TOM STOPPARD, THE British playwright, is perhaps the greatest living playwright of our time. He was born in Zlin, of Jewish parents, in what is today the Czech Republic. His birth name was Tomá Sträussler. In 1942, when he was five years old and with war raging in Europe, he found himself in Darjeeling.

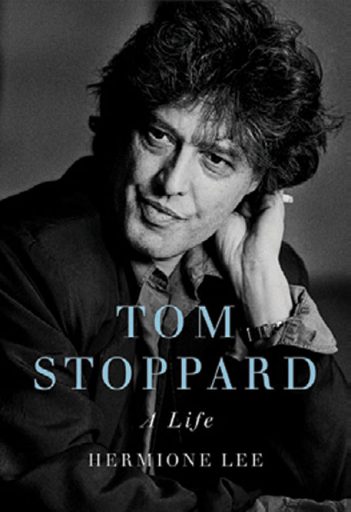

It is a long story, told by Hermione Lee in his biography Tom Stoppard: A Life. The book is the size of a brick, almost a thousand pages thick. It can be heavy going at times but the famous playwright’s four years in India and how Tomá Sträussler became Tom Stoppard makes fascinating reading.

Zlin was a small company town with the Bata shoe factory providing most of the employment. Tom’s father Eugen Sträussler was a company doctor. When Germany invaded Czechoslovakia in 1939, all the Jews who were able to do so left the country in haste. Most of those who remained behind perished in concentration camps.

Eighty years ago, Bata was the largest shoe company in the world, with thousands of branches all over the world. In the US alone, there were 300 Bata shops. Eugen Sträussler, his wife Marta and two children, Petr and Tomá, were given the choice of escaping to either Kenya or Singapore. Other Jewish employees were given other choices—Canada, the US and Argentina, for instance.

Bata was founded in 1894 by a family of cobblers. It came to India in 1931 and set up operations in Konnagar near Calcutta. It soon established the factory town of Batanagar in 1934 near Calcutta. The company’s fortunes went downhill after World War II when it was nationalised at its headquarters after the communists took over Czechoslovakia. Today, what is left of Bata is operated out of Lausanne in Switzerland.

Between Kenya and Singapore, the family chose Singapore. It was a big mistake. In early 1942, three years after they arrived, the Japanese army advanced on the city. The British evacuated the women and children first and the Sträusslers were put on board a crowded ship bound for Colombo. The father was left behind with other men. From there they were transferred on another ship, which the mother thought was heading for Australia.

Instead, it sailed West and Marta and the boys, aged six and four, arrived in Bombay on February 14th, 1942. The mother wept. Their entire lives were shaped by this misunderstanding and a random act of fate. When he became famous in the 1960s and the interviewers asked Stoppard about his past, he said he was a “bounced Czech”.

The family never saw the father again. In all likelihood, Eugen Sträussler was on a ship that was heading for Australia and was bombed and sunk by the Japanese near Sumatra.

The mother’s resilience was remarkable. After disembarking in Bombay, they moved across India six or seven times. Stoppard’s 1995 play, Indian Ink, though set in the 1930s, is based on those nomadic days in the backdrop of a country seeking independence.

Bata looked after its own. It had branches across India. In the first winter, the family went to Nainital and then to Lahore, which they found “dusty, wretched and full of flies and mosquitos”. They returned to Nainital and shared a big house with other Czech wives and children. They did not always get along but ate together in a canteen.

Petr and Tomá went as boarders to a convent school, St Mary’s, where they learnt to speak and write in English. After a year, the family moved to Darjeeling where the Bata shop needed a manager. Marta’s bookkeeping was poor and the staff probably took advantage of this, but the Nepali salesman was helpful and his wife knitted woollies for the boys. The shop was well located, in the centre of the town, next to the Keventer’s Milk Bar.

In the early 1940s, Darjeeling was heaving with British and American soldiers. They stayed in hotels like Mount Everest and frequented the Gymkhana Club, the Chinese restaurants and the Capitol Cinema that was next to the shop where young Tom bought his copies of the children’s magazine Beano.

Darjeeling had a number of public schools, the most famous of which was St Paul’s, but the family could not afford it and the Sträussler boys were sent to the less grand co-educational Mount Hermon, run by American missionaries. They were boarders.

Tom got besotted with the daughter of the school’s matron. Years later, when he became famous, he received a letter from her asking if he remembered her. “Not only do I remember you,” he wrote back, “I was madly in love with you.” He never heard from her again.

Most weekends, the mother would visit them bringing with her food parcels and treats. They would sit waiting for her on a bench under a grand fir tree and would run to meet her when they saw her coming. Both boys did well in school. Tom liked books and, at one time, he had a fantasy of opening a bookstore to rival the Oxford Book Store on Chowrasta in Darjeeling. He remembers those days as one of “uninterrupted happiness”.

‘Very often’, Stoppard wrote, returning to the place in 1991, ‘a belt of mist lifts the mountains off the earth. They float in the sky, infinitely far off and yet sharply detailed, massive yet ethereal, lit like theatre, so ageless and permanent as to make history trivial. It is perhaps the most mesmerising view of the earth from anywhere on the earth’

Share this on

The mother was an attractive young widow in her thirties. She was invited to a dinner at Mount Everest Hotel where she met Major Kenneth Stoppard who was based in New Delhi and was on leave in Darjeeling for a fortnight. He started turning up at the Bata shop every day and bombarded her with flowers and chocolates. Then he shuttled back and forth between New Delhi and Darjeeling. The major was a handsome clean-cut Englishman from Nottinghamshire.

He sent her a telegram proposing marriage. Without telling her children, Marta travelled to Calcutta and married Major Stoppard in St Andrew’s Church on November 25th, 1945. For years, she felt guilty about not telling the boys in advance.

The Stoppards left India the following year. They stayed at the army transit camp at Deolali before departing from Bombay on a British troopship. Marta, who was 35, became Bobby; Petr, now 10 years old, became Peter; and Tomas, eight, became Tom. They took the stepfather’s surname.

From the Mall in Darjeeling there is a view of one of the world’s highest mountains, Kanchenjunga, with the Himalayan range stretching out on its both sides.

“Very often”, Stoppard wrote, returning to the place in 1991, “a belt of mist lifts the mountains off the earth. They float in the sky, infinitely far off and yet sharply detailed, massive yet ethereal, lit like theatre, so ageless and permanent as to make history trivial. It is perhaps the most mesmerising view of the earth from anywhere on the earth.”

Postscript: Felicity Kendal is a successful television and stage actor in Britain. In the 1980s and 1990s, she had leading roles in many of Tom Stoppards’ plays—The Real Thing, Hapgood, Arcadia, Jumpers and in Indian Ink that he had

written especially for her.

When she was acting in one of the plays, she and Stoppard—both married, both parents and both famous names—embarked on an affair that lasted 10 years.

Felicity too had spent her childhood in India. Her parents, Geoffrey and Laura Kendal, ran a touring theatre company that put on classical dramas—Shakespeare, Shaw—before a Maharaja one day and in a school in the hills the next. Shashi Kapoor was married to Felicity’s older sister, Jennifer.

About The Author

Bhaichand Patel is a former director of the United Nations. His most recent novel is Across the River

More Columns

The US$4 Trillion Monopoly Madhavankutty Pillai

Elite Socialism vs. Old Fashioned American Hustle: New York’s Mayoral Showdown Vikram Zutshi

From Manipur to Global Glory: John Gwite rides 3,600 km to set new Indian record at World Ultra-Cycling Championships Open