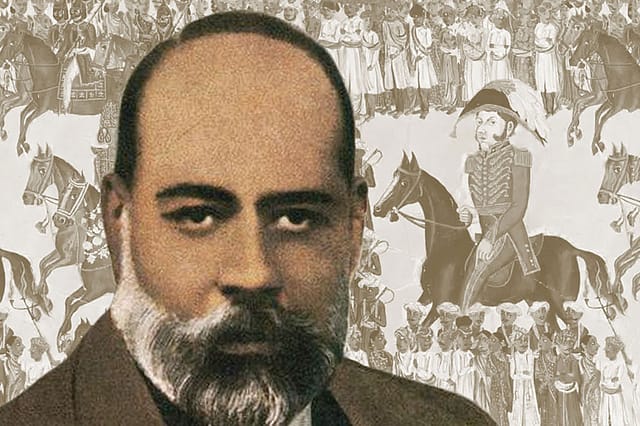

Syed Mahmood: Justice Courage

COLONIALISM SPLIT THE personality of the subjugated. The demands of survival under an alien power could rarely synchronise with the pervasive emotions of an indigenous culture and, more substantively, with traditional concepts of social, criminal, and economic justice ingrained on the mindset over countless generations. A pre-colonial polity like feudalism neither promised nor offered equality, but prince and serf shared the same ethos, language and culture. The class divide was a different story from racism.

The British took pride in white supremacy and found evidence for it not merely on the battlefield but in every aspect of their relationship with the conquered people, from administration to justice to intellect and knowledge. They might, in moments of generosity, stoop to improve the ways of native barbarians, or throw a few crumbs from the bloated larder of Western science. They flaunted racism in the first phase of their rule, and barely disguised it in the second. They had no desire to identify with 'inferior' Indians. They inherited an economy from Mughal and other Indian rulers in which India had nearly 25 per cent of world manufacturing output and left India with less than 2 per cent; in the process they transferred wealth from India to Britain with remorseless insistence as nothing more than the legitimate due of a superior race that was bringing "civilization" to a dark and heathen world.

We get a clue of the thinking Indian's response in the subtitle of this well-researched, fluent, and balanced biography of the first Indian judge of the Allahabad High Court, Syed Mahmood: "Colonial India's Dissenting Judge" (Syed Mahmood: Colonial India's Dissenting Judge, Bloomsbury, 274 pages,

₹ 699).

Syed Mahmood would have been a brilliant, and perhaps even singular, judge in any age but he might not have resigned under what the authors Mohammad Nasir and Samreen Ahmed describe as "acrimonious" circumstances in 1893, after a five-year tenure in the high court, in any previous dispensation. He had been a "temporary" judge four times before that, since 1882. His legal reputation, already established at the district level in the United Provinces, was phenomenal, and he seemed destined for greater honours than any Indian of his era in the judiciary. Sir Whitley Stokes, law member of the Council (equivalent to a contemporary law minister) between 1877 and 1882, noted in his book The Anglo Indian Codes: "No judgments in the whole series of Indian Law Reports are more weighty and illuminating than those of Justice Syed Mahmood". His legal virtuosity, his advocacy of human rights, his sympathy for the litigant, his commitment to the principles of natural justice—"hear the other side" and "where there is a right, there is a remedy"—won the admiration of even those who might have preferred a contrary decision. Success brought its usual rewards. The palatial Swaraj Bhavan, birthplace of Jawaharlal Nehru and home of Motilal Nehru, was once the residence of Syed Mahmood.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

He was less accommodating towards authority than his eminent father, Sir Syed Ahmad Khan. The father was practical, as required of an achiever; the son a liberal who lived in the penumbra of assertion and cooperation, like his friends Tej Bahadur Sapru and Ananda Mohan Bose. As his legal colleague Satish Chandra Banerji wrote in Hindustan Review, Mahmood wanted Indian progress, sympathised with the ideals of the incipient Indian National Congress, was committed to fellowship between Hindus and Muslims, and had absolutely no patience with servility. "Having differences in religion does not eradicate the entire influence of those matters in which Muslims and Hindus work together," he said at a dinner hosted in his honour upon his return from London as a barrister. "Those who know me well, also know that my training and upbringing was done in such a manner and in such an atmosphere that I value national unity [hum watani] and its enthusiasm and ideas above all other ideas of humanity." It is notable, and even remarkable, that this was the first dinner in the province at which Muslims, Hindus and the English sat down together.

Mahmood lived at a time when, broken by the comprehensive military failure of the Indian uprising in 1857, the Muslim intelligentsia had began a serious reappraisal of the causes and consequences of the long decline and fall of the Mughals, once rulers of a preeminent world power.

He attributed the fall of the Mughal empire directly to the destructive intolerance of Aurangzeb, describing him as "the degrader of his ancestral heritage, the degrader of race and religion" who eventually succumbed "to the curses of the suffering devotee, to the united force of exasperated millions". Implicit in this anger is the lingering nostalgia for what might have been had Shah Jahan's official heir Dara Shikoh, a philosopher-prince and an advocate of religious and social harmony, succeeded on the battlefield against his younger brother Aurangzeb.

Mahmood's father, Sir Syed, spurned the temptations of sentimentality in his analysis of Indian feudal decay. Sir Syed rejected the view, popular among the Deoband clergy, that an unremitting jihad against the British was the way forward, and sought answers in the acquisition of modern education, sourced in the West, but without abandoning the traditional study of Sanskrit, Arabic and Persian. The result was the establishment of the Mohammedan Anglo-Oriental College at Aligarh in 1877, the first incarnation of a great institution, the Aligarh Muslim University (AMU). The foundation stone was laid by the Viceroy, Robert Lytton Bulwer-Lytton; Henry George Impey Siddons was appointed the first principal. Its curriculum included English, Arabic, Sanskrit, Latin, Greek, and options such as music and traditional medicine. By 1890 it was offering a law course. By 1920 it was a university.

The biographers, Mohammad Nasir and Samreen Ahmed, do well to quote Mahmood's passionate speech at the foundation ceremony, describing it as the first time "in the history of the Mohammedans of India that a college" owed "its establishment not to the charity or love of learning of an individual, not to the splendid patronage of a monarch, but to the combined wishes and united efforts of the community. It has its origins in the causes which the history of this country has never witnessed before. It is based upon the principles of tolerance and progress such as find no parallel in the annals of the East…." This was the difference. The era of sovereigns and patrons was over. The community had to find its feet, and then walk towards modernity. The journey began in Aligarh; but too many Indian Muslims became confused about the route and lost their way in the middle of the 20th century.

UNFORTUNATELY, SYED MAHMOOD himself lost his senses at the peak of his abilities and potential influence. We do not know the reasons for his alcoholism, and what the authors describe as "consequent sensory disturbances". This biography, excellent in so many respects, does not elaborate. By 1897, when Mahmood returned to the Aligarh campus, he had become a drunken embarrassment, unable to live in the same home as his upright father. Sir Syed either left the home they shared, or was turned out by the son; narratives differ. In any case, the grand old man died heartbroken on March 28, 1898. Mahmood's conduct as secretary of the college after his father's death became so wayward and reprehensible that Theodore Beck, the principal, wrote to Mohsin-ul-Mulk, a trustee, that the authorities would have to choose between the two, "for my health won't stand acting as a jailor of a lunatic asylum". As it happened, Beck did pass away in 1899, and Mahmood was eventually farmed out to a relative's home in Sitapur.

Mahmood's marriage collapsed. His wife Musharraf Jahan Begum sought separation and then asked the government to appoint the college's famous principal, Theodore Morrison, guardian of their young son Ross Masood. The breaking point seems to have been Mahmood's insistence that Ross plough the fields on cold nights to understand agriculture and eat raw meat to become a "lion cub". Perhaps this is what constitutes "sensory disturbances", but one cannot be sure. Morrison did take responsibility for Ross's studies after Mahmood's death in 1903. Ross graduated from Oxford with a second in history (Mahmood was a Cambridge man), joined Lincoln's Inn, returned to India to set up a law practice in Patna, became vice chancellor of AMU in 1929, was knighted in 1933 and became a founder of Osmania University. In 1924, EM Forster dedicated A Passage to India to Ross Masood.

Whatever his later personal lapses, Mahmood's place in history is cemented by his seminal, eloquent and independent interpretation of the law, and his exemplary courage in defying Chief Justice Sir John Edge. Given the fact that this biography is written by two lawyers, it is unsurprising that the best section deals with Mahmood's career as a judge, beginning with his appointment on August 1, 1879 as sessions judge at Rae Bareli.

It is pertinent to repeat that Mahmood was not hostile to British rule; he believed in what he called "liberal imperialism". But "liberal" was more important than "imperialism", and it included the Indian's fundamental right to tradition. Thus, Mahmood overruled a British civil servant's decision to ban the morning drumbeat, or naubat, because it disturbed his sleep and then, one morning, went out to play the drum himself. The alarm surely began to sound in the confines of British rule as they heard the tintinnabulation of an eccentricity gene.

Mahmood's 46-page judgment in Deputy Commissioner Rae Bareli vs Lal Rampal Singh, eventually upheld by the Privy Council, now preserved in the museum of the Allahabad High Court, was considered so brilliant that the Privy Council told the Indian government that such a talent should not be wasted on subordinate judiciary, leading to Mahmood's elevation to the Allahabad High Court. His dramatic career is best studied in the book, but suffice to sum up his resignation was his explanation that he had not become a high court judge in order to whimper before the "frowns and smiles" of Sir John Edge, when Sir John thought that the frown at intemperance outweighed the smiles at acumen.

Biography as a skill has many inlaid traps, not least of them being hagiography and inaccuracy. This book is above such weaknesses. Mohammad Nasir and Samreen Ahmed have made a brilliant start to a parallel career in writing. It will, alas, never be as lucrative as the law, but its collateral benefits are invaluable.