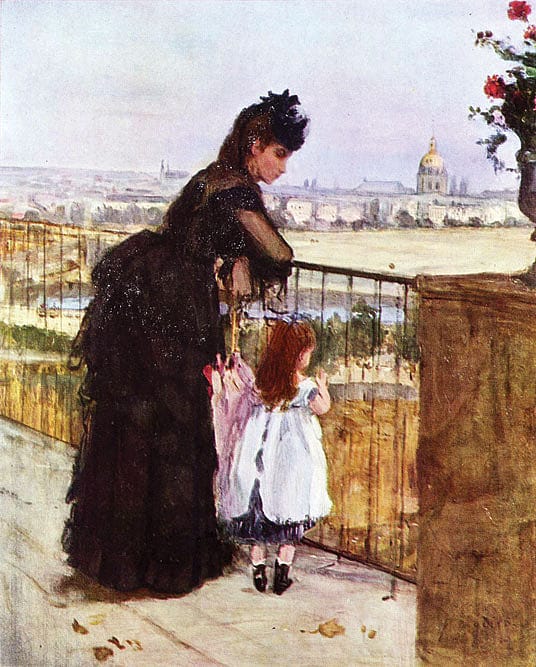

The Woman on the Balcony

A woman clad in a black chiffon-like dress leans over the railing of a balcony. The ruffles of her dress cover her from neck to toe. Only the flesh of her arms can be seen through the transparency of the sleeves. The woman holds a closed umbrella, which stands on the ground. A small girl, shorter than the umbrella, leans beside the woman, peering through the bar of the railings. The woman's body arches in a way that seems to shelter the girl while also giving her space. A canal and a city spread out before them. A dome resembling the Basilica of the Sacred Heart of Paris towers above the cityscape. While the woman and the child face the direction of the city, their interest lies elsewhere. They both look lost in their thoughts, in the grip of their interior world and not the exterior. The black of the woman's dress suggests funeral wear. The shut umbrella hints that they've either just returned or are heading outside.

To look at Berthe Morisot's On the Balcony (also called Woman and Child on the Balcony), painted in 1872, is to feel an uncanny affinity. Morisot's woman in black could be any of us in 2020. She stares out at the city from a balcony which holds her in and which hands her the outside. When Morisot, one of the great French, female painters of Impressionism, painted this watercolour, with touches of gouache, in the 19th century, women were still denied access to the public sphere. This painting shows the clear demarcation between the public and private, where the balcony acts as the portal between the two. It also highlights the remoteness of the city. One can see it, but one has little interest in or access to it. In the 19th century, the city was essentially out of bounds for a woman (unless she was escorted); in a post-corona world, we now see the city not as the hive of our lives but as a Petri dish for viruses.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

While cities across the world open up, the risks from Covid-19 increase manifold. The unlocking doesn't suggest a victory over the virus, rather it shows our fallibility when dealing with risks. For reasons of public (and personal) health, we should continue to remain cloistered in our homes, but economies and our mind-sets dictate otherwise. Till the vaccine has been discovered and administered, or herd immunity develops, the house will continue to be our realm.

The house is not free from perils. We know from anecdotes, data, reports (and perhaps, even personally) that the pandemic has fractured relationships, increased domestic violence and made the house a site of adversity. But even within the confines of home, moments of relief, maybe even rebellion, can be found. Traditionally, the home has always been considered the woman's space; women were not to loiter the streets, women were not to claim the public sphere.

Today, perhaps, we can see a hint of how the home can be reclaimed. The outside world is now a danger to both men and women. Without the demands of the outside world, the home (for the fortunate) becomes a nest from the public sphere. It will take some time before films, books and art emerge from the pandemic and tell us how the home has evolved during this time. But in the interim, we can look to ads and short movies that reveal the possibilities of home.

The Asian paints ad campaign, 'Har Ghar Chup Chaap Se Kehta Hai', which promoted its #StayHomeStaySafe series and came out in April 2020, is a good example of how the house is being reimagined. The ad series uses stills of real families in their households engaged in leisure and work. While an ad, of course, sells a product, it also creates an aspirational and lived reality. The Asian paints ad consists of a series of shots, such as a man on all fours scrubbing the bathroom floor, tile by tile, with a brush; a woman on a ladder changing a light bulb; a man putting a toddler to sleep on his chest. With the choice of images taken from actual households, the ads tell us that happiness can be created when families stay home together. While it might seem contrived to the cynical viewer, the ad also equals out gender roles: if a woman can climb a ladder to change a light bulb, a man can put a baby to sleep. While gender (most often) defines and cements roles at homes, this ad (less than a minute long) shows us the possibility of parity.

Nandita Das' lockdown movie on domestic violence, Listen to Her, released on May 25th, provides a powerful message about gender disparities. Das plays the role of a professional handling work calls and presentations, a mother answering her son's queries, a wife heeding the demands of her husband and the whistles of a pressure cooker, and a woman trying to rescue another woman from an abusive relationship. In just seven minutes, Das exposes the many challenges faced by a woman, ranging from demands for time, care and attention to cruel physical abuse. Towards the end of the movie, as Das listens to a woman on the phone recounting her travails with her partner, she tells her own male partner, 'You do it', when he asks her to run yet another household chore. Just those three words—'you', 'do', 'it'—establish Das' moment of rebellion in the home space. With that single rebuke to her husband and by closing the door on him and listening to the aggrieved woman on her phone, she implements her choice. She chooses to be a comrade to the woman, and not a clerk of her husband.

Today, as our opportunities to go out and meet people plummet, or as our occasions to dress up vanish, one often wonders when one will wear a saree next, or stilettos, or jewellery. And while one can always revel in accoutrements and accessories, right now all of it seems pointless, outlandish, even. Staying at home has bestowed upon us the 'fashion of privacy'. It is a fashion that rejects the donning of belts and bras. It spurns trousers and tight-fits. It looks askance upon make-up and make-overs. A July 2020 article in The Guardian was appropriately headlined: 'The thought of skinny jeans makes me ill!' The article asked whether the pandemic had taken jeans to the graveyard. What were the new rules of beauty?

I often ask myself, if the new rules mean no rules, the greying of hair, the non-threading of hair? Are we going to embrace leisure wear for good and abandon 'formals' altogether? Are we going to finally concede that 'office shoes' serve no purpose other than shoe bites?

Reading the article, I kept thinking how the 'fashion of privacy' is dawning upon us. Previously, fashion was essentially what we wore for the outside world, it hinged on us creating our most confident face and avatar for the faces and avatars that we would meet. Fashion helps us conjure up our personalities for ourselves and for others. But if the 'other' is removed from the equation, then we have in-house fashion. It is a fashion that conflates comfort with confidence, ease with poise.

A painting that richly illustrates the fashion of privacy, which reminds us that fashion is not only about what we wear but how we wear it, is Thérèse Dreaming (1938) by Balthus. A first study of the painting will show a girl caught in a moment of leisure and repose in her own room in a moment of solitude. She seems to have just fed her cat, who licks from a bowl near her feet. The girl's eyes are gently shut. Her arms are held together above her head, her limbs are not a shield to her body, instead they are their own entities. She appears completely at ease. She could be any woman from today in her own room. In the expression of her face and the positioning of her arms and legs one senses a freedom from outsider eyes.

The viewer's interpretation of the portrait, however, is complicated by the fact that the artist is Balthus who is known to have asked underage models to pose for him. This, of course, raises the troubling question of consent and power. Balthus and his art have been examined and re-examined by legions of scholars and critics over time. Some hail him, others condemn him.

But today, it is in Lauren Elkin's (author of the excellent Flâneuse: Women Walk the City) examination of this portrait that I find resonance. She writes in Frieze, a magazine on art and culture, in the December 2017 issue, 'It is not the work of art to make us feel safe; if it does, it probably isn't art at all.' Addressing a controversy around the work, she adds, 'Our culture is terrified of sexually-awakened girls; controlling the way we look at Thérèse Dreaming would erase an interior life.' Like Elkin, I too choose to see this portrait not as a girl in a vulnerable position, but as a girl in a moment of privacy.

It is a painting that reminds one of every parent and grandparent who has told girls to sit with their legs together. It is a painting that shows us that Thérèse is present in the room physically, but mentally she is far, far away. And that is why this painting speaks directly to our Covid -19 times. It is about rebelling against societal diktats in one's own room, it is about travelling distances within one's room. It is about seizing agency in one's own den. The room itself can grow into a platform for protest.

The Asian paints ad also displays how space within the home is being reconfirmed as we are all forced to stay in and for longer. The dining room floor now morphs into a picnic space, with a rug laid out on the floor and a basket of fruit at the centre; the dining table becomes office; the balcony with plants becomes a wonderworld; and school is no farther than a door away. Over the last few decades, as a society we've always relied on the outside for adventure and experiences. And while that will always be the default mode, we are now slowly adapting. As we continue to gauge the outside with suspicion, it is our homes that we now pay more attention to. We clean them ourselves, we beautify them, we wrap them around ourselves to create our bespoke cocoon.

We've all become the woman and the child on the balcony. The cityscape might spread out before us, but it's not ours to enter. To stay at home is to be limited, but at these times, it also affords us autonomy and security. Urban spaces and crowds have always excited us because of their endless possibilities, the chance to meet strangers and stumble upon happenstance. But in a post-corona world, cities have become liabilities, we now wrestle our way through them because of compulsion and not choice. As we are forced to unfriend them, it is at home that we will have to find our world.