Gandhi, the Father

THE BIRTH IN Durban on 22 May 1900 of Devadas, the last of their children, was not without some drama for Kasturba and Mohandas. The husband had, typically, read up a Gujarati self-instructor on childbirth so as to be prepared to ‘do it himself’ should the need arise. And, again typically with him, the need did arise for his self-taught, self-propelled expertise to be put to deft and timely use. The doctor and the midwife failed to show up. The father-to-be became an obstetrician and successfully so.

Kastur, who had been through four childbirths earlier, was not unfamiliar with labour. But she must have been hugely relieved when, that day, it was all over and done with. Perhaps she said ‘never again’ and thanked the Devas—Gods—of home confinements.

The newborn was named Devadas, servant of God.

Only the previous day, with Kastaur heavily gravid, Mohandas had been busy, drafting a felicitatory cable to Queen Victoria on the Monarch’s 81st birthday and asking the Natal government to forward it to London. He did not forget to remit Pound 1 as transmission charges.

The big picture and the small detail, public work and home duties moved in concert with him, though not always in harmony. Kastur, more than anyone else, knew both the jarring and the blending notes. Unusual and unexpected turns, interlaced with her husband’s public commitments, back to back, were standard in her life, her home, her world—which was wrapped around by his.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

‘Home’ and ‘the world’ were not different spheres for him. They stayed—and moved—together across continents, climes, and conditions, many of them largely if not entirely of his making. These conditions included, very particularly, the fading away, in rapidly growing degrees, of the distinction between home and society, between his family and other families, between the future of his descendants and the future of others, persons, causes, and country.

He was surrounded by and soaked in ‘family matters’ throughout his life of nearly eight decades.

The number of people he looked upon and even described as being no different from his own children was large. The number of those who looked upon themselves as being no different from his own children was larger. Both he and Kasturba as she came to be known very early into her married life widened the walls of their home, raised its roof, opened its doors to admit—and welcome—not only cousins, nephews and nieces, and their spouses, but also a host of those many from all over the world who joined their energies to his life’s missions.

He would, as a political prisoner, accept visitors’ calls allowed to his children with natural happiness but if similar access was not provided to those others who looked upon him as a father or mentor, he would do without his own children’s visits. No special privileges were reserved by him for his biological descendants and no hardship withheld from them.

And yet there was that space he carved out of the borderless province of his public life, the room he cleared out of the vast lodging house of his public endeavours where family was, simply, family. There was a primary-ness to that unit, if not primacy. There was an exceptionality to it if no exclusivity. His family of wife, children, children-in-law, and grandchildren was for him the umbra of kith within concentric circles of penumbral kin, the world of the home distinct yet indistinguishably merging into the home of the world.

A very intense man, house holding with an obsessive attention to detail, holding beliefs with passion, holding friends with devotion, holding views with tenacity, lay at the core of the leader who held India’s political imagination for over three decades. A restless, intense, house-holding Mohandas propelled the man who led India out of the British Empire through many resounding successes and not a few notable reverses. The same Mohandas spurred the same man, in another theatre, who strove ceaselessly to reform India’s social mores with success crowning some initiatives, and totally eluding others.

Within the breathlessly hectic sequence of the disciplined mass movements that he started in South Africa in 1908 and concluded some forty years later in India, lies the story of an engaged and engaging husband, father, father-in-law, cousin, and uncle who was constantly called upon, by his conscience and his sense of the interconnectedness of things, to apply his principles to home life. His successes and failures at home matched and mirrored those in the public sphere. These were quietly internalized. Failures—and failings—remained open scars, as the letters he wrote to his intimates, show.

The home language was Gujarati, the home idiom familiar, frank but unvaryingly respectful. Gandhi’s letters to his wife and their sons and daughters-in-law bear testimony to that equation.

The letters that he wrote to Devadas are in his fluent, cultivated Gujarati, holding proverbs and literary allusions, written with precision and deliberation in what publishers would call ‘print-ready’ condition. He addresses Devadas, as he does his other children and those younger and in ‘filial’ bonds with him, as Chiranjivi Devadas, shortened to ‘Chi. Devadas’, the prefix meaning ‘Long Living’—a wish and a blessing. While addressing the envelope, he invariably switches to English, for the ease of the postal authorities. And when doing so, he spells his son’s name ‘Devdas’, without the ‘a’ between the ‘v’ and the ‘d’, the vowel being introduced by Devadas at some early point in his life to better accord phonetically with appropriate, correct pronunciation. A person may have his name chosen for him, but he is entitled to choose the spelling of it—a compromise which reflected Devadas’ and his siblings’ equation with their father. Gandhi set the base according to his sights, his sons built on it according to theirs.

And he signs off, in each one of them, almost without exception, with ‘Bapu na ashirvad’, meaning ‘blessings from Bapu’. The letter can differ in tone, texture, and intent and give a range of epistolary ‘gifts’— encouragement, praise, criticism, and admonition bordering on a rebuke. But the blessing remains a constant. Was that plain routine, a mechanical form? Nothing about Gandhi was the work of habit. Each letter was and brought a conscious blessing. That was a given. And each letter became a segment in the growing tapestry of his life’s story.

That story is well documented in his autobiography which was written for the world to read, if it cared to do so. It is also tellingly reflected in the letters he wrote to his kith and kin in times of joy and sorrow, of trouble and anxiety and also in none of these but in moments of plain emptiness such as when in prison his thoughts drifted to his family with a variety of emotions, worries, hopes, and prayers which were those of a householder, regardless of being called by the world, ‘Mahatma’.

Mohandas had come to be called ‘Mahatma’ (Great Soul) at age 40 by one of his earliest and lifelong friends, Dr Pranjivan Mehta. That doctor-lawyer-jeweller used the expression in a letter he wrote to the liberal statesman Gopal Krishna Gokhale (1866-1915) in 1909. Did Gandhi know that Mehta had just used an expression that would become part of his name, his persona forever? We cannot be sure, but we do know that the defining epithet made no difference to his everyday life.

A SWING FROM THE personal to the general, from the intimate to the reflective, lies at the heart of his letters to his family. The most weightlessly private in them mingles with the weightiest of public concerns, tying the seemingly unimportant with the obviously serious. The expressing of a passing familial anxiety in these letters can fold itself and disappear into a statement made in the very next sentence, of some abiding principle or preoccupation. The offering of advice, solutions, and nostrums is set against the backdrop of an occurrence of national, even international salience. There are a microscope and a telescope at work in these letters which, one can be sure, not only helped but also exasperated, inspired, and perplexed their recipients. They certainly did the youngest of the four sons.

That home stayed ‘home’ even as it moved from dwelling after dwelling across eight cities—Porbandar, Rajkot, London, Durban, Johannesburg, Bombay, Ahmedabad, and ‘collective communities’ or Ashrams on the rims of towns: Durban-Phoenix, Johannesburg-Tolstoy Farm, Ahmedabad-Sabarmati, and Wardha-Sewagram not excluding scores of temporary venues where he lived over extended periods with his family of natural and ‘co-opted’ origination. It also stayed home, curiously and famously over the nearly six years—about half a year in South Africa and five and a half years over different spells in India—that he spent in jail as a result of his political campaigns which did not quite separate him from family.

His eldest son Harilal, then all of twenty-one and he were together in Volksrust and Pretoria jails in 1909, the father admiring his son’s guts. Kasturba was allowed by the British Raj to be in jail with her husband on more than one occasion in India. Kasturba was to die on 22 February 1944, in the Aga Khan’s Prison Palace in Poona, her hand clasped by her husband during his—and her—last imprisoning. His extended family, in the sense of political and other associates was also often in the same jail as he was in, with access to him.

Home also became ‘home’ in the intangible form of home waves that throbbed through the torrent of letters sent and received.

Most letters that came into those sites, into Gandhi’s hands, have gone into the sealed attics of time. Before he acquired secretarial help, and even after that, he chose which letters to keep, which to tear up, which to pass on to others who then did what he told them to do with them, including tearing them up after reading them. Some, like those from Pranjivan Mehta, were destroyed by Gandhi because the writer wanted him to for reasons, one might imagine, of current privacy, at a great cost to future understanding. Many that went out from those, out from Gandhi’s unceasingly active pencils and pens, have survived. These form part of the audaciously successful 100-volume compilation of his letters and writings in the journals he edited and elsewhere, and the texts of the books he wrote—The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi.

Some letters written by Gandhi have remained out of the collection and will hopefully get included in supplementary volumes. Others may not enter that series but will enrich other publications, like the letters Gandhi wrote to Devadas. They date from 5 March 1914 when Gandhi is 45 and Devadas 14. They end with a letter dated 14 January 1948 that the father at 79 wrote to his son when the son was 48. The first letter, obviously a reply to one from the son, begins with ‘Improve your handwriting’. Kasturba is seriously ill and Gandhi’s thoughts are about mortality. He nears the end of the letter with ‘Realising then, the fate of the body, we should cultivate goodness and disinterestedness’. And, as if reminding himself that the boy is but fourteen, he adds ‘Disinterestedness does not mean outward indifference...’ No simple lesson—or mix of lessons—for a boy scared about losing his mother to death.

Gandhi’s letter writing was a non-stop pre-occupation verging on an obsession. He wrote them by day, he wrote them by night, he wrote them from aboard trains, steamers, both right and left hands being pressed into service to rest one when tired out. And when both had to be rested, he dictated the letters.

All letters to his sons and to their wives are in Gujarati, barring those to his youngest daughter-in-law, Lakshmi to whom he writes in Hindi because he cannot, to his regret, write to her easily enough in Tamil.

Is there anything in the content or tenor of the letters to Devadas, in the application of care, the bestowal of attention and the offering of advice, appreciation, and admonition that mark them out from letters written by the father to his other sons?

No, there is not. In the affection, the core of tenderness, concern, and not un-often, great anxiety, the letters that Harilal, Manilal, Ramdas, and Devadas received are identical. The father was completely and equally ‘into’ their lives, and those of their families. But there is in the letters to each of his sons that ‘something special’ which is exclusive to the recipient’s nature, his condition, and situation.

The ‘something special’ in Gandhi’s letters to Devadas is the shared vein of political reflection, of consultation on public matters, of the sharing of views on what is commonly called ‘men and matters’. This is so marked that one regrets the absence of Devadas’ ‘in-coming’ letters which had either been occasioned by Gandhi’s or to which Gandhi was responding. Many have been accessioned at Sabarmati, many more not. A one-to-one matching of the letters would have led to a far more fulfilling reading. We have, for the most part, to infer what Devadas wrote to his father.

Gandhi observed his sons as closely as they looked to and up to him. And he made his own assessments of them which were always inspired by a desire to be fair to them and to rectify what he felt was wrong about what they were doing.

His letters are loving. They can also, as he told his nephew Jamnadas, scorch.

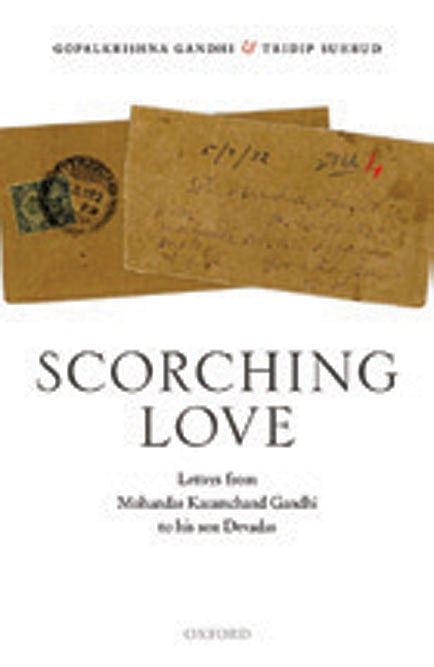

(This is an edited excerpt from Scorching Love: Letters from Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to His Son, Devadas, edited by Gopalkrishna Gandhi and Tridip Suhrud)