Vitamin R in Tobacco Land

MARITZA, THE TRAVEL manager of the Nacional Hotel, books me on a one-day bus tour of the western part of the island nation. Never an admirer of these touristy trips, I choose this one because it is the best way to visit the country’s most famous tobacco-growing area. I have already bought three expensive single cigars from tobacco sellers that Alex the chauffeur had taken me to in Havana—one an H. Upmann Magnum 56 limited edition, a Cohiba Lanceros (which was the cheapest of the Cohiba brands I could lay my hands on in the capital city) and a Montecristo Edmundo, which is named after Edmund Dantes, the hero of the Alexandre Dumas novel The Count of Monte Cristo. All these are for a Malayali friend who is a cigar aficionado. I plan to buy more cigars for other friends when I visit the tobacco farms.

A non-smoker, I wouldn’t have taken interest in Pinar del Río had it not been for its culture and reputation for making some of the finest cigars in the world—and the realisation that cigars mean a lot for the government of Cuba. It exports cigars to most parts of the world, except the US where it cannot sell its cigars or rum or for that matter any of its homegrown products. It is an altogether different matter that Americans still manage to smoke Cuban cigars.

The American tourists I met in Cuba told me their biggest draw was cigars and rum. Many of them had booked return flights via other countries and made sure that they peeled off the packaging in case customs officers checked for Cuban goods when they landed back home.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Located more than 160 kilometres from Havana, Pinar del Río is Cuba’s western-most province and is well- known for a UNESCO world heritage site called El Valle de Viñales (Viñales Valley) and the tobacco-growing region of Vueltabajo.

On our way in a luxury Yutong bus, I notice that most of the tourists are from Canada, the Caribbean and Spain, and one each from India, the US and Japan. The American is accorded much warmth by our guide, who says she is glad to see him as part of this team, and that since it is his first visit, she will make sure he gets to speak with as many local people as possible.

It is a long drive on the A4, a six-lane motorway built with Soviet and East European assistance. The terrain, foliage and trees all around look no different from southern India except for the roads and the vehicles that we overtake. There isn’t much traffic. I merrily click photos of old, comic- looking cars, some of which are, as writer and journalist Anthony DePalma describes them, ugly hunks of battered metal, held together by wire and running on hope. Certain vehicles even remind me of improvised vehicles one sees in the villages of north India, in which a handset generator is used to fuel what appears to be a cross between a scooter and a bullock cart. As in rural India, one can see farmers seated with their perishable produce along the roads—they are mostly villagers from the Artemisa Province, which includes municipalities such as San Cristóbal and others. We meet several farmers along the route. There are also cheese farmers, those who sell homemade cheese and guava bars. A few cars stop to make purchases, though our bus doesn’t. If the driver or the guide had ordered a halt, I am sure many people on the bus would have bought cheese bars. Instead, we drive on, wondering what they must taste like.

The guide keeps making announcements in English and Spanish; she is well-versed in the history of the region. We stop midway for snacks, and I find the restaurant bar to be excellent as it caters exclusively to foreign tourists.

On reaching Pinar del Río, where 65 per cent of Cuba’s tobacco is produced, we go straight to a tobacco firm where we are welcomed by a cheerful man wearing a straw hat and clothed in fashionably torn blue jeans and a double-pocket Cuban shirt with a logo of his tobacco brand above the right pocket: Macondo, a farm where tobacco is grown using traditional methods. He holds a small plastic container in his left hand and a brochure in his right. I think I hear him say his name is Nelson, but I could be wrong. He gestures liberally with his right arm, explaining what the traditional method of tobacco farming is all about. He explains first in English and then in Spanish with tremendous flair and a sense of humour, without sounding one bit mechanical or in automation mode.

We are standing in front of a house-cum-barn behind which he will demonstrate to us how to roll tobacco leaves and make a cigar—and how to smoke it. To the left of the house, there stands a barn with thatch roofing made of hay (the house bears a stark resemblance to old homes in Kerala and some parts of India that have thatch roofing using hay and dry vegetation; in Kerala, besides straw, we also use palm leaves and water reeds).

Inside the barn, processed tobacco leaves are hung to dry. Once dried, the leaves are typically cured in a special concoction that includes guava leaf, honey and rum mixed into water, a practice that requires great mastery.

I feel as though I am in a Kerala countryside, rich with palms and banana trees and houses made with hay and reed roofs. In the distance are a few buffaloes feeding on grass, and pigs foraging peacefully. The place is lush green and relatively desolate.

After exchanging pleasantries and asking each one of us to introduce ourselves, Nelson seats himself at a high table of sorts, with photographs of Fidel, Che and Camillo puffing at cigars behind him. Also on display are a flag of Cuba, a lantern, and a calendar-shaped figure of the tobacco plant detailing various parts, making it look like a botany lab.

We are served black coffee immediately and Nelson stands for a while behind the handless chair as if he is going to give a speech. He is a natural—confident and full of life. He speaks eloquently, switching between English and Spanish with the skill of a matador in a bullfight.

Then he sits down. On the table in front of him, there is a board to roll tobacco. A vial of honey is placed next to it. So are a few cutting tools, which he touches like a surgeon checking his equipment before an operation.

We are getting into the most important part—how to roll a cigar.

“The first thing you have to do (he translates this into Spanish, too) is to remove the midrib of the leaf,” he says and does so without even appearing to do it. I see the midrib only when he flaunts it. The leaf appears untouched and unaffected by what he has done: this, for sure, is the equivalent, from the leaf’s viewpoint, of a massive laminectomy. But it looks as it was before. This is getting entertaining and that is exactly what our host intends.

“According to various studies and statistics, 99 per cent of the nicotine is concentrated here,” he says, brandishing the midrib. “Have you heard that cigars are less addictive than cigarettes? One of the reasons is this one,” he asserts, referring to the removal of the midrib.

Our man demonstrates his rolling skills along with his bilingual deftness.

“Another reason is that we don’t inhale the smoke,” he says, contorting his face to give the expression that it is taboo to inhale smoke while enjoying your cigar.

Then he explains how to smoke the cigar. You roll the smoke inside your mouth, take in its flavour and exhale.

“Smoking a cigar is like drinking wine partly because of the wine you drink,” he avers, suggesting that he is referring to the fun of it, in a literal sense.

He wipes his forehead with a handkerchief that looks tiny for his face.

Then he dwells on what happens to the midribs, or as he calls it, the veins. “We don’t throw them away. We put them in water for some fifty or sixty days. The water gives out a strong smell and we spray it in the tobacco fields. It is to protect the plants against the caterpillar, which loves to eat the leaves.”

He then goes on to remove veins from two more leaves and then starts rolling the cigar.

“What am I doing here?” he asks like a teacher does with school kids. “Tell me, what am I doing here?” he repeats himself, in English and Spanish.

Someone mumbles inaudibly. “Sorry,” he says loudly. “But what am I doing with the leaves?” he asks again, this time in a harsher tone, rolling his sleeves. One of the guests gets up and sits close to him.

“Yes, you said it,” he tells a lady at the back. “You are right, I am mixing the leaves. You are right. I am blending,” he says, stressing the blend part. BLAANDing, yes, he says.

“The second part is binding. Holding them together.” I try to imitate him with my own set of leaves but fail.

“We roll the cigar with the middle leaves of a plant— which are the best for rolling. Then you have to massage the cigar to shape,” he offers, adding that if you know how to massage you can roll a cigar. “That is why they say the wives of those who roll cigars are always happy,” he chuckles.

Then comes the cutting part. He applies a little bit of honey to make the roll stick tighter. “This works differently with machines, but we don’t use them.”

The cigar is ready for use.

He offers a handful of cigars to the guests. A few people accept them and imitate him—the way the cigar is lit and smoked without inhaling. “If you want, you can dip the cigar in honey and light it, for flavour,” says Nelson.

Now it is time for sale.

Details about the ‘draw’ and quality of organic tobacco are discussed. I buy two. He packs them for me with great care. There are many more buyers.

I HAD ONCE READ about the interesting link between tobacco and reading habits—a story true of Kerala too. For my Master’s thesis, I examined how a Marxist newspaper played a role in the dissemination of information among beedi workers in Kerala. My paper was set in 1990s Kannur, my hometown, when the rolling of beedis—thin cigarettes made with beedi leaves—offered a route out of poverty for hundreds of otherwise unskilled labourers. I zoomed in on Kerala Dinesh Beedi, a cooperative run by thousands of workers and a Marxist bastion, which has now diversified into food processing, textiles, and so on.

Back then, as the workers slogged at such beedi-rolling enterprises, they typically hired young students— or someone literate enough—to read newspapers aloud to keep them all abreast of the news. The reader’s reward would be a packet of beedi and a cup of tea. If the reader was a beedi worker, others, both men and women, would contribute a share of their rolled beedis to ensure that he or she met the day’s work target. I have come across beedi units where they got readers to read aloud novels and other books, ranging from those by politicians of the stature of EMS Namboodiripad and novelists such as French icon Albert Camus and Mexico’s Juan Rulfo (all in Malayalam translation). Many beedi workers later became political leaders in Kerala’s communist parties.

In Cuba, too, a similar practice is deeply entrenched among cigar rollers. They have very professional readers who read books for the employees of cigar factories. It is a well-documented aspect of Cuban cigar factories, and a practice that has been in place since 1865, when workers at the El Fígaro factory in Havana picked a colleague to read to them as they rolled. The reader was promised more cigars to compensate for his missing hours. Later, the others chipped in to pay the reader a salary. Despite initial resistance from factory owners, the practice spread. It is said that independence hero José Martí himself once sat in the reader’s chair to deliver a speech to emigrant Cuban tobacco rollers working at a factory in Florida. The Cuban government has declared the readers’ job a “cultural patrimony of the nation”.

Interestingly, both in Cuba and Kerala, where communist parties hold great sway in the cultural space, the quest for political literacy appears insatiable, especially among the working classes.

For Cuba, tobacco is one of its main sources of export revenue. The country sold tobacco worth $568 million in 2021, which was 15 per cent more than a year earlier. The Cuban government procures 90 per cent of all farmers’ produce and pays a ‘set price’ for it. The farmers are usually able to turn a profit, but sanctions have hurt them, too, especially in years when supplies of fertilisers and pesticides are low.

Incidentally, in 2022, Cuba won a twenty-five-year-old legal tussle over US trademark rights to its famed Cohiba cigars. State-owned Tabacuba, or Grupo Empresarial de Tabaco de Cuba (Union of Tobacco Companies of Cuba), is the dominant cigarette manufacturer in Cuba and a 100 per cent state-owned entity. It has collaborations outside the country through its ventures. The irony is that although Cuba has the right over its cigar brands, including Cohiba in the US, it cannot sell them there because of the embargo. “They hate everything made in Cuba, especially in Miami,” an official had forewarned me before I returned to India via the US and Canada. I didn’t take it seriously and paid a price for it.

We are now headed to Viñales Valley through the typical tourist route every visitor to this part of Cuba takes. I go through the usual aspects of a touristy outing: lunch, lunchtime drinks, and a visit to the La Cueva del Indio (Indian Cave), which has an underground lake where you roam around in a boat. I feel good and mobile here because I had skipped Vitamin R (that is what they call rum) and had plain, non-alcoholic Piña Colada, not one, but two.

Here, after many days, I miss my family back home. They would have enjoyed this. It is a holiday tailor-made for families. I also miss my trekking friends in Sikkim, in India’s Northeast, who would have loved the chance to hike in the beautiful mountains here.

But then, I am on my own and I will do it the way I please. Tonight, I will honour my instant friend Enrique and stay back on the lawns of the Nacional de Cuba Hotel and eat at the Cuba restaurant, which serves some mouth-watering items, including cassava (similar to Kerala’s very own kappa, or tapioca, which goes with any meat dish); Ropa Vieja (shredded beef) and Moros y Cristianos (Cuban version of rice and beans).

Long before we return to Havana, I am already there in my mind. The lone Japanese girl on the bus, who had travelled to Cuba from Bogotá, Colombia, where she is a student of Spanish at Bogotá University, is keen to speak about her holiday in Rajasthan, western India. She is in her early twenties and has already travelled half of the world. I engage her in conversation for a while, but soon I become distracted for no special reason other than an overwhelming desire to reach Havana and crash in my bed. It isn’t a pleasant feeling but the only thing that makes me feel good is the new stock of Maconda cigars from Pinar del Río, and Guantanamera cigars (along with a cigar cutter) that I picked up from a souvenir store at the Mural de la Prehistoria (prehistoric mural) on the wall of the Pita mogote (hill) in Sierra de los Órganos, four kilometres west of the Viñales town. This mural, completed in 1964 and considered the largest in the world, is a tribute to the first inhabitants of the Cuban archipelago and is one of the most visited tourist spots in Cuba.

When the bus finally drops me at Hotel Nacional, I feel bad about disappointing the curious Japanese girl studying Spanish in Bogotá by going silent midway through our conversation. But I am too tired to feel a sense of guilt. I tip the guide—who smiles back heartily—and dart into the hotel lobby, taking long strides towards the early twentieth- century room-sized lift of the heritage building to my room. As it always happens, long bus trips make me sick. My stomach has expanded. I feel uneasy. I want to clean up and rest and, so long as I can stay awake, re-watch Sara Gómez’s De Cierta Manera on Mubi (by fast-forwarding it for scenes that, I believe, offer newer insights about Cuba).

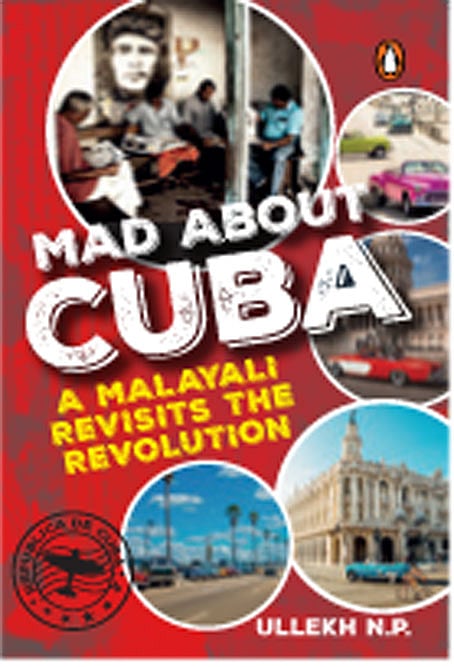

(This is an edited excerpt from the forthcoming book Mad About Cuba by Ullekh NP)