Long Shadows of the Past

WAVES OF RUSSIAN missile attacks and indiscriminate aerial bombing of Ukraine hark back to the original debate on the choice between precision-bombing of military, industrial, and political targets and the carpet-bombing of cities. World War II may not have ended as it did without the fire-bombing of German and Japanese cities. But the imperative of making Nazi Germany and imperial Japan surrender by breaking the morale of the people didn't preclude disagreement about the morality of largescale civilian casualties.

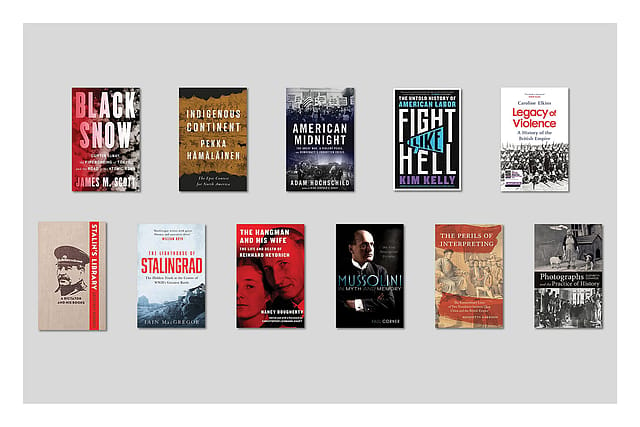

James M Scott's Black Snow: Curtis LeMay, the Firebombing of Tokyo, and the Road to the Atomic Bomb (WW Norton) goes to the heart of the matter in its portrayal of the most destructive air campaign in history. The firestorm ignited in Tokyo by 300 B-29s on the night of March 9-10, 1945 killed more than 100,000 people. Scott deftly navigates through the build-up, bringing to life personalities like Major General Curtis LeMay, Henry "Hap" Arnold, then commander of the US Army Air Forces, Brigadier General Haywood Hansell Jr, et al. First-person accounts and previously unpublished archival research make this a first-rate war history, underscoring America's moment of choice: away from daylight precision-bombing to night-time incendiary-bombing. The British had already done that to German cities but the American decision would lead to Hiroshima.

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

On the subject of America, one is tempted to stick one's neck out and say that the most impactful book of the year is Finnish scholar Pekka Hämäläinen's Indigenous Continent: The Epic Contest for North America (Liveright). Hämäläinen overturns not one but two grand narratives: white-settler America with Native Americans erased from the map and the accepted story of the indigenous peoples as mere victims. Covering four centuries, Hämäläinen argues that Native Americans had a big role to play—with agency—in shaping history. They didn't always lose battles and had continued to dominate the continent long after the Europeans came, peaking with the Lakota victory at Little Bighorn in 1876. To understand this "indigenous" continent, we would need to redraw the maps to see that the colonial grip on America was nowhere as complete as claimed.

Historian Adam Hochschild's American Midnight: The Great War, a Violent Peace, and Democracy's Forgotten Crisis (Mariner) is a close contender for book of the year. Between the end of World War I and the Roaring Twenties, America was in crisis. In its darkest hour, a pandemic, violent racial battles, an intolerant justice system, censorship and political repression, mob lynchings—a near-total collapse of the rule of law—had brought the US to the brink. Hochschild's masterfully crafted story of a forgotten half-decade that almost destroyed American democracy is an important work irrespective of the times.

Another notable book on America this year is journalist Kim Kelly's Fight Like Hell: The Untold History of American Labor (Simon & Schuster), impressive not only in its range— from southern freed Black women organising to protect themselves to the civil rights movement, from the plight of Jewish immigrant workers' to Asian indentured labour or the fightback from LGBTQIA people—but also in naming the forgotten dead who showed great courage to secure a little dignity and a semblance of freedom.

Caroline Elkins' much praised Legacy of Violence: A History of the British Empire (Bodley Head) is a good book flawed by its neglect of Indian (and perhaps by extension all 'native') scholarship, as pointed out by Rudrangshu Mukherjee. Elkins had done Kenya yeoman service when her research had unmasked the violent suppression of the Mau Mau movement of the 1950s. Her Britain's Gulag (2005), dismissed as an exaggeration, was vindicated when the "Hanslope cache" of 240,000 top-secret files was discovered. Britain had to pay reparations to more than 5,000 surviving Kenyans.

Talking about legacies of violence, Geoffrey Roberts' Stalin's Library: A Dictator and His Books (Yale University Press) is 270-odd pages of fascinating reading. Stalin was an avid reader but that's one part of the story. The other is what he read and what he made of it. Stalin's marginalia is legendary and could range from enthusiastic agreement to dismissive abuse. His dedicated library and his growing paranoia about his 'librarians'—he feared they could lace the pages with poison—all find their way into this extensively researched book from the biographer of General Zhukov.

Iain MacGregor in The Lighthouse of Stalingrad (Constable) takes us to the "Hidden Truth at the Heart of the Greatest Battle of World War II" as the subtitle claims. "Pavlov's House", codenamed the "Lighthouse", was a strategic building on the Stalingrad frontline. MacGregor, with in-depth archival work and hitherto unpublished accounts of German and Russian soldiers, builds outwards from the core story of a few Red Army soldiers holding out against the Wehrmacht's 6th Army and opens up one of the Soviet Union's (and the war's) biggest legends to a more exacting examination to arrive at the 'truth'.

Nancy Dougherty died in 2013 but her The Hangman and His Wife: The Life and Death of Reinhard Heydrich (Knopf), which came out this year edited with a foreword by Christopher Lehmann-Haupt, gives the lie to the idea that there was nothing left to say about one of the most inhuman individuals of the 20th century—Reinhard Heydrich, the "Butcher of Prague", Reichsprotektor of Bohemia and Moravia, and one of the chief architects of the Holocaust. The book explores how this barbaric human who loved chamber music, Hitler's "man with an iron heart" who never quite outpaced the rumour of his quarter-Jewish blood, became who he was, against the backdrop of his wife Lina's—the original Nazi of the pair—voice.

Paul Corner's Mussolini in Myth and Memory (Oxford) is another timely work that punctures the slow decades-long popular rehabilitation in Italy of the first totalitarian dictator, demonstrating why the desire for strongmen leaders is a bigger danger facing Western democracies today, more than the crisis of democratic leadership itself.

Henrietta Harrison's The Perils of Interpreting: The Extraordinary Lives of Two Translators between Qing China and the British Empire (Princeton University Press) came out at the very end of last year and thus deserves a mention here. Harrison takes the fates of Li Zibiao and George Thomas Staunton, two interpreters attached to the Macartney embassy to the Qianlong emperor in 1793, and turns their story into a penetrating new study of how China's relations with the West (that is, Britain) developed, what went wrong, how, and why—why the very act of translating and working as a go-between meant Li was later hunted in a climate of growing mistrust that ended up costing China dearly.

Elizabeth Edwards' Photographs and the Practice of History: A Short Primer (Bloomsbury Academic) is technically a 'textbook'. Edwards is not concerned with "how to use photographs as historical sources" or theories of history. Instead, she focuses on "the intersection of photographs with a series of values and assumptions that underpin the practice of history", enquiring "what photographs might do to how we go about our historical business." There aren't, in fact, too many photos in the book but each one selected is meant to illustrate a point. Written in an essayistic form rather than as a dense academic volume, this is a book anyone interested in that "intersection" can enjoy.