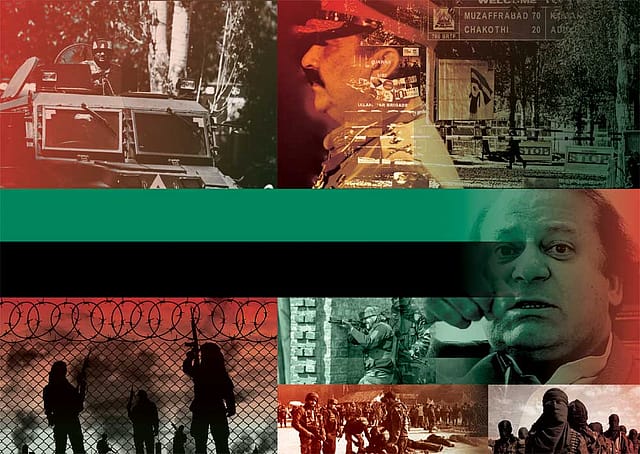

Denying Pakistan the Dividends of Terror

Since the earliest months of its existence, Pakistan has sought to seize Kashmir through the use of state proxies. That first dalliance with so-called 'irregulars' as tools of statecraft led to the first war between India and Pakistan in 1947-48. In its endless zeal to appropriate Kashmir through warfare, it again started—and lost—wars in 1965 and 1999. Since 1989 it has cultivated a proxy war, of varying intensity over time, in Kashmir. The Pakistan army's untiring enthusiasm for backing terrorist groups that enthusiastically kill Kashmiris for the army's aims demonstrates that Pakistan has little regard for Kashmiris themselves whose land it covets.

In recent decades, some of Pakistan's less-disciplined proxies have turned their weapons against the state and its polity. This blowback has claimed the lives of tens of thousands of ordinary Pakistanis, many of whom are children. Yet despite the outcry in the aftermath of the bombing of the army school in Peshawar and talk of Pakistan's 'strategic shift', Pakistan remains undeterred—and even evermore resolute—in its addiction to so-called 'jihad' to achieve its foreign policy objectives in India, as well as Afghanistan.

Why does the Pakistan army continue to rely upon a tool that has brought great harm and international calumny to the Pakistani state? The answer is as simple as it is cruel: Pakistan's army uses terrorism, under the safety of its ever-expanding nuclear umbrella, because it works, is cost-effective, and offers putatively plausible deniability because Pakistan's own security forces are not engaged in the butchery. More appalling yet, Pakistan's deep state is indifferent to the deaths of its citizens as long as some of these groups are still willing to do its malevolent bidding in India and Afghanistan.

Iran After the Imam

06 Mar 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 61

Dispatches from a Middle East on fire

The most recent outrage at Uri was surely an attempt by Pakistan's army to punish India for Prime Minister Narendra Modi's widely-praised Independence Day speech in which he raised the khakis' hackles by dilating upon Pakistan's extensive human rights violations in Balochistan. Modi's efforts to focus domestic and global attention to Pakistan's sinister malfeasance in Balochistan was likely a riposte to Pakistan's instigation, and subsequent exploitation, of the current crisis in Kashmir precipitated by the killing of a known Pakistan-backed terrorist commander, Burhan Wani. Wani was associated with the Hizb-ul-Mujahideen, which the United States, European Union and India have designated as a terrorist organisation. Pakistan's civilian-led government decried his killing by Indian security forces as 'deplorable and condemnable' in yet another spectacle of Pakistan's wantonly indefatigable support of terrorism.

We have seen Pakistan rejoin words with carnage before: in the summer of 2015, Pakistan responded to the Modi Government's bluster after the so-called Myanmar raid with the attack on Gurdaspur, Punjab. Other attacks were to follow including those on Udhampur and the Air Force base in Pathankot. Pakistan called India's bluff then as now.

In response to the recent outrage at Uri, India's leadership announced that it planned to diplomatically isolate Pakistan in an effort to pressure it to relent in its deployment of terrorists to secure the army's foreign policy objectives. Unfortunately, this gambit is doomed to fail if history offers any useful heuristics. Between 1990 and September 2001, Pakistan was thoroughly isolated and smothered with multiple layers of sanctions related to its nuclear weapons programme as well as General Musharraf's 1999 coup. These penalties were in addition to entity-specific sanctions pertaining to the violations of the Missile Technology Control Regime perpetrated by Pakistan and China. However, it was during this precise period that Pakistan was running a sanguinary civil war in Afghanistan, winding down its extensive support of Sikh terrorists in Indian Punjab, while simultaneously widening and deepening its involvement in appropriating the previously indigenous uprising in Kashmir. If Pakistan could simultaneously engage in such profound and diverse sub-conventional activities during a period of deep isolation, what makes New Delhi think that its proposed efforts to diplomatically isolate Pakistan today will coerce Pakistan to abjure its well-honed use of Islamist terrorism?

Unfortunately, the only way to make Pakistan cease its trafficking in death for political aims is to significantly alter Rawalpindi's cost-benefit analysis. There are two components to this strategy: first, reducing the benefits it enjoys from the same, and second, raising the costs of terrorism.

To reduce the benefits that accrue from the strategy, one must understand what those benefits Pakistan derives from attacks on India are. After any such attack, peace-mongers in India and beyond renew their bleating for 'dialogue'. One engages in dialogue with a party that wants peace. However, there is no evidence whatsoever that Pakistan's deep state wants peace. One should be very clear: Pakistan's deep state is the only state that matters in this game. Any civilian overture towards India has been consistently undermined by the deep state because peace is literally a threat to the deep state's deeper interests. If there were ever to be some modicum of peace, how can the army justify running and ruining the state per its own whim? It could not.

Indians and the rest of the world must understand that the Pakistan army will always be a spoiler of even the most well-intended peace overture from Pakistan's beleaguered and besieged civilians. Once one realises this, one must confront the very real question of the ultimate aim of this dialogue because it cannot produce peace. Worse, any dialogue with Pakistan on 'outstanding disputes' rewards Pakistan by reaffirming the deep state's contention to its yoked citizens and wearied international community that there is, in fact, a territorial dispute.

In fact, there is no territorial dispute in which Pakistan has any defensible equities. Neither the Indian Independence Act of 1947 nor the Radcliffe Boundary Commission accord Pakistan any claim to Kashmir. The Indian Independence Act of 1947 averred that the sovereigns of princely states could choose which state to join. As is well-known, Maharaja of Kashmir Hari Singh only acceded to India after Pakistan dispatched irregular forces to seize the terrain by force. In fact, Pakistan makes this claim based upon the Two Nation Theory, its communally bigoted founding ideology.

Pakistan will not change course until it faces serious political, diplomatic and military costs for its malfeasance. Politically and diplomatically, India may consider putting its partners to the test by resisting international pressure to engage Pakistan for the sake of optics. The US State Department's statement on Uri mercifully avoids the language of 'dialogue' which plagued past crises and rewarded Pakistan by equating the perpetrator (Pakistan) with the victim (India). President Obama, at the United Nations General Assembly, asked those nations engaged in 'proxy wars' to end them. But he stopped short of naming Pakistan. While American official demurrals from mentioning Pakistan as the likely culprit may have been a prudent act in the absence of more facts, as evidence emerges, the United States should specifically name and shame Pakistan. India would also be behooved to abandon its efforts to raise the issue of Balochistan— no matter how just the move is—because it gives the impression that India and Pakistan are in a tit-for-tat diplomatic scrimmage at the United Nations. This undermines India's credibility on this issue and undermines India's moral high ground on the specific issues of Pakistan's malfeasance in India. India likely doesn't want to set a precedent of commenting upon a neighbour's internal security challenges when its neighbours may reciprocate the favour.

Instead, India would be better served by fixing a laser-like focus upon Pakistan's support for terrorist organisations in international fora, and galvanising the emergence of an international consensus in support of India's position. China will likely rebuff any move to designate Pakistan's beloved proxies because China is Pakistan's surrogate at the United Nations Security Council. But even China is growing increasingly languorous with taking the heat for Pakistan's imprudence. Continued pressure at the United Nations will force China to either continue defending the indefensible or relent to new designations.

Short of war, India has other options. First, India may consider declaring Pakistan a state sponsor of terrorism. Why should the US and the EU monopolise the power to name and shame? Arguably if India wants other capitals to do this, it should lead by example. Delhi can revoke Pakistan's 'Most Favoured Nation' status. While the financial penalty will be relatively small, the diplomatic significance may be notable. India can downgrade the status of the Pakistan High Commission and its own embassy in Islamabad. It can oust the ambassador as well as the ISI chief in Delhi, who is the defence attaché. While these characters will be replaced by other cogs, the signal will be sent.

There has been discussion of reneging from the Indus Water Treaty. While this sounds like an act short of declaring war, in fact, it will be an opening salvo in a likely conflict as this will threaten Pakistan's core interest: the survival of the state itself. Moreover, India will likely draw international opprobrium as such a move will harm ordinary Pakistanis as well as the deep state. Instead India may evaluate options on the lower end of the conflict spectrum. There is surprisingly little public debate about sub- conventional deterrence. After all, if nuclear weapons provide Pakistan with immunity for its follies, don't India's own nuclear weapons afford India the same impunity? There are numerous fault lines that India could exploit if it were willing to forgo its aversion to such actions.

Limited air strikes from Indian airspace on Pakistani camps with precision-guided munitions may be an option. However, Pakistan has competent air defences and may well shoot down Indian aircraft flying sorties in its own airspace. India will need to be prepared for escalation. India should make it clear to the US and the international community that its press-ganging is best served by pressing Pakistan to accept loss of terrorist camps as a price of terrorism. To date, Pakistan has relied upon the international community pressing India to de-escalate. This only further shields Pakistan from the consequences of its own actions. This equation must change if the international community wants less instability in the region.

Over the longer run, India may be well-served by dusting off some variant of 'Cold Start'. Pakistan can brandish threats to use its battlefield nuclear weapons. However, simple math reveals that Pakistan's threats are hollow. India will survive any nuclear exchange despite grievous loss of life and damage to key cities. Pakistan will cease to exist as a political entity in its current form. Moreover, India is not likely to be left responding to Pakistan's first use on its own.

Foes of developing more offensive means to compel Pakistan to kick the terrorist habit argue that it's a good time to be an Indian. Economic growth has been solid even when the rest of the world was suffering a severe retraction. This growth can continue if India can avoid a protracted conflict with Pakistan. This policy of strategic restraint assumes that some number of Indians will die. And this may well be a reasonable, if calculatedly cruel, trade off. However, if the intent is to coerce Pakistan to exit the jihad game, neither diplomatic isolation nor strategic restraint will fit the bill.

The international community should stand by India in any decision it makes. After all, it—particularly the US—has contributed to making Pakistan the menace it is.