The NRC and Assam’s Deliverance

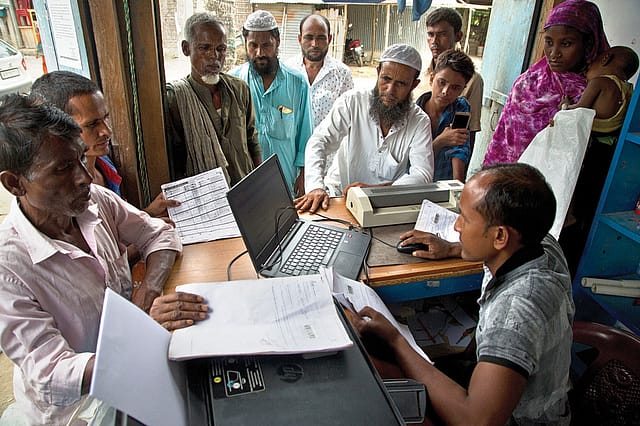

THE FINAL LIST of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) was published in Assam on August 31st. A little more than 31 million of the approximately 33 million applicants found their names in the NRC. The 1.9 million excluded also include those who did not submit their claims. These three figures, seemingly innocuous, have not been able to keep at bay the politics of disappointment, outrage and we-told-you-so. Advocates and opponents are all unhappy with the outcome —whether the excluded are too many or too few, whether many genuine citizens have been left out and many more foreigners accommodated —of an exercise that has been as enormous for the state as Aadhaar enrolment was for the nation, in terms of logistics. The evidently bungled process has forced the Assam government's decision to approach the Supreme Court for a re-verification of the list. But this failure doesn't take away from the socio-political significance of the NRC as an emotive demographic and democratic struggle for the people of Assam. This is still not adequately comprehended in India's distant metropolises—distant from the Northeast lying beyond the geographical and psychological warp of the 'chicken's neck' in northern West Bengal—often owing to a wilful blindness.

Behind Assam's emotional investment in the NRC is also an economic reality which would explain why support for updating the list has been overwhelming and uniform across the state. In simple terms, the question is who can rightfully lay claim to precious and finite resources, some of which, such as land, is not only premium but also worth every generation's struggle to acquire and utilise in Assam, given its fertility. When there is a dispute, and one spanning socio-ethnic divides, it is reasonable to assume that the state has a role to play in sorting things out. The first step then must be ascertaining whose claim is weightier—and it is not unreasonable to believe that the claims of some may be found to be more legitimate than those of others. The NRC exercise, from this perspective, is nothing more than doing just the above by digging into genealogy. Thus, it has always come as a surprise to the Assamese that their struggle gets defined as an attempt to exclude members of a particular religious community from citizenship.

Openomics 2026: Continuity and Conviction

06 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 57

The performance state at its peak

Assam, with its history of being undivided and divided Bengal's neighbour, with a language phonetically very close to Bengali and sharing the same script with variations, has been paying the price of periodic changes to its status and contours and the coming and going of districts and sub-regions. In February 1874, the then Greater Sylhet region was added to an expanded Assam, notwithstanding protests from its Bengali population. Sylhet returned to Bengal after the 1905 partition of Bengal when the province of Eastern Bengal and Assam was constituted. Sylhet departed from Bengal again seven years later when Assam was reconstituted once more. Finally, the July 1947 Sylhet Referendum saw the region join East Pakistan, but leaving behind the fertile Barak valley in India. Assam was quite happy to let Sylhet go in 1947, thinking it would ease linguistic and religious tensions. But Assam was evidently counting its chickens. Although the state got smaller post-Independence, this border with Sylhet and the two districts of Karimganj and Cachar at its southern (and eastern) point of contact with Bangladesh and the current districts of Dhubri and South Salmara Mankachar at its northern (and western) point of contact would remain its Achilles heel.

Assam became a varied and violent geography of identity conflicts. Not all of it had to do with illegal immigrants, but the districts bordering Bangladesh came to set the terms of the conflict more and more. The claim of illegal immigration has less to do with 1947 and 1971 (the cut-off date of March 24th, 1971 was the eve of the Pakistani military's commencement of Operation Searchlight that led to the East Pakistan genocide and a fresh flood of refugees to India) than with the continuous influx through the 1980s and beyond which is attested to by both ordinary civilians and officials on the ground. The imperative of the NRC can be understood only in this context.

The tragedy of the NRC is that the question of rights came to be monochromatically explained as one of 'human rights' pertaining only to those who could be left out. This coloured the discourse in the 'mainland' west of the chicken's neck. What was ignored was the decades-long protestations of the Assamese that illegal immigration is a fact, that periodically entire villages were almost overnight taken over by people not there earlier and that the resulting demographic change soon impacted politics. Unfortunately for Assam's NRC enthusiasts, the Nellie massacre of 1983 had ensured, among other things, that only one narrative—that the demand for a register of citizens was merely a mix of xenophobia, ethnic chauvinism and sectarianism—was mainstreamed while the other, including stories of people being driven out of their homes, by alleged Bangladeshis, in areas where they otherwise were not dominant (for example, as happened with the Bodos in Morigaon), was buried.

Concerns about what happens to those left out of the NRC are legitimate, especially when genuine citizens may have been excluded. Whether those undoubtedly non-citizens can be repatriated to Bangladesh—with Dhaka run by its India-friendliest government ever, it is a rather delicate challenge—or accommodated elsewhere is another matter. But in the debate, very few have asked how a democratic state can call itself sovereign when it cannot ensure that the right to vote is not made a travesty of. Nothing makes a bigger mockery of a state's sovereignty than non-citizens voting to determine who runs it. If there is a humanitarian and political tragedy here it is not that the NRC has been updated, however ham-handedly, but that successive governments had neglected to do so. This, in turn, allowed the arithmetic of identity politics and identity-based voting behaviour to not only persist but also repackage itself in the garb of human rights and fear of disenfranchisement when the NRC became news again.

The NRC has been updated under the Supreme Court's supervision, without the involvement of the Central and state governments in the actual process. The laws that define citizenship criteria pertain to all religious communities, and do not name any. The two lists of acceptable documents are fairly exhaustive—and lack of documentation is a problem that affected people in some remote and Tribal areas too. Since these people are not Muslims, the argument that the entire NRC exercise was designed, or misused, to target Muslims seems to be little more than fear-mongering. On the other hand, the apex court's admonitions, asking why the NRC authorities had allowed the resubmission of documents—this had opened the door to alterations to already submitted genealogies—have been conveniently forgotten.

Citizenship in Assam needs to be defined by documentary evidence because the state has historically been indolent when it came to maintaining and updating land records. This is complicated by illegal immigration. If it is a moral imperative that democracy trump demography, the Assamese saw themselves losing out in terms of both. They came to see the 2016 Assembly election as their last chance—that backing for the NRC from a numerically secure Central Government was an opportunity they could not waste, and were unlikely to get again. Almost 35 years after it was signed, the Assam Accord of 1985 may yet begin delivering on its promises if the NRC can be fixed. Incidentally, a significant achievement of this exercise is overwriting Assam's history of secessionism, tying Assamese aspirations firmly to Indian nationalism, and the state's security to national security.