Matinee Monsters

WE'RE SEEING A PROFUSION OF pitches," says a studio executive in Mumbai. "I am assuming some will get made." He's talking of one of the biggest trends of 2024, horror comedies. The Mumbai film industry likes nothing more than trying to replicate success, so it is no surprise that a big shift we will see in 2025 is horror stories that are part of regional folklore.

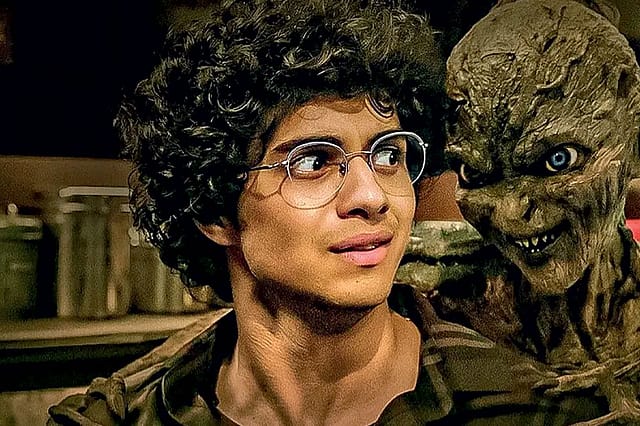

Filmmakers are tugging at their cultural roots and developing stories based around yarns they may have heard from their grandmothers of spirits, monsters and ghosts. So, if Munjya, one of 2024's biggest sleeper hits, developed a Konkani folk tale about a tree dwelling evil spirit who was denied the love of his life, then in 2025, Thama, by the same director Aditya Sarpotdar, will have a contemporary historian uncovering a legend of vampires in the Vijayanagar empire. Bhediya 2 will see the return of Arunachal Pradesh's Yapum, a shape-shifting werewolf who wants to protect the jungle, even if he must kill somebody. There will be a prequel to Kantara, the supernatural stunner of 2023; another time-shifting reincarnation drama The Raja Saab, with Prabhas; and work has already begun on a sequel to Tumbbad (2018), with its forever hungry, womb-dwelling ghost, Hastar. It was re-released successfully in theatres this year.

Once the preserve of B-Movie kings, the Ramsay Brothers, horror with a touch of the comic, have come front and centre of the cultural moment. The Ramsay Brothers were seven sons of radio manufacturer FU Ramsay, who made horror movies between the late 1970s and early 1990s. According to film scholar Valentina Vitali, these films allowed audiences to mediate the turbulent 1980s.

Indeed, horror stands at the intersection of our dreams and nightmares, telling us what is possible, even if it is not permissible. In Stree 2, it allowed the filmmakers to imagine a universe, Chanderi, in which women walked with absolute freedom while the men moped at home. In Munjya, it enabled a timid young man to intimidate his love rival (in a roundabout way), and in Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3, it gave peace to the spirit of a cross-dressing prince.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

As the opening statement in Munjya says, quoting author Neil Gaiman, fairy tales are more than true, not because they tell us that dragons exist but

because they tell us they can be beaten. In this time of anxiety and crisis, horror movies with a light touch give us hope that a better world is achievable. It is a place where a man and woman can come together and save the women of Chanderi in Stree 2; where a diabolical uncle symbolising the evil of patriarchy can be turned into a tree in Munjya; and where two sisters who wronged their brother can finally understand him and forgive themselves in Bhool Bhulaiyaa 3.

Horror films, says Sarpotdar, are just taking off in India. "The question is why didn't we make them 25 years ago? I remember Ram Gopal Varma managed to direct or produce horror movies like Raat (1992), Bhoot (2003), Darna Mana Hai (2003) and Vaastu Shastra (2004). Mukesh Bhatt did some pulpy horror movies. But no one really did it well. The last horror comedy movie that was good was Bhool Bhulaiyaa in 2007, one of the first of its kind in Hindi cinema," says Sarpotdar. "The audience which in their 20s or teens has no reference point for horror," he adds. "This audience was watching Western and Korean horror, and has now shifted to watching Indian equivalents." It is a long-term audience, which will stay true to the genre, he says.

Then there is the joy of the monsters and spirits from one movie meeting those from another in the multiverses and franchises that are being built. They not only whet curiosity but also ensure repeat viewing, when Bhediya enters the Stree universe and vice versa. For a generation that cut its teeth on superhero franchises where Easter eggs are de rigueur, this is a bonus.

Horror films are theatrical experiences, he notes, and need an enclosed space with great sound and larger than life visuals. The films that are dealing with stories out of the box, traditional folklore, and age-old rituals are doing well. A new crop of filmmakers, either trained in regional cinema like Sarpotdar, or from diverse backgrounds like director Amar Kaushik of Stree and Bhediya, are bringing their own experiences to crafting stories. Sarpotdar comes from a family of Marathi filmmakers and made the zombie comedy Zombivli (2022) in Marathi before helming Munjya. Kaushik, for instance, is the son of a forest officer. His first film, a short called Aaba (2017), was based on the Apatani tribe of the area. Bhediya, too, was filmed in the pine forests around Ziro, home to the Apatani, and cast many actors from in and around the area.

HORROR MOVIES ARE fictional, but the emotions they unleash are real. A science called neurocinema is dedicated to the study of movies on our brains. Horror or violent movies help us manage our own fears and neuroses.

It is not new for Mumbai cinema to follow in the footsteps of those who have succeeded before but there is a pure economic reason for it. Budgets are shrinking because theatrical footfalls are falling. From January to October 2024, box office collections dropped 7 per cent year-on-year. In 2023, India's annual footfall for cinema halls was around 900 million, which is far below the pre-pandemic high of 1.4 billion. Major producers are either struggling to pay their dues, like Vashu Bhagnani's Pooja Entertainment, or have chosen to sell part of their stake to carry on, like Karan Johar's Dharma Productions which sold 50 per cent of its company to Adar Poonawalla's Serene Productions.

Star costs are becoming unviable, with actors such as Akshay Kumar delivering a series of flops, most resoundingly Bade Miyan Chote Miyan, which cost ₹350 crore to make and delivered a mere ₹102 crore at the box office. Streaming platforms have tightened their budgets as well, with some mergers such as Disney Hotstar and JioCinema and disappearances such as Voot. Hindi cinema which in 2023 had got used to being subsidised by lavish production budgets from streaming platforms can no longer expect that.

If it's not horror comedies, it is big budget spectacles, usually part of a franchise, that are getting made. But since spectacles need big stars, bigger budgets, horror comedies are an easy bet. For the rest, there are sequels, from Border 2 to the Housefull franchise, covering the 1990s to now. The fewer big releases and high-ticket prices have also meant a strategy of re-releases, which has stoked nostalgia among the old and curiosity among the young.

Live entertainment will rise further, driven by FOMO and the need to boast on social media. This is curtailed by the country's lack of infra, which will struggle to catch up. On video, more time will be spent on short-form video and less time on long form. This may well see a re-invention in long form, which will come with generative AI and younger filmmakers who will understand the voyeuristic language of short-form video and translate that into long form.

But given that it takes 18 months for a film to go to market we will see a proliferation of horror in times to come. This may be overkill and cause fatigue. Given the high-ticket prices and multiplicity of options, the theatrical experience has to be value for money. Horror, despite the use of CGI, delivers it in spades since it doesn't need pricey actors.

Horror comedy, in particular, argues scholar Mithuraaj Dhusiya, creates spaces for the depiction of non-normative sexualities, critiques of feudalism, abuse of power in state organisations and rapid conversion of heritage properties into commercial malls. The horror comedy uses humour to mask the disorientation of the body even though the protagonists are misfits in their own way and prone to debilitating kinds of othering. Most of the central characters in the films are marginal, whether it is the "ladies tailor" of Stree, the male hairdresser of Munjya, or the small time road contractor of Bhediya, or even the child bride turned witch from 200 years ago in Anvita Dutt's Bulbbul (2020, Netflix).

The genre introduces us to characters we would not see otherwise. The year that has gone by has already ensured that people embraced novelty. 2024 was a banner year for women's stories such as All We Imagine As Light, Laapataa Ladies, and Girls Will Be Girls. But director Ruchi Narain feels the golden period for women's stories is over. "The recent adjustment with OTT content and budgets has shown that the viewership on platforms is overwhelmingly male. Theatrical releases also have had success with male-oriented stories, so I think that is the general direction of content now. Women's stories will continue to be made, by the passionate and brave who are desperate to share those particular stories and some will work critically and even commercially. But those will be the exceptions, not the rule." Indeed, as she points out, All We Imagine As Light was made with international funding. Films like that rarely get funded in India.

The rise of horror movies also allows us an escape from the venality that exists around us. With so many actual monsters lurking in society, from domestic predators to corrupt honchos, it is simpler to imagine wickedness as something that can be torched, extinguished, or cured through black magic. It feeds into bedtime stories we heard from parents, or myths we were told by our grandparents. The idea of watching it as a collective, sharing our deepest fears and darkest visions, sends a thrill as well as a chill down our spine. And who can deny there is something almost pleasurable in that?

Our increasingly atomised pleasures pale in comparison with the alternative of a space where everyone is collectively scared out of their wits or falling off their chairs in laughter. And if it is a mix of both emotions, in the age of high-ticket prices and even pricier popcorn, it is money well spent.