An Exceptional Tryst

INDEPENDENCE DAY IN INDIA has a powerful emotional content, but it is Republic Day which has greater fanfare. This is quite unique for, rarely in modern Europe, where Republicanism and Nationalism began, are the two granted equal respect. If in India we accord both due recognition, though the festivities are different, there is good reason for that.

Indians, doubtlessly celebrated Independence in 1947 with great enthusiasm but this joy was mingled with sorrow for we were still burdened by two pressing concerns. The first was the bloody Partition and, though we kept our "tryst with destiny", it caused a lot of pain to cut one body into two. It was midnight then but also the high noon of a mass tragedy.

Second, India's independence movement was very unusual for our leaders had more than ousting the British on their minds. From the 1920s, if not earlier, social reform played an important role in shaping our freedom struggle. This aspect surfaced from time to time, whether in terms of uplift of castes or policies towards minorities and women.

When we finally won our freedom, we were also aware that there "were miles to go" before we could rest. While India was getting ready for severing its ties with the British, she was not just settling post-Partition refugees but also deep in contemplation about fashioning a Republic. Our leaders were clear: Independence without a democratic constitution would be incomplete.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Such twin concerns did not occupy Europe in the mid-19th century. In Italy, France, Norway, and Germany, the most important national day is when the republican movement triumphed over monarchy and asserted individual rights.

In textbook European conditions, the republican spirit of freedom from traditional authority came well before nationalism.

This is why secularism, from the start, was not just about the separation of church from the state. It also firmly opposed absolutist monarchies, which may well have been irreligious, because they did not allow other points of view to flourish. It is this that forced many erstwhile rulers to eat humble pie and heed popular opinion.

With a slight twist, this applies to Belgium as well. When King Leopold was placed as head of state, he wholesomely acquiesced to be bound by a republican constitution. Norway, perhaps, represents the other extreme for here there is an explicit recognition of the Constitution Day which overshadows memories of the country's independence from Sweden.

A quick recount of 19th-century western European history might help. Britain is often touted as a perfect example, but the lesson from popular upsurges from France to Spain around 1848 is illustrative. These years were called the "Spring time of the Peoples". Its famed participants, the legendary "Forty-Eighters", were all high on democratic rights.

This aspect characterised more than the Paris uprisings; it also brought about the unification of Italy and Germany, and led to Louis Philippe's abdication. Europe was flush with such mobilisations, and in each case democracy was the standard bearer of these popular upheavals. The fight against monarchy in Europe preceded the emergence of nationalism there.

Consequently, the boundaries of modern European nation-states and old empires do not coincide. It is also forgotten that nations in Europe, when they came into being, did not make concessions to cultural differences, including those of language. India, as we know, made room for diversity from the very beginning, even during the independence movement.

At any rate, the national day in most of Western Europe is when republicanism was born and not when independent nation-states came into being. In such democracies there is a powerful emphasis on individual rights, to the extent of making sure that the state is constrained by negative laws. Where independence leads the charge, the state is more benignly envisaged.

This is why rarely in Europe is the birth of a nation and a republican constitution celebrated; it is either one or the other, usually the latter. As republicanism came first, it tends to undermine the significance of a national day. India does not fit this mould because we have good reason, as we saw earlier, to honour both these events, but they are done differently.

Except for Finland which became independent of Russian control in 1917 with the Bolshevik Revolution, independence is not of much consequence in that part of the world. This is not surprising as France, Britain, Germany, Belgium and Spain were all colonial powers and it is independence from these imperial forces that countries like India celebrate.

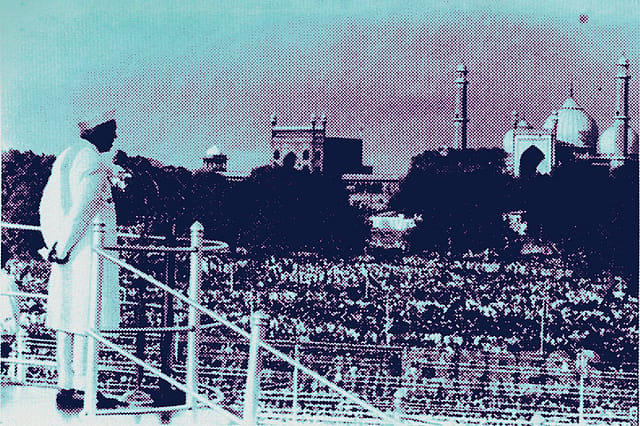

In India, the major attraction of Independence Day is the prime minister's speech from the Red Fort. This is not just for the televised audience but is addressed to diplomats, dignitaries and school children as well. This is a much more sombre occasion than our Republic Day when drums, march pasts, tanks and cultural floats roll out and planes spew colourful plumes above.

Independence Day was, from the very beginning, not simply jubilation but also burdened by responsibility to "wipe every tear from every eye." Normally, a birth is not welcomed in this fashion but with good cheer and festoons; yet India's independence had all that plus the recognition that much remained to be done. India made a promise that day to the nation.

This is why our "tryst with destiny" had a remainder. We had but managed to "redeem our pledge, not wholly or in full measure, but very substantially." It was as if, at that moment of exuberance, our leaders knew that the drawing board was still out there for our Constitution to be framed. Accomplishing this task would help us "redeem our pledge"; this time fully.

National independence generates a sense of patriotism but not always republicanism at the same time. At such historical moments there is also an enemy, an outsider, that needs to go so that "the soul of the nation, long suppressed, finds utterance." But the Indian soul needed much more than freedom and our first Independence Day brought that aspect out vividly.

In all subsequent prime ministerial speeches, August 15 is the day when there is a recounting of that pledge in different words, with different numbers and different programmes. These are recalled to either mark as achievements or chalk up as work yet to be accomplished. Freedom from colonial rule was done and dusted, now let us move ahead.

Ironically, on August 15, 1947, when Nehru was delivering his famous Independence Day speech, Mahatma Gandhi was doing his best to "redeem pledges" made to the Indian people. He was not in Delhi, or in some other happy gathering, but in West Bengal, doing his best to quell the deadly Hindu-Muslim riots that marred that region. That was the Mahatma's pledge.

From"tryst with destiny" to invocations of"Amrit Kaal", Independence Day always enlivens a much larger symbolic resonance for us in India. It is more than just freedom or quashing of external threats. In fact, every year on August 15, no matter who our prime minister is, the bulk of the message from the Red Fort's ramparts is to deliver progress.

India is quite unique in another respect as well. Unlike all other constitutions, our republican Constitution places the importance of 'fraternity' in the very first sentence. This does not happen even in the French constitution. If one were to study the Independence Day speeches of our prime ministers, the need and urgency of establishing fraternity is in every one of them.

Our success in establishing 'fraternity' may be debated, but it occupies a pride of place in our Constitution. It shall always remain an agenda item on which India can expect a periodic Action Taken Report. It was recognised that liberty and equality were easier to deliver than fraternity and that is what kept Gandhiji engaged in West Bengal on August 15, 1947.

When India became independent our leaders had also to prove to the world, and to naysayers within, that they were not "men of straw" and India was a durable and legitimate nation-state. In the early post-independence years there were some who belittled our anti-colonial struggle and deemed our freedom from colonialism as an eyewash, even a "lie".

Then there were others who saw the freedom of India as a freedom of north India alone. It took several years before such fears were put to rest. Later, when the demand for unilingual states came up, once again there were tremors across the country. Many wondered if this was the beginning of the end for India as a coherent, unified nation-state.

Such apprehensions failed to take into account that India's freedom movement had a much larger ideological component that embraced all of India as a precondition. It was not as if getting rid of British colonialism was a one-point item for our independence leaders. This is why, even when India faced severe internal challenges post-1947, it still held firm.

For this reason, India could conceive of linguistic states and not fear a balkanisation of the country. At this point we should recall that the idea of unilingual states in a federation-like entity called India was envisaged in the 1920s. This, at a time when independence was still far away. It also explains why our post-1947 trajectory was not an abrupt departure from the past.

TO GET A MEASURE of the significance of this, let us contrast our situation with that of Sri Lanka. After some initial hesitation, much of India began to be administered on the basis of unilingual states.

This development did not break up the country, nor undermine democracy but, in fact, strengthened both. At first there were some apprehensions, but they soon died.

Contrarily, in Sri Lanka, no allowance was made to linguistic diversity nor to the promotion of the sentiment of being one, over and above cultural variations. Consequently, Sri Lanka paid heavily in its post-independence years with protracted civil wars; a fate we were completely spared. Those who undermined India establishing unilingual states should remember this.

It is quite remarkable how India's independence struggle remained united in spite of the many languages and creedsinthesubcontinent. Whatmostcommentatorsearlier overlooked was that India was fighting for more than independence. Fromstarttofinish, thequestwasforarightful place in the sun as a self-respecting and proud nation.

This kept our India from being balkanised as a large number of experts had predicted. Unbelievably, the country stood as one, and this was primarily because of the promise of the Republic which gave us the instruments to pull together, united. As a result, rather than cultural flattening, or discord, we saw cultural efflorescence without domination.

The making of unilingual states did not result in further fragmentation of the country but, in fact, strengthened it. When the cry for Maharashtra, Gujarat, Punjab, Haryana, and Andhra Pradesh came up there was a smugness of an "I-told-you-so" variety among a host of experts. They believed that unilingual states would soon doom India as one country.

Instead, what happened was surprising. Once these unilingual states were formed their leaders immediately declared that their job was over. The fear that unilingual states would inevitably fragment India and bring her down on her knees did not happen. For example, Bombay state became Maharashtra and Gujarat and once that happened, they both grew apace.

Whatever trepidation existed when the demand for unilingual states was first expressed, disappeared by the time Uttarakhand, Jharkhand or Telangana came up. It's worth noting that the formation of these states was initiated by the governments of the day and not by mass pressure from outside. Clearly, by then India had become supremely confident of herself.

To even remotely fear that our unity and independence are internally threatened today betrays a misunderstanding of the exceptional features that made India so special on August 15, 1947. If there are internal enemies, they are overwhelmed by those who swear by a united India. This is the contribution of the many brave men and women who made our independence so unique.

Additionally, our freedom movement was non-violent, in the main, and for this we must pay homage to Mahatma Gandhi. Yes, there were trying times, as in Chauri Chaura, when many senior Congress people were miffed by the sudden withdrawal of the non-cooperation movement. In retrospect, this was the first, inaugural step that kept us democratic post-1947.

This achievement was certainly quite unique, especially among the newly independent countries that came into being after World War II. It is not as if national movement always ends with democracy, most do not; for example, look at our immediate neighbours. The forces propelling independence and those of democracy are separate, in India they combined as one.

This happened because non-violence was the central credo of the freedom movement. No matter how well-intentioned, once violence enters the frame, there is always the temptation to short-circuit discussion and deliberations in favour of a quick solution. Violence appears an attractive option at first but its ugly side, which may have been unanticipated, soon shows up.

If violence, however lofty and patriotic in tone, becomes the major propulsion behind an independence movement, it gets difficult to later veer the state towards democracy. The discipline needed to respect (not just tolerate) others who think and live differently is hard to instil as it demands a deliberate quietening of instant, primordial passions.

We, in India, were lucky that Mahatma Gandhi emerged as our primary symbol of independence even though he had his share of detractors. The one thing that democracy should teach us is that when violence seems to be the only option, we have not given reason a chance. We raise our voices and strike in anger only when we are losing an argument.

The 'charkha' appropriately became a powerful symbol in the hands of one man, MahatmaGandhi.

The charkha is often incorrectly seen as a concession to anti-industrial and anti-developmental ideologies. A visit to Sabarmati Ashram, even after so many years, still enlivens the 'charkha' as our symbol of defiance; a slingshot against the mighty Goliath.

For us, Independence Day remains solemn for we had a companion event to inaugurate, which we did three years later on January 26, 1950. This is why the celebrations, the festoons, the parade and marches are reserved for another day and not August 15. Pakistan may have been India's twin, separated at birth, but grew up to be an entirely different country.

This is yet another paradigmatic example of culture trumping nature. While India fought against the British and all they represented, Pakistan's national day is against India and the fear of Hindu domination. March 23, 1940 was when the Muslim League passed the Lahore Resolution whose primary purpose was to carve a separate land for the Muslims of India.

This day then became the national day of Pakistan, forgetting that Hindus and Muslims of undivided India were under the British yoke for centuries. While we look at Partition as a mass tragedy of the kind that the world has seldom seen, for Pakistan it is different. They see Partition as a celebration of a promise long ingrained in the psyche of Muslims in India.

NO WONDER, PAKISTAN HAS fumbled through three constitutions, all lacklustre and moribund from the start. Military rule has characterised Pakistan and even when there is a nominal civilian state, the power is always with the army. While in India the Constitution was the companion volume of Independence, Pakistan thought of the gun and not the pen.

Non-violence also gave wing to our bid to stay non-aligned and away from the competitive demands of the superpowers. In hindsight, it is rather easy to criticise this step on the part of the Indian government, but a quick look at where Pakistan's SEATO and CENTO military alliances have left it should tell us that our early leaders did get a few things right.

Imagine a country coming out of foreign rule and then quickly lining up behind another; whether the US, the UK or the Soviet Union. If it were simply getting rid of the British, then such military compacts with other nations may have made sense. However, as our independence carried the promise of delivering development to our own people first, we could not belittle that freedom.

In hindsight, one may find fault with this dogged insistence on staying free from international alliances, but such a stance was a further demonstration of our independence. Why should our freedom years be ruled by the warring instincts of others? After all, political energy is limited, so wisdom lies in thinking about our advances first before serving external alliances.

In India we recognised that independence was necessary, not just as a cultural assertion but also to lift India from poverty and disease and wipe away every tear. Aligning with superpowers would take our attention away from our own needs and place the security demands of others alongside, if not ahead.

The scenario obviously changes once we are strong enough to resist other powers and can bargain with them on our own terms. Imagine, in 1947, we had nothing of our own; except for what the British had done, and that too primarily for their colonial interests. Our literacy rate, our infant mortality rate, our grain and industrial output, they all stagnated at low levels.

When we examine the huge advances we have since made on these fronts, it is clear that none of these would have happened without the promise of the Republic in our independence. Intellectually, India leaped forward and we embarked on our very own industrial revolution. We had the brains to back up our brawn, and were not leaning on foreign experts.

This is why when we celebrate Independence Day we must remember our promises to the future generations and not just exult in our political freedom from past tormentors. Many countries that became independent after World War II did not think of the rules they would follow in future to develop and that is why they stayed undeveloped and undemocratic.

Hence, no matter who our prime minister is, on Independence Day they all remember our national leaders with gratitude, regardless of party affiliations. India has reinvented both patriotism and nationalism by infusing it from the start with the republican spirit that other new states, most often, never manage to capture.

Our independence movement was, indeed, exceptional, which is why we gratefully acknowledge it every year on August 15.