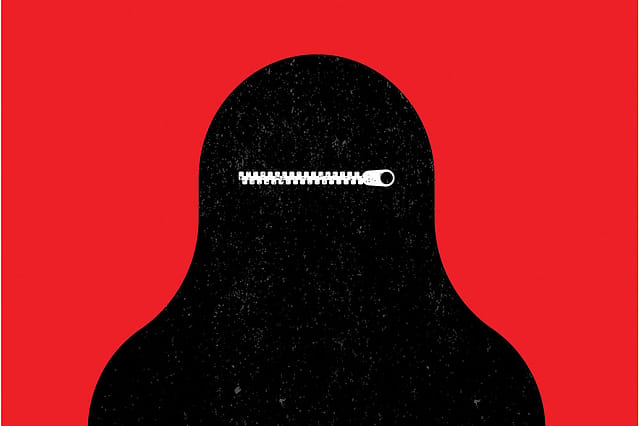

Hijab Row in India: Just Like Us

WOMEN ACROSS SOUTH Asia and beyond have for centuries loosely covered their heads and bosoms, regardless of religion, shielding themselves from unrelated men as well as from the hot sun.

Women entering the workforce in urban areas have been quicker to shed traditional attire. Those who find these changes threatening sometimes find ways to keep women in their place. Religion offers a convenient pretext.

The more conservative Muslim women in South Asia also traditionally wore a burqa, more all-enveloping than a chaddar or dupatta. My grandmother in Allahabad, Uttar Pradesh, used to wear a brown burqa that she discarded eventually in Karachi.

Growing up in Pakistan under the military dictatorship of General Zia-ul-Haq, 1978-88, women like me have firsthand experience of such tactics. We watch in horror as shadows of the Zia dark years seem to spread across the border into India.

"You have turned out to be just like us," wrote the Pakistani poet Fahmida Riaz, addressing Indians after the demolition of the Babri mosque in 1992. "Where were you hiding until now, brother?"

It was this tragic event initiated by the Hindu rightwing that contributed to the Indian Muslims' growing sense of insecurity and allowed radical Muslims to gain ground, and gave rise to identity politics.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

With her political acumen, Fahmida Riaz would have known, of course, that we have always been alike, the protestations of our rightwing constituencies notwithstanding. The killing fields of Punjab and Bengal in 1947 proved this. Mob violence and lynchings in the name of religion over the past years have provided further proof. So does how we treat our poor and vulnerable communities. Does the "hijab row" that started in Karnataka belong in this list? It's a question worth considering.

Coming back to traditional standards of modesty for South Asian women, in cities, it has long been enough for women to wear a dupatta, the long, flimsy piece of cloth that traditionally covers the head and bosom. With modernisation/Westernisation, the dupatta increasingly became a token to complete an outfit, relegated to one shoulder, flung across the neck, or removed altogether.

As an intern at the daily The Star in Karachi, 1981-82, I'd go to work in a salwar kameez, often without a dupatta. Some of the other women journalists wore dupattas, some didn't. The men we worked with, or encountered on our way to work, didn't bother us. It was simply not an issue.

But General Zia's military dictatorship made it into one. Trying to legitimise his rule on the pretext of religion—Pakistan wasn't 'Islamic' enough—General Zia began to clamp down on women's freedom.

The military regime's obsession with overclad women extended to the sham parliament where the general would present women with chaddars—a heavier, larger version of the dupatta.

When women on television were directed to cover their heads, one newscaster resigned. Interestingly, across the border in India, we heard that women newscasters in Amritsar were also asked to cover their heads—it's part of Punjabi culture, they said.

Meanwhile, in Pakistan, the rhetoric of 'chaddar and char-dewari' (purdah and the four walls of the home) began being touted as a prerequisite for women's safety.

I hit back in the only way I knew. I typed out a satirical piece titled 'A hundred and one uses of a chadar', and illustrated it with single-column cartoons.

If you cursed yourself during a journey where you found yourself without napkins to wipe the kids' hands, I wrote, "you are one of the so-called 'liberated and modern' women, uninitiated and chadar-less, who have not yet seen the light." I listed various creative uses for the garment, including "pretend to be a laundry bag" to hide from unwelcome guests or "refuse to let a doctor near you on the grounds that you are too modest."

"Yes indeed, a chadar is one of the most useful and absolutely essential items of a woman's wardrobe. Without it you are nowhere. There are so many uses for it, once you've experienced its dependability and durability, you will never want to be without it."

CAN'T SAY THE same for the "hijab", a tight head covering that originated in the Middle East, and gradually made its way into South Asian culture in the 1980s. This coincided with the export of manpower and labour from the region to the Gulf states as well as the geopolitics in the neighbourhood.

America's entry into Afghanistan via its proxy Pakistan transformed the Afghans' national war of liberation against the Soviets into a 'holy war', a jihad backed by Saudi Arabia seeking to assert its brand of Wahhabi Islam against the Shia Islam making waves through the Iranian Revolution.

The hijab first became visible in south India with its strong connections to the Gulf states, much before it spread to the north. The phenomenon prompted a young journalist from Kerala in 2009 to pitch a piece on the rise of the hijab in her region to the online publication TwoCircles.net. The piece contains interviews of several women and concludes that while the hijab used to be viewed as a sign of oppression, that narrative "failed as more and more educated women are turning to the hijab."

Opposition to the garment is based on fear, she commented. "A fear of what would happen if women get to know and practise Islam well. The fear that traditional leaders have of the loss of their authority. However, women who wear the hijab feel safe, secure and confident. And that helps them to succeed." ('Hijab in Kerala: The transformation from ignorance to knowledge', Najiya O, TwoCircles.net, August 8, 2009.)

It's not just a symbol of religious identity but "also a fashion statement and a way to connect to and be part of a global conversation," comments Boston-based biotech professional Kashif-ul-Huda, Indian-origin founder and former editor of TwoCircles.net.

"It's complicated", as he says. Not all scholars agree that Muslim women must wear the hijab. Some uphold the view that the real purdah lies in the eyes.

In 1993, about 10 years after my little satire on the chaddar, as a features editor with The Frontier Post in Lahore, I commissioned a journalist in the industrial town of Faisalabad (former Lyallpur) to report on the education department's directive to college principals telling female students to cover their heads to and from school. The ministry of religious affairs had jumped in, directing the principals to report back with their compliance.

I wanted to highlight the pressures on young women. If they want to cover their heads, they should be allowed to do so, I reasoned. They don't need a directive from the men at educational or religious ministries telling them what to wear and how to wear it.

The onslaught has continued, with women's clothes and bodies being increasingly politicised.

THE PUSHBACK FROM working women and activists has led to some gains. There are also setbacks. In general, women in Pakistan have increasingly been pushed into "covering" at least in urban public spaces. For rural women, the question doesn't generally arise.

In 2018, women's groups initiated a celebration of women's rights on International Women's Day, March 8, called the "Aurat Azadi (women's freedom) March". Held in cities across the country, it has become an annual event, observed even in small towns and villages. The more popular it gets, the more threatened the orthodox elements of society feel.

In past years, some participants carried placards with slogans that irked those holding conservative, traditional views. These slogans have been used as a pretext to attack the entire event, and to ban it.

The ministry of religious affairs in Pakistan has now urged the government to declare March 8, International Women's Day, as "Hijab Day" in Pakistan. Really?

There is already an annual World Hijab Day, started on the first day of February in 2013 by an American Muslim woman in New York. Which makes sense if you're trying to assert your Muslim identity, particularly, as an immigrant.

Women in Muslim-majority Pakistan hardly need support and solidarity to assert their Muslim identities.

In neighbouring India, it is worth noting that despite the onslaught of Hindutva supremacy, Muslim women have been making strides. They hold top ranks in universities across the country. Besides education, they are steadily advancing on various fronts, including financially, politically and culturally.

Kashif-ul-Huda shares an anecdote from a few years ago, when he visited India and spoke to a largely Muslim college audience in Azamgarh, UP. Towards the end, he asked how many of the female students wanted to go abroad.

All hands went up. Why?

"Ambition. They are all very ambitious."

And that is very threatening not just to the Muslim orthodoxy, but also to the Hindutva lobby. You are just like us, after all, as Fahmida Riaz said. No surprise that vested interests are using the hijab row to advance their own agendas, with competitive communalism further hardening positions.

Many of the protests are clearly orchestrated, with rightwing organisations handing out saffron scarves to students to stage protests, as investigative journalists have revealed. (' TNM Investigation: How Hindutva group mobilised saffron-clad students at Udupi college ', February 9, 2022.)

This is politically convenient for the ruling party as the senior journalist Prem Shankar Jha has outlined in a recent piece: "Like the Pulwama suicide bombing in 2019, the hijab controversy has come as an unsolicited gift to a BJP government that has been on its back feet since its mishandling of the COVID-19 crisis last year. ('Thanks to the Hijab Issue, India is Falling Once More into the Communal Trap', The Wire, February 2022.)

In the end, the issue is not about uniforms and hijabs, but upholding power politics and keeping Muslim women down. Having seen the pattern in Pakistan, it's sad to see it being replicated in India.