to be a vocal member of the centre-left Liberal

Democrats, before turning to the Conservatives. She voted against Brexit but is now an enthusiast. As a student, she once publicly called for the abolition of the monarchy, before becoming an arch royalist. That no doubt made her meeting with Her Majesty at Balmoral more comfortable, but it does raise questions about what the real Liz Truss believes, if anything.

All of this gives her critics, including the opposition Labour Party which is currently ahead in the polls, plenty of ammunition with which to attack her. But they need to be careful. She may be a political shape-shifter, but her career path shows she is willing to do and say whatever it takes to get ahead and succeed.

Thatcher insisted “There Is No Alternative” when administering unpopular medicine to the British economy. Liz Truss can make no such claim. A large part of her own party believes there is a better way to handle the crisis, and she faces opposition parties in parliament that have worked hard to regain the trust of the public and offer a competent, pragmatic alternative government if she fails.

At three years and 44 days, Boris Johnson had one of the shorter premierships in British history. For all her outward confidence, Liz Truss must know that the next few weeks will be crucial in determining whether or not she will find her name even lower down that league table when the next election comes.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

India hammers Pak air bases at Rafiqui, Murid, Chaklala, and Rahim Yar Khan in a show of unflinching force Open

How India (re)built its defence preparedness and war readiness V Shoba

Cracks in the Pink Fortress Open