The Cult of the Angry Young Man

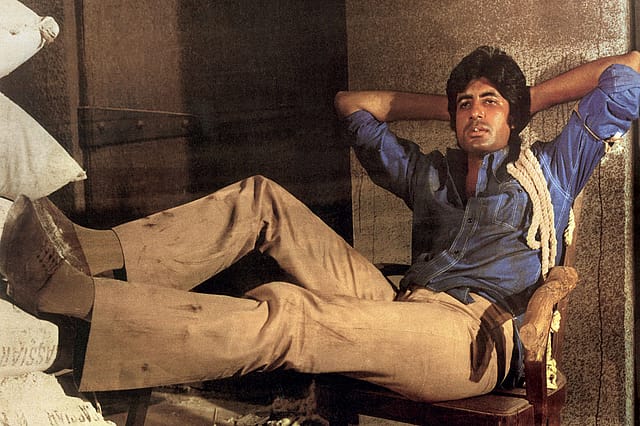

AMITABH BACHCHAN turns 80 on October 11, 2022. Not surprisingly, there is a clamour to look back at what has clearly been a stellar career with many remarkable highs and some significant lows. As the most active actor and star of his generation, Bachchan has continued to be a major media personality even today. His journey with cinema has remained dynamic since he kept reinventing himself to suit the demands and challenges of technological transformations that started in the 1990s. Bachchan is an active social media user, a popular host of the reality show Kaun Banega Crorepati, a character actor in a number of films, and holds on to a legacy that continues to grow, with many actors citing his 1970s and 1980s persona as a pivotal moment in influencing their own work and desire to become actors. With the Bachchan persona of that time, Bombay cinema expanded its ubiquitous presence in everyday life; his posters and billboards carried a new facial physiognomy of anger and an action-oriented body language available in a host of posters of films like Zanjeer, Deewaar, Trishul, Kaala Patthar, Don and Kaalia, among others. It was hard to miss Bachchan's larger-than-life presence as audiences lined up outside theatres to experience the magic of this lanky star.

However, the weight and transformative media context of the last 25 years appear to have overshadowed Bachchan's iconic role as the rebellious "angry man" in films written by the writer duo—Salim Khan and Javed Akhtar. For many people today, Amitabh Bachchan is the friendly host on KBC, a man who endorses a variety of products for television and print media, some of which have been controversial (such as the one for Gujarat tourism), and someone they see in films alongside other contemporary stars. To them, Bachchan is not the action-oriented, smouldering persona whose meteoric rise to super stardom is still considered a miracle of sorts.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

In 1995, Bachchan received a hefty fee for a television endorsement campaign for the then powerful electronics company, BPL (British Physical Laboratories). The actor had taken a break from cinema since 1992 but had signed the deal with BPL in 1995. The television campaign was innovative and drew on the actor's performances in his best-known "angry young man" movies of the 1970s and '80s. "Believe in the best", declared BPL's popular tagline. The commercials were aired on television just before Bachchan's return to acting in 1997 and they had a significant impact. The BPL campaign made two things clear: That the actor was still relevant despite his age and break from acting, and that celebrity endorsements would play a huge role in redefining the terms of stardom in the years to come. While the memory attached to the legacy of the actor's performances was still powerful in the mid-1990s, successfully invoked by the BPL advertisement campaign, the situation is quite different today since in the last three decades, Bachchan has created an entirely different persona for himself.

It is therefore important that we return to the decades that led to the rise of Amitabh Bachchan. What is it about that moment in the 1970s and '80s that requires us to engage with it? How do we make sense of the context and the persona that reigned supreme in that period? Let us begin first with an assessment of the actor's particular talents. Amitabh Bachchan's performances during the heyday of his career were marked by an ability to convey a smouldering sense of inner turmoil, a body coiled in angry knots waiting to explode on screen, a form of dialogue delivery that no one had seen until his arrival on the scene, and a star persona built on height, posture, restraint, and tremendous skills with action. The tag "complete actor" was commonly deployed in industry conversations to describe Bachchan's virtuosity. Essentially, this phrase described the actor's aptitude for comedy, action, dance, drama, and romance. The development of the "one-man performer" who could handle everything on his own gradually led to the marginalisation of comedians and other side characters who had previously offered comic relief in the background of the main plot. As we all know, Amitabh Bachchan's dynamic performances allowed him to effortlessly switch between brooding rage, humour, romance, and action.

Bachchan's fame also came at a time when action in the business was becoming increasingly professional. Many action directors took note of the actor's ability to perform his own stunts. "Show me one actor anywhere in the world who can execute the kind of feats Amitabh does without a double, and I'll give you my right arm," remarked MB Shetty, who had concurrently become the industry's most highly rated stunt director. Bachchan's success with stunts was widely covered by the popular press and made a significant contribution to the development of his masculinity. The limited but well-known dance moves that Bachchan used in some of his films came to be recognised as his signature step. Most importantly, as Bachchan rose to become the highest paid actor, the female leads became less significant. Therefore, the concept of the "complete actor" suggested a massive concentration of industrial activities around a single individual. Bachchan was described as a "one-man enterprise", and his inclusion helped to sell the movies. The actor was rumoured to occasionally switch between different projects that were all being shot on the same day.

As the "angry man", Bachchan was thrust into a cinematic imagination of political and social unrest by the talented writing team of Salim-Javed. It was in the 1970s that the government's slogan, "Garibi Hatao (Eradicate Poverty)", rang hollow given the daily experiences of inflation, rising unemployment, and widespread political and financial corruption. The government had also displayed a remarkable indifference to the upsurge of student movements across the country, raising issues concerning the youth. It was this sense of helplessness that sparked a bitter rage, which Bachchan channelled on screen to show how the weaker and less affluent could fight back. Thus, Bachchan cannot be seen in isolation from an India in the grip of political turbulence, marked by various events of the 1970s and 1980s. Salim and Javed were clearly products of their time, converting the emotional contours of a disenfranchised and angry multitude into action-oriented scripts and dialogues with an anti-hero at the helm of affairs. The "angry man" persona was a conscious reframing of masculinity, stardom, and political discourse on screen that impacted everything that came later.

ALL THIS STARTED with Prakash Mehra's Zanjeer (1973), where Bachchan played a police officer who turns into a vigilante and crosses over to the other side of the law. This film accidentally fell into Bachchan's lap after three other actors had rejected it. Bachchan, a struggling actor who apparently did not seem to have the attributes of a typical Hindi film hero, was the fourth choice. Once cast in Zanjeer, the actor brought his own brooding and yet explosive quality of rage to the screen, forever altering the vision of masculinity that had previously been on display. Yash Chopra's hugely successful Deewaar (1975) created a wedge at the heart of the family where the mother is forced to choose between her two sons. While Ravi (Shashi Kapoor) represents the values of the state, Vijay (Bachchan) is positioned as the outlaw figure, carrying the memory of trauma inscribed on his body. The line "mera baap chor hain [My father is a thief]," tattooed on his forearm by angry workers who decided to punish him for what they were led to believe was a betrayal by his trade unionist father, was not only a remarkable narrative device, it was also the site of deep wounds whose presence in the film only added to Bachchan's brooding persona. In Deewaar, with his larger-than-life presence and action-oriented performance, Bachchan mastered the template for the angry, rebellious figure, ready to take on anyone. Yet Deewaar also sets up a political context of the 1970s within which the angry man was positioned as a figure who experiences, remembers, and carries a past of deprivation that affects his psychological make-up.

The spatial map of Deewaar showcased the Bombay dockyards, the city's underpasses, the streets for the homeless, real estate ventures, and affluent hotels and nightclubs. These sites were considered crucial for the way Bachchan negotiated his identity in the city. In Kaala Patthar (1979), Bachchan's Vijay is haunted by the fact that he abandoned a ship as a captain when a storm made the lives of the passengers precarious. Having lost his job after a court martial and unable to deal with the humiliation, Vijay begins work at a coal mine to help him deal with his own weakness. The film was inspired by the Chasnala coal mining disaster of December 1975 and provided a detailed sense of the conditions inside the mines and the experiences of the workers. The mise-en-scène of workers' lives was important here, presented through their toil and sweat and their demands for a safer working environment. Kaalia (1981) created a revenge narrative presenting the transformation of an innocent and somewhat foolish young man named Kallu, who turns into Kaalia to avenge the death of his brother, a trade union leader. The working class subject is present in all these films because the writers saw this as the pulse of the country, a mass audience ready to identify with utopian resolutions to deep social conflicts posed in the Bachchan films. In this journey from Zanjeer to becoming a physically powerful vigilante figure, the angry man was made to speak on behalf of a teeming multitude—real or imagined.

There was something about the time, a period that also saw brooding anger and traumatic experiences in Bachchan's other films. In Abhimaan (1973), he delivered a remarkable performance as a successful singer, Subir, who is unable to handle his wife's (Uma) greater talent and meteoric rise as a singer. In Mili (1975), the hero's reclusive persona is built on the trauma of a difficult childhood with his mother. Having fallen in love with Mili (Jaya Bhaduri), a spirited woman, Bachchan is forced to experience loss again when Mili succumbs to cancer. In Kabhi Kabhie (1976), Bachchan plays the role of a poet, Amit, in love with Pooja (Rakhee). But they are unable to have a future together because of parental pressures resulting in Amit's marriage to Anjali (Waheeda Rehman), while Pooja marries Vijay (Shashi Kapoor). The main part of the film is set in the future, with complications arising from the romantic entanglements among the next generation of children. In this multi-starrer film, there was some anxiety about how audiences would deal with Bachchan as a romantic poet. The film, however, was a huge success, and even as a poet, Bachchan shouldered his brooding interiority with an outstanding performance.

In all this discussion of the angry man, we, however, cannot forget Bachchan's diverse comic roles. In Amar Akbar Anthony (1978), he played the role of a Christian bootlegger with some of the most influential dialogues written especially for Bachchan. In Coolie (1983), the actor played the role of a Muslim porter whose death, originally part of the script, was changed after his near-fatal accident during the shooting of an action sequence on the sets.

This hero with a complex psychological persona belonged to a specific historical context when the country was not just going through political turbulence; there was a felt need for a sense of hope that could capture the experiences of the swelling crowds demanding their right to land, employment, education, and a future. Here was a moment when the box-office performance of the Bachchan films was linked to the audience's desire to see rebelliousness on screen. Film history is often a collation of many such "chance occurrences" where a confluence of forces prevents us from drawing out any single causal explanation. Amitabh Bachchan's persona in the 1970s and 1980s was the result of such a combination: the remarkable talent of the actor, the politically charged and skilled writing of Salim-Javed, and a social context where anger became identified with the experiences of the disenfranchised and the dispossessed.

Also Read

Amitabh Bachchan: Legend and Legacy ~ by MJ Akbar

A Star for Everyone Anytime ~ by Kaveree Bamzai

Role Moral ~ by Rachel Dwyer

Love, Loss and Longing ~ by Kaveree Bamzai

My Amitabh Moments ~ by Kaveree Bamzai