NTR: He Dared to Play God In Politics—and Won

AS BASTIONS GO, Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka seemed rock-solid for Congress, voting for the party even in 1977 when it lost nearly every seat from Punjab to Bengal. Andhra Pradesh sidestepped the trauma of Emergency and endorsed Indira Gandhi in a counter-sweep. She repeated this adulatory victory in 1980. A Congress defeat in Andhra was incomprehensible to the political calculus. Indira Gandhi was a demi-goddess to voters.

Given human nature and its excesses in politics, it was perhaps understandable, if not quite forgivable, that Congress leaders turned smug, complacent and sycophantic. The rot in Andhra was evident in an incident which became embedded in public consciousness. The seventh chief minister of the state, Tanguturi Anjaiah, was neither naïve nor a simpleton. Anointed in October 1980, he merely behaved as one who had won an unexpected lottery in the Congress stakes and recognised that his survival lay in sycophancy. Hyper success breeds hyper stupidity. And so, when Indira Gandhi's son Rajiv, then general secretary of the party, came on a private visit to Hyderabad in 1982, Anjaiah organised a maharaja's welcome at Begumpet airport. The entire cabinet was lined up at the airport to pay homage, while performers put on a show of drums and dancers at a cost of Rs 25 lakh, a very substantial sum in that era. Rajiv Gandhi was aghast at the display on the tarmac, which also happened to be a violation of civil aviation rules. He complained to his mother. A tearful Anjaiah never understood why he had been sacked for behaviour that had become endemic to Congress culture.

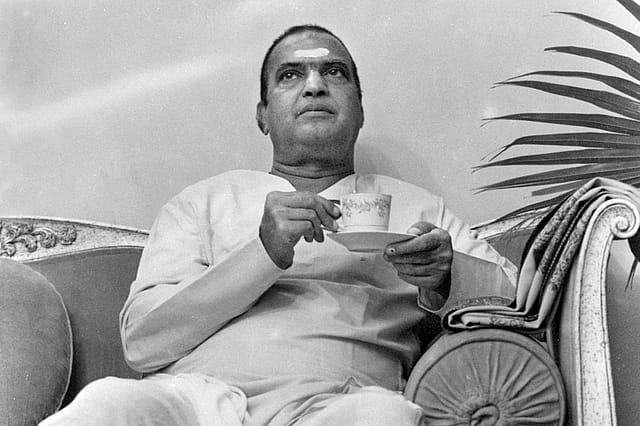

One man, then still on the fringe of the political space, understood what had happened: Telugu self-respect had been violated. His name

was Nandamuri Taraka Rama Rao. Popularly called NTR, he was a cinema superstar with a fan base of millions built across a career spanning nearly 300 films over three decades in which his portrayals of Lords Krishna, Shiva and Rama had burnished his image with a halo.

The Congress establishment did not take NTR seriously when he launched Telugu Desam in 1982, dismissing him as an elderly novice, an eccentric has-been with notions far above his screen status. Observers scoffed at the 'upstart'. Every conventional argument was dusted out of a lazy cupboard to reinforce the assumption that Congress would once again win in the Assembly elections scheduled for 1983.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

What the politico-media complex could not fathom, largely because it rarely left the air-conditioned cabins of the capital, was that facts were changing where it mattered, on the ground. There was one media magnate, however, who knew that the moment had found a leader. Ramoji Rao, creator of the Eenadu group, an innovative genius who should rightly be described as the NTR of media, became a mentor.

NTR was 59 when he decided that he would change the destiny of his people. His opportunity lay in the 1983 elections. By any norm, there was simply too little time to convert an idea into a mass movement. Telugu Desam had not yet been formally recognised by the Election Commission, and so NTR's candidates would have to contest the polls technically as independents.

The hurdles that NTR overcame are evidence of his formidable charisma. There was uncertainty about whether his candidates would be able to fight on a common symbol, for his was a new party. Fortunately, in the 1977 General Election, the Election Commission had allotted a common symbol to the Janata Party although it had not been officially formed. Precedence established, NTR got the bicycle as party symbol. But it was still an infant image pitted against a Congress brand reinforced by Indira Gandhi's phenomenal name recognition.

History is made by those who take command of the chariot and are driven by a vision of the future that leaps beyond the imagination of the present. NTR's lonely jeep on the campaign trail grew into a caravan, and the caravan bloomed into an endless procession that demolished the shibboleths of accepted wisdom.

I had the privilege of travelling with NTR on this campaign. His unique style of sitting on a rug atop a Chaitanya Ratham would make the front pages, but that was yet to come. We were in a jeep with canvas as roof and sides, driving through the pale dust of rural roads and the uneven, blotchy tar of rudimentary highways. Early days, but one could already see a lustre in the eyes of villagers and residents of small, lost towns. There was sudden hope in the air as an electoral metamorphosis began to catch the magic of change. One seemingly small but significant incident, a metaphor of NTR's basic ideology, is etched in my memory. As the miles rolled by, NTR suddenly pointed to a milestone. The numerals were in English. When I become chief minister, he said without ceremony, in a very matter-of-fact manner, the numbers will be in Telugu. What was the point of a milestone if it did not serve the poor?

No one had thought of it since no one looked at problems from the perspective of the ground. Even sincere ministers dictated remedies from patrician heights. By the 1970s, the ministerial focus had degenerated to a point where decisions were measured largely by the money you could make. Self-interest rose over public interest. NTR changed the dynamics of decision-making. He sought solutions from the lived experience of the impoverished.

Indian democracy is kept robust by voters, not victors. NTR won a huge majority in his first election, taking 201 of the 294 seats in the state and becoming chief minister on January 9, 1983. Congress was stunned into torpor. An elephant takes a while to lose weight but can lose its élan after a single defeat. NTR destroyed the myth of Congress invincibility in Andhra and created new space for regional forces.

Unable or unwilling to admit its failings, Congress fell back on a shortcut explanation: it had been defeated by a cinematic chimera that would fade with sunrise. Of course, NTR was a screen legend. But every legend does not add a political chapter to its saga. NTR's transformational genius lay in his abiding commitment to the poor. That came from his heart, not from a script. The quality of NTR's governance eroded any facile analysis. The one thing he brought from his cinema skills was a slightly rotund oratory that enthralled voters. A palpable thrill energised the audience whenever he rose to speak.

I had personal experience of his acting skills. During his second term as chief minister he gave me time for a television interview. Five, said his secretary on the telephone. Then came a startling clarification: 5AM. An early riser, he was ready by the time we reached his home around 4.30. A whimsical thought occurred to me. It would make for good television if we could film the superstar getting up from bed for such an early interview. He was nonchalant. He went back to his floor mattress, and calmly simulated a classic 'wake-up' shot for our cameras, not forgetting to flick his fingers after a yawn. When the interview was over, NTR courteously invited me to join him for breakfast. It was some breakfast. A whole-chicken meal was served. He lived large.

He governed with a large heart too. There were subsidies to those below the poverty line for basics: bread, cloth, shelter. He introduced mid-day meals for schoolchildren. An article should not become a catalogue, so there is no need for a read-out of his welfare schemes. Suffice to mention that concern for the forgotten was the basis of his triumph.

Paradoxically, NTR's one political weakness lay in his moral strength. He neither understood nor practised deceit. But deceit was considered clever politics by Congress. On August 15, 1984, while NTR was recovering from heart surgery, Delhi played dirty. The governor, Thakur Ram Lal, arbitrarily dismissed his government and placed a defector-puppet in power. The conspiracy assumed that NTR's MLAs would follow the smell of office, however acrid it might be, if fuelled by bribes.

Congress had underestimated the roar of a wounded lion. There was statewide outrage. Defectors were intimidated by NTR's swelling support, while his friend Rama Krishna Hegde, Karnataka's suave, brilliant leader, gave much-needed sanctuary to his MLAs in a safe-haven hotel in Mysore. NTR chiselled them out of the grip of inducement. When the partisan governor refused to recognise reality, NTR led his famous Chaitanya Ratham protest campaign. Indira Gandhi was forced to dismiss Thakur Ram Lal. NTR was sworn in once again.

Such was the momentum that in the General Election of 1984, which saw a national upsurge of sympathy for Rajiv Gandhi after Indira Gandhi's tragic assassination, NTR won 30 out of 42 parliamentary seats. Telugu Desam became the main opposition party in Delhi. The Left Front withstood the wave in Bengal but every other party was drowned. MG Ramachandran's AIADMK only floundered but went down to 12 seats in Tamil Nadu.

Delhi turned out to be, in the long run, a trap. As NTR's focus was split between state and country, he created a National Front which went on to form a government at the Centre in 1989 with VP Singh as prime minister. The price was paid in Hyderabad. NTR lost the Assembly elections in his state. The laurels would return in 1994, in the signature style of 1983, but India had changed during the five years he was out of power, as had his family equations. He had aged. His heart attack in 1984 was followed by a mild stroke in 1989. On January 18, 1996, at the age of just 72, he passed away after a second heart attack.

Few leaders have been worshipped with such near-divine ardour. NTR merged his screen magnetism with a dramatic public life in a subliminal if not always subtle way. He was not a godlike figure who promised heaven in eternity; he delivered on earth. The Viswa Vikhyatha Nata Sarvabhouma, or World-Famous Thespian Star, became an iconic catalyst of change. In one life NTR played many roles and was a superstar in each one of them.