Power of Autonomy

FOUNDED IN FEBRUARY 1881 by missionary scholars from Cambridge University, St Stephen's College is a Christian minority institution that has encouraged all who wish to excel in their studies. The college has been consistently ranked among the top educational institutions in the country for over several decades, and in the latest NAAC ranking too it has secured the top rank with an A++. This heritage institution is one of the oldest colleges in Delhi. It was one of the three constituent colleges when the University of Delhi was set up in 1922.

The primary reason why St Stephen's has consistently topped the list of colleges in India is its emphasis on hard work and excellence. Among its alumni are heads of governments, a former president of India, current and former chief ministers of several states, central and state ministers, the current chief justice of India, several judges of the Supreme Court, the current governor of the Reserve Bank of India, several sportspersons, including national awardees and Olympians, globally respected academicians, social workers, heads of corporate establishments and artists. While hard work and excellence are the prime ingredients for the success of its students, the credit for their stellar performance also goes to their single-minded focus and Mahatma Gandhi's mantra of "simple living, high thinking".

Both Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore are part of the college's history. Sushil Kumar Rudra—the fourth principal of the college and the first Indian to hold the post—is credited with encouraging Gandhiji to come from South Africa and lead the freedom movement. The friendship between CF Andrews, (whom Gandhiji fondly christened "Deenabandhu"), Gandhiji, Tagore and Rudra is legendary. It is even said that some parts of Tagore's Geetanjali was translated in the principal's residence. The institute's contributions to the freedom struggle through the efforts of Lala Har Dayal and Amir Chand are on record. It was from the campus of St Stephen's College that Gandhiji gave the clarion call for the non-cooperation movement.

Imran Khan: Pakistan’s Prisoner

27 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 60

The descent and despair of Imran Khan

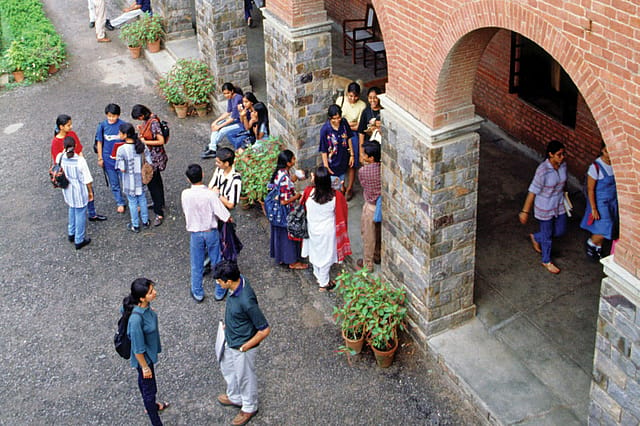

Till 2022, the college has had a pan- India student profile. This makes the institute a "mini India" and paves the way for a better understanding of the multi-ethnic cultures and languages of the country. St Stephen's has always strived to maintain the gender balance too.

Unfortunately, the Common University Entrance Test (CUET), which may have been well-intentioned, does grave injustice to the students who've put in 12 years, or more, of hard work at school level. Students have now been taught to believe that school education really doesn't matter, as long as they clear their CUET. Such a thought is like striking at the roots of a sapling. If we have global leaders today from India, an Ajaypal Banga, a Kaushik Basu or a Satya Nadella, one strong reason for their success is the educational foundation that they all received in India from an Indian educational system. Unless the National Education Policy (NEP) can come up with something better than the CUET, I fear we will lose out on the huge advantage that Indian students had so far globally, owing to their solid educational foundation at school. The mushrooming of coaching centres for CUET is another indicator of the detrimental effect of the CUET.

The CUET is not the answer to high marks. The answer perhaps lies in the realignment of the school system of education, having better teachers and evolving a system that encourages its students to come forward confidently. A practical and logical solution to different boards and high marks would have been the time-consuming but effective interview process that has worked brilliantly well at St Stephen's College for close to seven decades. To ignore the real experience of a successful process that has been in practice for over 70 years is like walking into a ditch in broad daylight even when your eyesight is perfect. The University Grants Commission (UGC) must review this poorly thought out exercise of CUET.

The NEP has been rolled out; but like many teachers and teacher-administrators know, it has been done too soon with very little planning. Numerous courses, some ill-planned, some whittled down with lesser content, and fewer hours of instruction are not going to help the students. The earlier three-year undergraduate courses had more substantial content, and what's more, our students saved a full year.

Another serious problem that the NEP has brought up is that of inadequate infrastructure. For a traditional college like St Stephen's, to suddenly be expected to have a dozen or more new classrooms, the related infrastructure and incur the expenses that come with them—furniture, equipment, lab apparatus, and qualified staff—is really asking for too much, too soon. With such short-sightedness we are doing ourselves great harm, we are short-changing our students and destroying their future.

The greatest disservice that the hurried implementation of the NEP has done is with regard to inadequately qualified and poorly trained teachers. By introducing strange recruitment policies, by discrediting research and doctoral work, the future of higher education in India does not look very bright. Earlier, education was a great stepping stone for the lower classes, a great leveller. There are several examples of those who've worked hard and come up in life turning out to be role models for others, a prime example being our much beloved and late President Abdul Kalam Azad. With the government encouraging privatisation, welcoming foreign universities and withdrawing financial support, higher education in India is staring at a very bleak future. Why can't the Education Cess, which was collected for so long across India, be used to support higher education? Where has that money gone?

The NEP is, like many teachers, academics and administrators have pointed out in numerous articles and on several fora, a well-intentioned document. However, for it to deliver, it needs detailed planning and financial backing from the government.

St Stephen's College has never shied away from being a pioneer in practical, world-class education. The institution provides education in its real sense— not limited to marks alone but churning out leaders who lead governments and institutions across the world. The establishment of the Centre for Advanced Learning (SCAL) in 2020 is only another step in yoking theory and practice for the benefit of all. The college will continue to pioneer even amid all challenges. We can't help but do this, because excellence and service are in our genes and the founding fathers proved as much.

St Stephen's College has always had its doors open for all who wish to excel. We've applied for autonomy in the spirit of enhancing excellence and we hope that it will be granted. The NEP encourages autonomy and the college has plans chalked out for the future. But we cannot move forward with our hands tied, our feet shackled and agencies restraining our desire and efforts. St Stephen's College should be granted autonomy in its truest sense within the frame of the Constitution of India, respecting the successes of the past and encouraging the college's efforts to become the proverbial light on the hill.

St Stephen's College believes in wholesome education. If you ask any alumni about their success story, their answers will help you understand why the college consistently tops the list of the best institutions in India.