An Opportunity in the Gyanvapi Dispute

The righting of historical wrongs prevents the past from compromising the future

Arvind Sharma

Arvind Sharma

Arvind Sharma

Arvind Sharma

|

08 Jul, 2022

|

08 Jul, 2022

/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/Gyanvapi1.jpg)

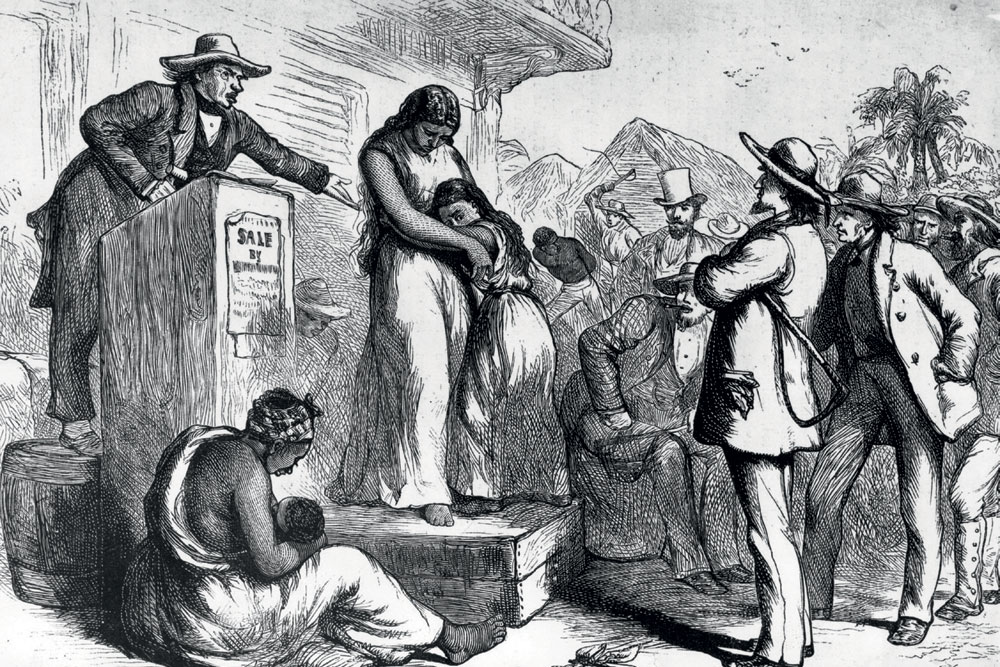

An aerial view of the Gyanvapi mosque and the Kashi Vishwanath temple in Varanasi (Photo: AP)

THE SPATE OF SUITS demanding the restoration of the original character of several holy places in India basically involves the issue of the righting of historical wrongs. This is the elephant in the room. And those who have spotted the elephant have already identified it as an elephantine problem which is best left undisturbed. Others however feel, to change the metaphor, that the genie is now out of the bottle.

I sense in these debates a certain reluctance to accept the case for the righting of historical wrongs, even by people of goodwill. In this essay, I would like to address some of their concerns. I begin by taking the various objections raised against the righting of historical wrongs into account.

First, one objection takes the form of the following argument: How could the present generation be held responsible for the actions of a previous generation?

Thus, during the agitation leading up to the extension of affirmative action to backward classes beyond the former untouchables in India, the plea was heard: “I am being made to pay for the sins of my ancestors,” from the Dvijas or twice-born Hindus. Whenever the question of compensating the Blacks for slavery comes up in the US, white Americans similarly insist that as they don’t own slaves, why should they be made to pay for what their forefathers may have done? And so on.

Several responses are possible here.

One would be to point out that the present generation has also benefited from the iniquitous arrangements of the past, and therefore cannot be considered totally innocent in the matter. Thus the present generation, therefore, may be at least liable to the extent it might have benefited from the past arrangement. This should dispel the air of injured innocence with which some of the beneficiaries of past wrongs may respond when asked to consider the prospect of the righting of historical wrongs.

Another response would be to develop the above point even further and offer the following argument—that the position in society the privileged now enjoy is a product of the same process which involved the immiseration of those who now constitute the underprivileged. The prosperous white citizen of the US today and the impoverished Black citizen of that same country are parts of the same process. They are two sides of the same coin; they are, better still, two sides of the same ledger. So the claim to the righting of historical wrongs can only be ignored in a cyclopean view of history.

Those who start feeling uncomfortable when they seem to become liable for having to redress the historical wrongs involved might wish to consider a third argument, an ethical one, which tries to distinguish between guilt and responsibility. Some ethicists argue that there is no such thing as collective guilt; guilt is individual and non-transferable. By this criterion, the present-day American need not feel guilty about slavery; the present-day British need not feel guilty about British colonialism; the present-day upper-caste Hindu need not feel guilty about untouchability if he or she does not practise it; the present-day Indian Muslim need not feel guilty about the unsavoury aspects of medieval Muslim rule over India; the modern male need not feel guilty about how women were treated in the past, and so on.

However, even a person who need not feel guilty may feel some responsibility for being involved, albeit involuntarily, in a system which produced these wrongs and may not begrudge the steps undertaken to rectify the situation. And this would be all the more true if the person possessed a social conscience.

These are some of the arguments which help us deal with the inter-generational dimension of the situation. After all, we don’t come up with any such arguments when we are about to receive a legacy!

Second, another frequently met objection is to ask: How far is one to go? Do the Italians have to compensate the British for ruling over them as Romans in the remote past? Do the Norman invaders have to make amends for invading Britain in 1066? Or, closer to home, do the Aryans who allegedly came to India from Central Asia have to compensate the Dravidians? Do the Hindus compensate the Buddhists whom they allegedly oppressed? India is a palimpsest; it has layers upon layers of history. How far is one going to peel it?

One begins with the present. American slavery is not as remote as Roman or Greek slavery. Muslim destruction of Hindu temples is not as remote as the alleged Aryan-Dravidian conflict. So those cases in which the connection of the past and the present has not been obscured by the passage of time could be taken up first. A society in which historical wrongs have not been addressed is not a healthy society

Let us consider a parallel situation to shed more light on this line of reasoning. Suppose we were to catch a thief red-handed, but his or her lawyer were to argue: How far do you intend to go? How can you arrest this person until you have arrested all the thieves in the world? Why are you picking on this thief and discriminating against him?

We are not likely to be impressed by such arguments.

I think the response here has to be that one begins with the present. American slavery is not as remote as Roman or Greek slavery. Muslim destruction of Hindu temples is not as remote as the alleged Aryan-Dravidian conflict, and so on. So those cases in which the connection of the past and the present has not been obscured by the passage of time could be taken up first.

Third, yet another objection is sometimes raised against the righting of historical wrongs. According to this objection, if we do so, we are likely to fixate on a society’s past instead of encouraging it to look towards the future. In a sense then, seeking the righting of historical wrongs makes the past an enemy of the present.

A response to this line of argument could be that a society in which historical wrongs have not been addressed is not a healthy society; it is not a society functioning optimally. The righting of historical wrongs prevents the past from compromising a society’s future. Mention may be made here of the study of societal trauma and how its consequences ramify through several generations in the form of intergenerational trauma, a phenomenon which can manifest as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

One also needs to keep in mind the fact that the righting of historical wrongs often involves the redistribution of resources in favour of the dispossessed. This is bound to contribute towards a healthier and happier society in future.

Fourth, another objection pertains to the manner in which the historical wrongs can be compensated. It is pointed out that the various individuals that constitute the groups which may be historically liable may not be able to bear the burden individually. For instance, the amount of wealth transferred by the British from India, during their rule, has been calculated by Utsa Patnaik at around $450 trillion, which amounts to several times the gross domestic product (GDP) of the UK. By this account, it might be virtually impossible to compensate India for such transfer of wealth.

Two points need to be borne in mind with this connection. The first rests on the distinction between individual and institutional restitution. Consider, for instance, the 47,000 temples allegedly destroyed during the period of Muslim rule over India. The responsibility for compensating any party for this historical wrong should rest with the institutions of the Islamic world and not so much on individual Muslims. That is to say, perhaps the compensation for such destruction could be met out of the Islamic institution of Zakat, or through the Waqf property, which is held by Islamic institutions in India. Individual Muslims should not feel the need to bear the burden.

The prosperous White citizen of the US today and the impoverished Black citizen of that same country are parts of the same process. So the claim to the righting of historical wrongs can only be ignored in a Cyclopean view of history

The second distinction has to do with whether the compensation has to be delivered in one stroke, or in instalments over time. It is easy to see that the staggering amount which the UK is supposedly liable to pay India could seem too much if it is to be paid at one-go. But this may become manageable if the payment is stretched out over several generations, just as the transfer of wealth from India to the UK also covered several generations.

We can see this principle at work in the way reservations have been used in India as a way of compensating the lower castes and women for past wrongs.

IN THE DISCUSSION so far, the various objections to the righting of historical wrongs were examined and an effort was made to answer them. In this sense, the discussion was negative in character. In what follows, I try to develop a positive case for the righting of historical wrongs.

I would like to begin by asking the question: When does an act performed by anyone become a wrong? It could be argued that an act becomes a wrong when some punishment is laid down for performing it. If one person kills another, it is merely a killing, as in war; it becomes murder when a punishment is laid down for doing it. It is the provision of punishment which converts an act into a crime. Marital rape, for instance, is not yet a legal (as distinguished from a moral) wrong in India but it is in Canada, because a punishment is laid down for it.

One is now ready to make the further point that as a society became civilised, acts which could be considered morally unworthy, but were not earlier considered wrong, came to be treated as wrongs. Slavery is an obvious example here. An even more striking example is provided by how the category of war crimes came into play at the Nuremberg Trials. What one needs to keep in mind is that, prior to World War II, everything was considered fair in war (and love). However, the horrors of World War II compelled humanity to make some actions, undertaken even in war, justiciable—that is to say, capable of being brought to court.

Perhaps, as humanity progresses, it becomes more morally sensitive and as it becomes morally sensitive, it becomes legally inclusive, in the sense of making even those acts legally answerable which were earlier not so. It seems to me now that we are on the cusp of a similar forward movement. Thanks to the feminist movement, for instance, acts against women which were earlier not considered wrongs, and were dismissed with a shrug, are now recognised as wrongs. Just think of the “Me Too” movement.

Perhaps we need to remind ourselves here of the famous statement by Walter Benjamin: “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism.” This statement should remind us that the great achievements of ancient India also have their shadow-side, in the form of untouchability, caste discrimination, and so on. Similarly, the glorious achievements of Islamic civilisation also have their shadow-side: the destruction of earlier cultures, slavery, and iconoclasm on an industrial scale. The glorious achievements of modern civilisation also have their shadow-side in colonialism, slavery, and genocide. So far, we have treated these shadow-sides of these cultures as merely historical facts, without any ethical implication. The suggestion here is to ethicise this discourse, in keeping with our earlier formulation that, as a civilisation progresses, acts which were earlier considered acceptable cease to be ethically acceptable and are even made legally actionable.

Prior to World War II, everything was considered fair in war. However, the horrors of World War II compelled humanity to make some actions, undertaken even in war, justiciable—that is to say, capable of being brought to court, as at Nuremberg

From this point of view, we now have this great opportunity of making, for instance, colonialism justiciable. India is in a unique position to take the initiative in this respect. India has been at the receiving end of two great colonisations in its history—one, of course, at the hands of British or Western powers, but one also at the hands, as J Sai Deepak has pointed out, of what he calls Middle Eastern colonialism. Both were extremely damaging for India; Middle Eastern colonialism especially so in terms of the physical destruction of its religious landscape, and the British in terms of its economy.

We in India should, therefore, reinforce our efforts to correct the wrongs against the lower castes and women in India, even as we demand the righting of these two historical wrongs vigorously. What was once dismissed as “Oh, that’s history” will thereby be made justiciable; other countries will follow suit, and a new chapter will be written in the progressive history of the world.

And Kashi will once again make the world shine, true to its name.

About The Author

MOst Popular

3

/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/Cover-Shubman-Gill-1.jpg)

More Columns

Nimisha Priya’s Fate Hangs In Balance, As Govt Admits It Can’t Do Much Open

Roots of the Raga Abhilasha Ojha

An Erotic Novel Spotlights Perimenopause Nandini Nair