Testament of the Wonderstruck

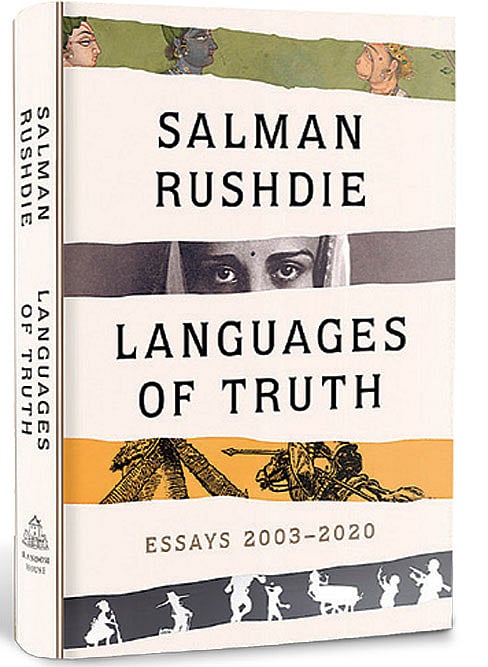

YOU ARE WHAT the story makes you. And some of you tell stories that seek their ancestry in your own private One Thousand Nights and One Night still lingering somewhere in the farthest province of memory—art is always indebted. It’s the eternity of echoes that turns every story into an existential definition. And that’s how Salman Rushdie traces the origins of words that make up his fictional world in the ‘Who Am I?’ sort of introduction to his new collection of essays, Languages of Truth (Hamish Hamilton, 368 pages, Rs 799) written between 2003 and 2020. What he calls the wonder tale, whose migratory power defies borders and cultures, is the progenitor of fiction, or at least the kind of fiction he writes with defiant steadfastness in the face of increasing critical hostility. From the most epical of the epics, The Ramayana, to the pared-down delight of Amar Chitra Katha, the trajectory of the wonder tale parallels the evolution of ‘imagined’ storytelling itself. “The great migration of narrative has inspired much of the world’s literature, all the way down to the magic realism of South American fabulists, so that when I, in my turn, used some of those devices, I had the feeling of closing a circle and bringing that story tradition all the way back home to the country in which it began.” At the core of this collection is a testament of a writer who continues to be enchanted by wonder tales that are an affirmation and a celebration of imagination.

Which reveals the creative distance he keeps from the currently fashionable memoirists of the quotidian, or from the Knausgaard school of fiction. The non-fictional fiction is in vogue, and in which the autobiographical is the only story worth telling. What matters is not the wonderment but the placid predictability, and the little ripples, of everyday. Rushdie travels in another world, the one inhabited by Scheherazade, Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy, Bulgakov’s devil, Günter Grass’ Oskar and other such enchanters. “The literature of the fantastic is not genre fiction but, in its own way, as realistic as naturalistic fiction; it just comes into the real through a different door.” The door opens to reveal to the traveller the truth of being astonished by the possibilities of imagination, by the mythologies born in the inheritance of wonder tales. To comprehend the truth that comes from the rustle of languages, we need to know about the literary ancestry of the truth seeker. In this collection, scattered across the pages are definitions and defences of his art. Maybe he needs to do it more than any other writer of his accomplishment because fame—a private life anatomised in public space—has coloured the reading of his fiction. A media-monitored life can be cruel to the imagination. In his own words: “Too much of my life story has found its way into the public domain already; there has been, one could say, altogether too much of the ‘lower gossip’, and for readers of a certain kind it is impossible not to try to ‘decode’ my fiction in terms of what they know, or believe they know, about my own character and private life. This is, I have to say, a little horrifying, and I recoil from it.”

AIming High

20 Feb 2026 - Vol 04 | Issue 59

India joins the Artificial Intelligence revolution with gusto

Autobiography is not a writer’s destiny. But the autobiographical is inevitable; it does affect, in varying degrees, a writer’s sensibility. A bit of Rushdie is there in Saleem Sinai. While writing, he realised the limits of letting himself into the life of the character he was creating: “The author can create character, but once the character has been created, the author is no longer free. He must operate within the limits of the human being he has invented. In short, I had to let Saleem be Saleem and stop trying to make him someone he wasn’t—for example, me.” His declaration of freedom was his character’s too, and he could do it with as much shattering clarity as Saleem’s first cry that changed English fiction in this part of the world because of what he had inherited from the wonder tale. Not just that. He could afford it because of the physical inheritance of multiple migrations—the movement of being in the world. His journeys, within the East and into the West, gave him stories, magical but they carried within them the melancholies of history. That is why the ‘truthfulness’ of his fiction is not ‘truthfully’ told. And that is why he thinks: “If one were in a death-of-the-novel sort of mood, one might conclude that this time of confessional Knausgaardery, this flood of memoir-abilia, and the apparent readiness of readers to turn towards such book with pleasure is not merely a short-term fashion but might in fact soon supplant the subtleties of fiction altogether.”

He finds subtleties elsewhere. In an essay on Gabriel García Márquez, he writes with fanboy excitement about his first discovery, in a bookshop of exotic titles in the mid-seventies London, of the first three sentences of One Hundred Years of Solitude, and years later, courtesy Carlos Fuentes, his trilingual phone conversation with the great teller of wonder tales himself. In Gabo’s pages, he was at home: “I knew García Márquez’s colonels and generals, or at least their Indian and Pakistani counterparts; his bishops were my mullahs; his market streets were my bazaars. His world felt to me like mine, translated into Spanish. It’s little wonder I fell in love with it not for its magic, though, as a writer reared on the fabulous ‘wonder tales’ of the East, that was appealing too, but for its realism.” The Latin American magic, Rushdie instantaneously realised, was as real as the meta-realism of the East he came from. As the cab driver of Cartagena would tell a passing novelist: “Here in the Caribbean we all have great stories. Gabo is just a good typist.” In Rushdie’s non-Knausgaardian universe, it seems, novelists are the chosen styluses of the fabulous, but the fables are not necessarily happy tales. Wonder tales contain sighs and sorrows of lands trampled upon by history, from Macondo to Mumbai.

This collection of lectures and tributes, and populated by friends and icons ranging from Christopher Hitchens to Philip Roth, is united by the idea of freedom and truth in an age of lies institutionalised by politics. The writer returns to the realism of the magic. “The magic of the languages of truth is the only magic in which I believe. And I have to believe, we must all believe, that in the end the truth will set us free.” I can’t help quoting another writer, the least magical of Márquez’s generation from Latin America. In an essay published more than three decades ago, Mario Vargas Llosa wrote: “In effect, novels lie—they can do nothing else—but that is only part of the story. The other part is that, by lying, they express a curious truth that can only be expressed in a furtive and veiled fashion, disguised as something that is not.” As in the truth wrapped in the wonderment of Rushdie’s imagination. Languages of Truth is a smart explanation of his art and cultural attitude that most of his critics have failed to provide.