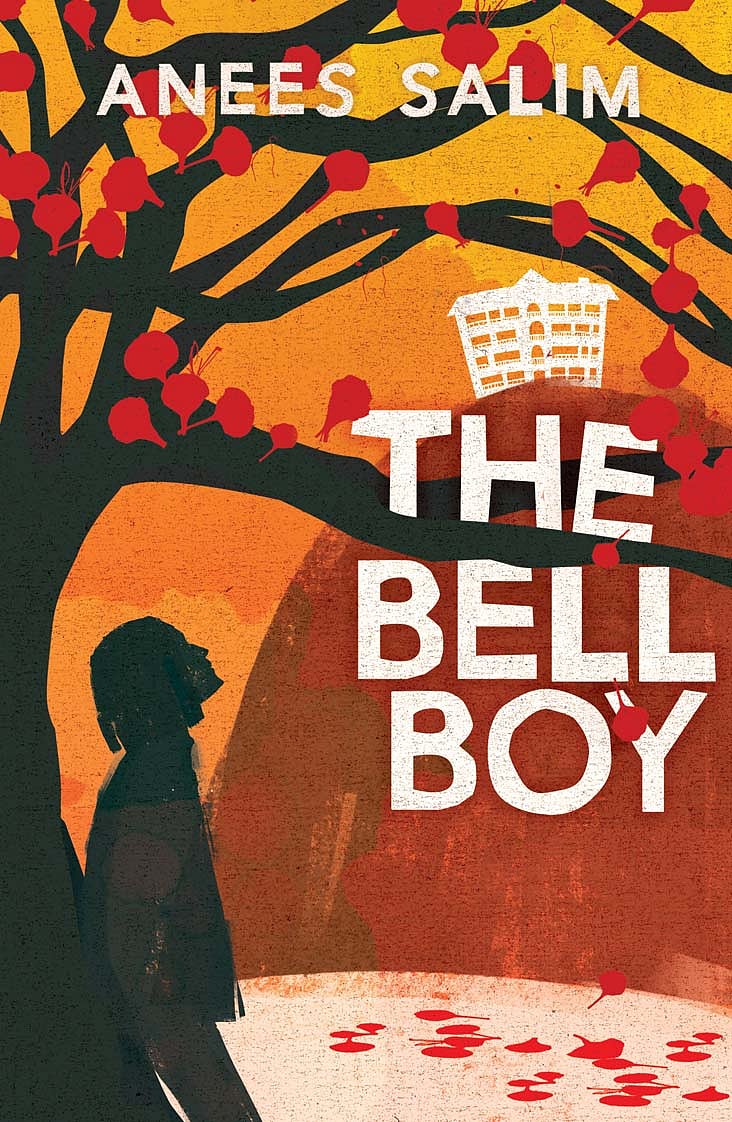

The Bellboy

AS THEY WOULD GO TO A holy city to die, people came to Paradise Lodge to end their lives. Young and old. Men and women. Able-bodied and ailing. Like migratory birds, they arrived from places Latif had never heard of. It was as if it was the closest point to the after world, as close to heaven as the weatherworn jetty that stood to the back of the lodge, across a narrow, slimy, canal.

From the top of the highway, Latif had his first glimpse of the lodge; a tallish building that had not seen a lick of paint in years, and wore a sombre brown, akin to the sepia of holy cities. The huge bay window on the fifth floor had a few missing panes and looked like a gaping mouth with the front teeth knocked out. As he walked nervously down the highway, Latif thought the lodge had the appearance of a demented old man, smiling blankly at a younger clump of architecture.

Over time, Latif had started to suspect that people checked into the run-down, short-staffed lodge only to die. Some survived, changing their minds at the last moment, probably daunted by fear or guilt, or even by the advertisement for an upcoming lottery that drifted in through an open window. Some simply succumbed. A fat ledger, made fatter by the dog-eared pages, sat on the counter in the lobby, a pen suspended from a twine glued to its spine. Latif would kill time turning its yellowing leaves, reading the entries as solemnly as one read headstones. His eyes would linger over the names against which the checkout details were not recorded. Blurry red lines ran vertically across the pages, creating columns, and under the one titled Purpose of Visit, guests wrote either Business or Personal, never To Die. Tracing the dead guests’ handwriting, usually a shaky scrawl or, occasionally, a surprising copperplate, he often wondered how they had bid farewell to their families before leaving home for the last time, and if their hands had shaken when they wrote in the ledger.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

When the people on his island asked after his job in the town Latif pretended to love it, but he secretly thought of the lodge as a house of death and decay. His first day at work had left him shattered, opinionated. He had carried a freshly laundered bedsheet down a gloomy corridor to Room No. 117 and spent a long time knocking on the door. He then reported the unresponsive guest to the manager who clicked his tongue and collected a bunch of keys from the drawer. The manager was a stout middle-aged man who never ceased to remind Latif of a savage-looking Mexican footballer he had seen on a neighbour’s TV. As they walked down the corridor, he wondered if he should tell the manager that he had a doppelganger in Mexico, who played on pitches that looked like pastel green carpets. But it was his first day at work and he did not know if the manager liked football enough to be flattered by such a comparison. And the manager had the angry eyes of one who did not welcome conversations, so he decided to follow him in silence, imagining them to be two tough wardens proceeding to an even tougher inmate’s cell, the keys jingling in sync with his superior’s laboured gait.

The manager hammered on the door for a few minutes, then chose a key from the bunch and slipped it into the hole. Latif didn’t expect the door to open, but it did, and he hid himself behind the manager, anticipating something bad, and then gathered enough courage to peek into the dingy little room. The guest hung from the ceiling, his face flushed with an almost comical look, suggesting there was no dark side to death, that death was just another laughing matter. Latif immediately wanted to walk away from the lodge, never to return. But the thought of his dead father’s photograph on the living room wall, of the lunch his mother had packed for him, and the library-like silence of his insular village held him there.

The manager strode into the room, skirting the pool of urine that had collected on the floor beneath the dead man, and opened the cupboard in the corner. Latif remained in the corridor and looked past the hanging guest at a window that framed the branches of a gulmohar tree—full of flowers, full of birds, full of life. The manager picked up a folded sheet of paper from the middle rack and read it cursorily. Then he put it back and anchored it with a ballpoint pen. Next, he picked up a wallet and opened it. Latif, new to the job and even newer to the scenario of a suicide, watched uncertainly as the manager extracted a few currencies from the wallet and pushed them into his shirt pocket. He turned his head away and glanced towards the jetty and watched the afternoon boat pull away. Had he caught it, he would have been home in less than an hour, lying on the narrow bed in his bare little room that afforded a distant view of the olive waterbody through a coconut grove. The next boat was due in an hour, and he knew he would not take it either. No, he would catch the one that departed just before daybreak and take the early morning boat back to work a day later, every second day. That was the arrangement with the lodge. However much he wanted to quit, his father’s photograph on the wall and the lunch his mother cooked for him in the small hours would keep him tethered to the lodge.

The manager locked the room and walked back to the lobby, and Latif trailed him nervously. Barely into the third hour of his first job, he had already witnessed a dead man being looted. Abruptly, he felt grown up. An eyewitness to oddities. A keeper of secrets. Until a month ago, his mother had worked in a small factory that sat at the edge of the island, next to the pier, shelling cashews. She smelt of woodsmoke and cashew apples, even after she left the job. Handling smouldering cashew shells all day had left her fingers spongy, their skin scarred and smelly, rough like sandpaper. When she could no longer hold the club that cracked cashews open, she left the job reluctantly. It was from the owner of Quilon Cashews that she heard about the vacancy at the lodge. More than the money it brought, what appealed to her about the job was the small chance of Latif getting lost in the mainland. A boat ride to the town, a leap over the canal, and he was at work. A boat ride to the island, a ten-minute walk from the pier, and he was home. If the boat capsized, he could swim either to his workplace or home, depending on where the vessel sank. He was a good swimmer. Everyone on the island was.

The manager dropped the keys into the drawer, smoked a cigarette and only then did he pick up the phone to report Room No. 117 to the authorities. Latif expected the police to arrive as soon as the phone was dropped to the cradle, the sirens of the police jeep and the ambulance overlapping onto one another. The police took hours to come. The ambulance would not arrive till late afternoon. The drive under the gulmohar was a red carpet by then, speckled with the yellow of anthers, and the police jeep came to a halt just short of the floral setting.

‘The guest is not responding,’ the manager told the police.

‘Didn’t you try to open the door?’ a policeman asked.

‘No, we were waiting for you to come.’

Latif followed the policemen and the manager down the corridor, careful not to tread on the shadows of the capped heads. He no longer thought of himself as a jail warden and the dead man as a feral inmate. He was numb in a way he had never been, not even when he heard of his father’s death, he found himself completely empty of thoughts, grief and imagination. The manager chose the wrong key from the bunch and tried to open the door. He chose three more wrong keys before using the right one. When the door fell open the manager recoiled theatrically, his mouth half open in feigned shock. Latif remembered the Mexican footballer being tripped to the ground and rolling on the pitch in fake pain, soliciting a penalty kick. A new detail caught his eye; the front of the dead man’s trousers was wet, and his big toes dribbled to the floor, as slowly as a hospital drip. The room now smelt strongly of urine.

A policeman picked up the suicide note from the cupboard and read it in a patch of sunlight while his colleague dragged a chair to the window and started to write on a clipboard. He gave the dead body long, occasional, glances, as if drawing inspiration from the deceased to write a story. Latif did not wait for the rest of the proceedings. Hurrying down the corridor, he grabbed the lunch his mother had cooked for him in the light of a sooty 40-watt bulb, using a spoon to save the torments that the condiments gave her permanently bruised fingers. He sat down on a bench in the lobby and opened the oily paper parcel. Then he ran out, the lunch in his hands, and made himself sick under the star fruit tree at the back of the lodge.

AMONG THE LOOSELY STRUNG

archipelago, his island was the farthest from the town and the biggest of the six. Where the river met the land there started the legend of Manto Island. The bust of Manto, a fat man with a handlebar moustache and a double chin, sat on a pedestal near the pier, facing the river, discoloured and defaced. Though the bust was the colour of tar, Latif knew Manto was white, that he served as an administrator to the archipelago during the colonial period. Though the sculptor had squeezed a half-smile onto Manto’s thick lips, Latif doubted if the administrator had ever smiled at the natives until he had to take a boat out of the archipelago and then a ship out of the newly born India. Every time he passed the bust, Latif wondered what had qualified Manto to be immortalised in granite, and what folly had he committed that his bust be vandalised with flint and grease. The island no longer paid any attention to the statue, even birds had stopped sitting on its head and smearing it with their droppings. And when Latif saw it on the neighbour’s TV his heart leapt, and when he spotted many villagers on the screen—uncles, cousins, neighbours, the young tailor who stitched his clothes and the old barber who cut his hair— he wanted to call them out by their names. But, in spite of the islanders smiling shyly at the camera, the report spelled doom for Manto Island.

If the ecologists were to be believed, Manto Island was slowly disappearing, being gnawed away by high tides. But Latif never believed the ecologists, and to prove them wrong he kept a tab on the margins of his village and found the dimensions unchanged; the land had not shrunken even by an inch, the river had not grown any wider. The island appeared robust enough to outlive his generation, unless it had secret plans to collapse from the middle and let itself be sucked to the bottom of the river.

Everyone who lived on the island thought it was immeasurably big, and in that false sense of enormity Latif’s house was a long distance from Manto Road, a gruelling ten-minute walk from the pier. He lived on the other side of the island, near the marshes, at the end of an alley padded with fallen leaves and fenced by an unbroken line of quickstick plants.

Hardly a mile away from his home, the pier sat at the north end of the island: a hurriedly constructed finger of concrete that jutted out into the river like a bridge abandoned halfway through construction. A shed stood a few feet away, propped up on four pillars furiously scrawled with charcoal sketches of genitalia. The teabag-like testicles and the angry curls of pubic hair always ran a wave of suppressed laughter through Latif. A footpath worn smooth by generations of islanders going to the mainland to work, trade and philander—only to return home sombre-faced—twisted through a wooded estate and joined the street that, despite the fury unleashed on the statue, still bore the name of Manto. He had considered Manto Road to be the busiest place on earth until the day his school went on an excursion to a city, south of the archipelago, to visit a museum of archaeology. The city was so big and busy it burst the bubble of Manto Road forthwith, and Latif started to think of the urban side of his island as a mere rotogravure that belonged to the very museum he was visiting. It took him months to look again at the street with some amount of respect, and even then he did not stop lusting after the lives of the boys who lived in apartments so tall he imagined their windows to shut against moving clouds.

The night before his first day at work, Latif’s home hardly slept. His sisters took turns to iron his best clothes until their pleats turned blade-like while he, cooped up in his room, carefully employed an eyebrow pencil to darken the hint of a moustache into something that resembled a flattened centipede. By the time he went to bed, the kitchen light had already come on and his mother had started to cook lunch for him while the rest of the island was not yet contemplating breakfast.

It was still dark when he left home, escorted by his mother and sisters up to the little wooden gate. His footwear made short squeaks on the slushy alley floor and, once he turned the corner and fell out of his family’s eyeshot, it was the only sound that assured him that he was not wandering in a dream. In the empty alley he felt like a shadow without a body, one-dimensional and weightless, invisible even to the dogs that guarded the houses along the way. Roughly an hour later, he felt even more invisible as he stood in front of the collapsible door of Paradise Lodge and rapped on it apologetically for attention.

A stout man, whom he seemed to have known back from Manto Island, stared sleepily at him for several minutes through the grille before unchaining the door and letting him into a spacious lobby, lit by a single lightbulb. Latif placed a hand on his heart as if complaining of angina and mumbled his wish to meet the manager. The man plopped onto a chair and placed a little board on the countertop which read Manager. ‘Where have I seen him?’ Latif thought. His heart sank when he noticed a saffron thread on the manager’s left wrist; it somehow suggested that no matter how doggedly he worked, he would be constantly frowned upon.

‘Yes?’, the manager grunted.

In a lowered voice, Latif introduced himself as the candidate sent by the owner of Quilon Cashews. He expected the expression on the manager’s face to melt into consideration, or even kindness, but the manager merely pointed to a bench and asked him to wait. As he sat down, his back turned to an arched window, he suddenly remembered where he had met the manager, or rather why he had looked so intensely familiar. He looked like a Mexican footballer who, to judge from the yellow and red cards he kept earning, was not a nice person to know.

As the light hardened on the windows, he surveyed his new workplace with curious eyes. The false ceiling, the wooden panelling, the shape of the windows and the ornamental lampshades suggested that it had once been a premium boarding house, when the bellboys were probably liveried, and the watchmen worked in shifts. But now the walls were streaked with dirt, the furniture looked like antique pieces on sale and the ceiling fans had yellowing blades and squealed like trapped mice. Behind the counter was a single window that framed a star fruit tree. As he sat staring through the window, the tree silently dropped a fruit. He felt a boyish urge to run to the tree, pick it up and sink his teeth into the flesh the colour of Brazilian jersey. It was too early for something as sour as a star fruit, but poor sleep had turned him hungry and he felt guilty about opening the lunch pack when it was not even properly morning. His empty stomach burning with hunger, he sat still and watched the lobby limp to life.

The other bellboy was an old man who walked slowly around the lobby as if bogged down by elephantiasis, though his legs were thinner than Latif’s. Latif watched the old man fill frosted plastic jugs at the water dispenser and arrange them on a tray, open a cloth bundle and take bedsheets out, run a wet rag over the countertop and dust the fat ledger. Watching the old man was a rushed apprenticeship in housekeeping for Latif. He was to later do what the old man did now.

At the stroke of seven, a middle-aged lady walked into the lobby and, mistaking Latif for a lodger waiting to be checked in, smiled politely at him. The manager looked at the clock which, more than telling the time, hinted at the heyday of the lodge. Just when Latif thought he was about to compliment the lady for her punctuality, the manager started to shout at her for being late by half an hour. Anger made the manager look more like the footballer, and Latif took the shouting as his formal introduction to the lady; her name was Stella, her job was to sweep the front yard and mop the rooms, and she lived just three streets away. Stella paid little heed to the manager, so Latif knew this happened every morning. She went to the anteroom, and when she returned she was wearing a faded shirt over her clothes and wielding a long-handled broom. She opened the fat ledger from the backside where it doubled up as the muster roll and scrawled her signature on it, then dragged the broom past him.

‘Stella, this is the boy I was talking to you about yesterday.’ The calmness in the manager’s voice surprised Latif. ‘He will do full day shifts on alternate days. He will sleep on the bench. When you are done with sweeping, tell him what he is supposed to do.’

Stella smiled at him again. Her smile was no longer polite, if anything it was sympathetic. She went out to work her broom on the forecourt until she could gather a heap big enough to make a decent bonfire out of.

Half an hour later, Latif opened the ledger from the backside and carefully drew his signature between two blue lines. It was about an hour after he was absorbed into the rusty mechanism of the lodge that Latif found himself holding a bedsheet in one hand and knocking courteously on the door of Room No. 117, waiting for a dead guest to respond.

(This is an edited excerpt from Anees Salim’s The Bellboy, releasing on September 5, 2022)