Healing a Wounded Civilisation

A Uniform Civil Code is not merely a legislative matter

Sandeep Balakrishna

Sandeep Balakrishna

Sandeep Balakrishna

Sandeep Balakrishna

|

28 Jul, 2023

|

28 Jul, 2023

/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Healing1.jpg)

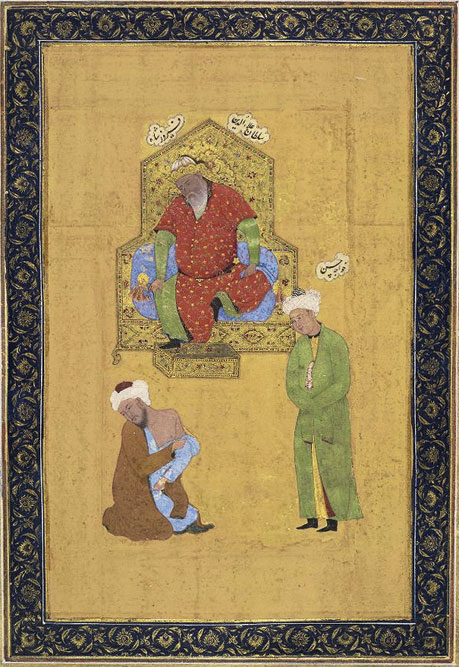

A watercolour painting of Prince Aurangzeb at war, circa 1635, courtesy Royal Collection Trust

THE STORY OF Sidi Maula is intriguing and illustrative. A Sufi dervish hailing from Persia, Sidi Maula became an influential power centre during Jalal-ud-din Khalji’s reign and conspired to assassinate him and usurp the throne. The plot was discovered and Jalal-ud-din had him executed in a gruesome fashion. The whole of the Islamic clergy in his dominion was horrified. It was beyond their wildest imagination that the sultan had actually dared to kill a pious man of Allah. A Sufi at that. However, not one member of his Ulema summoned the courage to even voice his outrage. The clerics consoled themselves by unleashing textual curses against Jalal-ud-din, posthumously.

This 13th-century episode is symptomatic of a central theme in the history of Muslim rule in India. It clearly shows the reality that despite being the guardians and interpreters of the Islamic law, the Ulema’s power was circumscribed by and overridden at the whim of the sultan. Thus, for all its exalted and revered status within the Muslim community, there were practical limits to enforce the Shariat even in an absolute Islamic regime. Arun Shourie in his brilliant A Secular Agenda, summarises this theme quite well:

“In the Mughal period the Shariat had its downs and ups—from Akbar not using it as the rule of decision, from Jehangir whose own conduct…could scarcely be said to be in accordance with the [Shariat], to Aurangzeb’s well-known attempts to enforce it.”

Aurangzeb is perhaps the best example. Although he out-orthodoxed his orthodox Ulema, he ultimately failed to enforce the Sharia. It cost him his empire. But to turn to Shourie again (emphasis added):

“…the life of the people in general continued outside the Shariat…As Mughal rule waned rapidly after Aurangzeb, the Shariat became even more of an abstraction to be merely revered from a distance… The growth of revivalist movements, the fiery exhortations of [its] leaders… Shah Waliullah [et al]., to return to ordering affairs according to the Shariat show…that life and rulership were not organised in accordance with it.” [‘Not’ emphasised in the original text]

In the Mughal period the Shariat had its downs and ups—from Akbar not using it as the rule of decision, from Jehangir whose own conduct could scarcely be said to be in accordance with the Shariat, to Aurangzeb’s well-known attempts to enforce it. Aurangzeb is perhaps the best example. Although he out-orthodoxed his orthodox ulema, he ultimately failed to enforce the Sharia

Barring Aurangzeb’s dogged and fanatical attempts to enforce the Shariat throughout his empire, most sultans had grudgingly chosen pragmatism over force. UC Sarkar’s magnificent work, Epochs in Hindu Legal History, shows how this pragmatism operated in the realm of laws (emphases added):

“The period of the commentaries and the Nibandhas [digests on Hindu Dharmasastras]… covers the longest period from 900 A.D. This period… [is] the… Mahomedan rule in India. Most of the important commentaries and Nibandhas were composed during [this] period. This is a sure indication that Hindu law did not die out during the Mahomedan rule in India. It could not die out. During the Mahomedan period the natural and untrammelled growth of Hindu law was simply arrested to some extent. The rulers were strangers to this country. They did not accept Hindu law for themselves; nor did they abolish the Hindu system of law altogether. Hindu law was allowed to be reserved for the Hindus… so far as its civil aspect was concerned. Thus arose the two separate systems of personal law which practically proceeded on parallel lines and which remained to be modified later only at the time of British administration.”

UC Sarkar’s note about the two parallel legal systems reflects an even more fundamental reality. Till date, the philosophical core of Hindu Dharma has remained uninfluenced by any religion or sect or cult that came into India from outside.

The commentaries and Nibandhas were the responses of Hindu society which was trying to adjust to an oppressive alien regime. The period from 900 CE up to 1858 CE is where we notice the elements of rigidity, stratification and stagnation of Hindu society birthed in these works. Over the centuries, these became the new orthodoxy. Without kingly protection, Hindu society in large parts of India was left to fend for and defend itself as best as it could. It is also tragic that a 10th-century Dharmasastra work like Devala-smriti, which contains concrete procedures for reconversion of Hindus, was largely ignored. An honest and comprehensive study of the Dharmasastra literature composed in this period will be eye-opening to say the least.

The foregoing historical survey also shows that at no point was the Muslim community governed by the Shariat in toto throughout India. The existence of multiple schools of Islamic law—Hanafi, Shia, Ahmadiyya, etc—simply made this impossible and impractical. The debates that preceded the passage of the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937, reveal the kind of sharp differences that existed among these schools even on fundamental topics like marriage, dowry, and inheritance. In fact, several Muslim legislators—Yamin Khan, for example—emphatically declared that “there is no such word [called Shariat] ever used in any [Muslim] law book…”

Neither are these differences restricted to India. In several Islamic countries, the application of the Shariat is neither total nor homogenous throughout the land.

THE DECADAL OPPOSITION to the implementation of the Uniform Civil Code (UCC) rests on the edifice of the aforementioned Act of 1937. But the edifice is actually a myth. Several Muslim legislators had opposed its passage but it was codified thanks to British skulduggery. Which opens up an old chapter of this story.

Through a series of legislation beginning in mid-19th century, the colonial British had reduced the differences that had existed between the personal laws of the Hindu and Muslim communities that had been operating in parallel.

In practical terms, this meant the effective demolition of such portions of the Shariat as were still in operation. In no particular order, these were mainly the Caste Disabilities Act, the Married Women’s Property Act, the Majority Act, the Transfer of Property Act, the Guardians Wards Act, the Indian Contract Act, the Indian Evidence Act, the Criminal Procedure Code, and the Indian Succession Act. The last of these laws, the Child Marriage Restraint Act (the Sarda Act), was passed in 1929. To invoke Arun Shourie yet again (emphases added):

‘What was still called “the Shariat” was by now a thorough amalgam—of what Islamic jurists had held, of elements of Hindu law and local custom, which was invariably the Hindu custom of the locality, and the rulings of… British magistrates and judges. So much so that it went by the name of “Anglo-Mohamedan Law…”’

So, what had changed from 1929 to 1937?

A sufi dervish hailing from Persia, Sidi Maula conspired to assassinate Jalal-ud-din Khalji and usurp the throne. The plot was discovered and Jalal-ud-din had him executed in a gruesome fashion. The whole of the Islamic clergy in his dominion was horrified. It was beyond their wildest imagination that the sultan had actually dared to kill a pious man of Allah

The Government of India Act, 1935, was followed by sweeping Congress victories (the Congress was regarded as a Hindu party). It formed governments everywhere. But to cut a long story short, the nervous British government found it expedient to play the Muslim community against the Hindus. The so-called Shariat Act was just another ploy in this endeavour. Its most regressive provisions were mooted by the fundamentalist elements of the Muslim clergy—these were the same forces that had unleashed the Khilafat havoc and had seeded the Tablighi movement. Minus British blessing, the so-called Shariat Act couldn’t have been a reality. The Muslim clergy got only so much wiggle room that the British granted it. In the earlier instances where the aforementioned British legislation had shattered the remnants of the Shariat, the Muslim clergy had zero room to wiggle.

The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937 was abolished after Partition of India, which was the civilisational cost of our political independence. Sardar Patel’s fiery words in the Constituent Assembly are worth recalling:

“I want the consent of all minorities to change the course of history… whatever may be the credit for having won a Muslim homeland, please do not forget what the poor Muslims have suffered… I… appeal to believers in the two-nation theory to go and enjoy the fruits of their freedom and leave us here in peace.”

UCC—included in the Directive Principles—was clearly meant as a safeguard against future two-nation theorists. It is now common knowledge that for 75 years, it has practically remained a dead letter. Congress’ obsessive Muslim appeasement has ensured that the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937 continued to enforce a voiceless veto against the implementation of UCC. As a consequence, the power of the worst elements of the Islamic clergy has only grown to frightening levels. In this light, the Sidi Maula episode offers invaluable lessons.

AS A STUDENT OF our ancient and unbroken civilisation, in my view, UCC is only of secondary significance today. We missed that bus 70 years ago.

A focused, national effort at rediscovering our civilisational roots and values and ideals that had harmonised our society for millennia is the need of the hour. S Srikanta Sastri, a titanic scholar of the 20th century paints a beautiful portrait of this (emphases added):

“ The spiritual outlook that lies at the heart of Indian culture is the reason it is still alive and flourishing in the world… [Our civilisation] recognised… that perfect equality in all spheres is impossible… Therefore it attempted to mitigate the evil consequences of disparity by aiming at only the essentials. It reconciled the antagonism between rights and obligations, so that the individual by asserting his ‘inherent’ right might not break up social solidarity, nor could society impose such obligations as to cripple the spirit of individualism. Liberty and law were synthesized to achieve spiritual freedom.”

Today, Hindu society has become unrecognisable from what it had been, say, even 50 years ago. And this destruction has been achieved by vilifying and vandalising its core values which had been reinforced by beliefs, customs, rituals and practices. The bloodiest assault has been against the Hindu family system

I’m not technically competent to speak about the modalities and other aspects of implementing UCC. But a vital consideration must be made. UCC is not merely a legislative matter but a civilisational imperative. If we don’t make this vital distinction, the effort will be akin to applying band aid for treating cancer.

We can look at this issue from another perspective. History shows that each time India has flourished or renewed itself, it has done so by rediscovering its civilisational ideals and values, whose premise, generally speaking, is Dharma.

The aforementioned civilisational aspect has other dimensions as well. UCC is just one of several similar problems. Their roots can be traced back to what the legendary freedom fighter, journalist and litterateur, DV Gundappa (1887-1975) memorably wrote in his sunset years: till date, we have been unable to devise the most suitable political system by which we can govern ourselves. He makes another scathing observation in this context: the heavyweights who drafted our Constitution were bookish scholars notwithstanding their accomplishments. To this, we may add that a majority of them were thoroughly Westernised in their education and outlook. Thus it is unsurprising that Dharma, the word that is synonymous with Bharata, is conspicuously absent in a Constitution that should ideally protect it. Then, there were other influential ideologues like Jawaharlal Nehru who sincerely believed that they could somehow build a ‘new’ India by ignoring or annihilating its civilisation and culture. No country which has attempted this has succeeded or remained united.

THE CURRENT NARRATIVES around UCC ignore a point that should have ideally occupied centrestage: the near-total destruction of Hindu society through legislation.

Today, Hindu society has become unrecognisable from what it had been, say, even 50 years ago. And this destruction has been achieved by vilifying and vandalising its core values which had been reinforced by beliefs, customs, rituals and practices. The bloodiest assault has been against the Hindu family system.

Scores of luminaries, including judges, legal scholars, professors, academicians and politicians had foreseen precisely such outcomes when these laws were mooted in the 1950s. Constraints of space forbid a more detailed examination, so here are some excerpts from UC Sarkar’s 1958 work (emphases added):

l …there is no demand for the codification of Hindu law by the Hindu public. This is so, as most of the rules of Hindu law are now well-established and easily understandable. Had there been any necessity, it would have been expressed through public opinion.

l Hindu law, divorced from the Smritis and the Nibandhas, would be a contradiction in terms.

l The spirit of the code seems to be against everything Hindu. The attempt of the Code seems to change the culture and civilisation of the Hindus by legislation which is an absurdity in itself. The Code contemplates secularisation of everything which has been inextricably connected with Hindu religion and culture.

This historical survey shows that at no point was the Muslim community governed by the Shariat in toto throughout India. The existence of multiple schools of Islamic law—Hanafi, Shia, Ahmadiyya, etc—simply made this impossible and impractical

l The advocates of the Code were… the peculiar products of Western civilisation and Western education. They did not understand the underlying spirit or genius of the Hindu culture and religion… They were always attracted more by the exterior rather than by the intrinsic worth… those who were really benefited by Western contact were never unwise enough to denounce their own cultural achievements and contributions…

l As a matter of fact, without religion, philosophy and culture what is Hinduism and what is the contribution thereof? The piece of contemplated legislation is sure to lead to more chaos and confusion and lack of social discipline and order.

Which is exactly what has happened today. Chaos. Confusion. Societal disorder and breakdown.

Indian society has become de-Hinduised, and Hindus who seek to rediscover their roots have lost access to them because the vehicles that could take them there have all but vanished. What are derided as rituals, practices, customs, songs, festivals, and behavioural codes were precisely these vehicles. Sure, all these still exist but they exist largely in form, not in spirit and content. Overall, Hindu society has pretty much lost emotional access to its own culture and civilisation. And all this has happened majorly through legislation.

Thus, the honest question that needs to be asked—and honestly answered—in the discourse around UCC is this: What percentage of our intellectual and political leadership has a nuanced grasp of the cultural raw materials that had chiselled perhaps the greatest civilisation that human genius ever produced? Because, at its core, Bharatavarsha is and remains a spiritual civilisation. My studied conviction, reinforced by past masters, is that nothing better can replace it. It is still not too late to preserve its best elements.

/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/Cover-War-Shock-1.jpg)

More Columns

Kerala’s Tryst with the Nipah Virus Open

The secret that Pak military spokesperson wants to hide: Dad’s loyalty for Bin Laden Open

India hammers Pak air bases at Rafiqui, Murid, Chaklala, and Rahim Yar Khan in a show of unflinching force Open